WR PDF

Preview WR

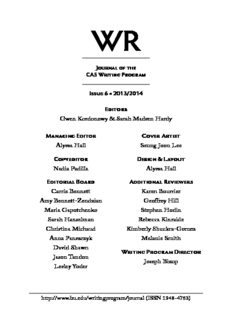

WR Journal of the CAS Writing Program Issue 6 ■ 2013/2014 Editors Gwen Kordonowy & Sarah Madsen Hardy Managing Editor Cover Artist Alyssa Hall Seung Joon Lee Copyeditor Design & Layout Nadia Padilla Alyssa Hall Editorial Board Additional Reviewers Carrie Bennett Karen Bourrier Amy Bennett-Zendzian Geoffrey Hill Maria Gapotchenko Stephen Hodin Sarah Hanselman Rebecca Kinraide Christina Michaud Kimberly Shuckra-Gomez Anna Panszczyk Melanie Smith David Shawn Writing Program Director Jason Tandon Joseph Bizup Lesley Yoder http://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal (ISSN 1948-4763) Contents Editor’s Note 1 Gwen Kordonowy WR 100 Essays The Dichotomy of Science 4 Patrick Allen What’s Out of Sight Is Not Out of Mind: Psychoanalysis and Sound in The Sopranos 14 Morgan Barry The Artist is Present and the Emotions are Real: Time, Vulnerability, and Gender in Marina Abramovic’s Performance Art 24 Ryan Lader Beyond Beneficence: A Reevaluation of Medical Practices During the Progressive Era 35 Jamie Tam WR 150 Essays Fitting Animal Liberation into Conceptions of American Freedom: A Critique of Peter Singer’s Argument for Preference Utilitarianism 47 Laura Coughlin WR Crossbones: Forensic Osteology of the Whydah Pirates 59 Prize Essay Winner Andrea Foster Eusociality: A Question of Mathematics or Bad Science? 71 Julie Hammond Cross-dressing in Renoir’s La Grande Illusion and Europe’s Wartime Masculinity 80 Prize Essay Winner Thomas Laverriere Borat: Controversial Ethics for Make Better the Future of Documentary Filmmaking 90 Prize Essay Winner Hannah Pangrcic Making Sense: Decoding Gertrude Stein 102 Carly Sitrin That Ayn’t Rand: The Sensationalization of Objectivist Theory 114 Nicholas Supple Honorable Mentions 124 Editor’s Note When students arrive at the university, they enter in medias res— that is, they confront a multitude of disciplines and discourses with long, complex histories and are asked immediately to participate in pushing them forward. Boston University, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the CAS Writing Program are all charged with helping students become civically minded thinkers who will use the knowledge and experiences they acquire in their undergraduate years to make a difference in their fields and communities. This goal is made immediately apparent to students in their writing classes, in which they must take stock of both inherited traditions and cutting-edge theories and use (and at times revise) these methods in order to interpret past and/or current events, debates, and cultural repre- sentations. Here in Issue 6, in which we’ve published eleven superb essays from a pool of 430, you’ll see how the best writing asks readers to see things differently. In essays written for WR 100, Morgan Barry and Patrick Allen interpret cultural forms we’re familiar with—television, literature and film—in order to get at bigger questions, but they do so in compellingly contrasting ways. In “What’s Out of Sight Is Not Out of Mind,” Barry drills down into a handful of moments in the landmark television series The Sopranos to show us how the soundtrack picks up on the show’s dis- course about psychoanalysis. Conversely, in “The Dichotomy of Science” Allen zooms out, using the figure of the mad scientist to place two time- lines—one literary, one scientific—side by side. Both approaches allow these writers to contribute to and open up interdisciplinary lines of inquiry. Jamie Tam and Ryan Lader also ask us to see things differently, but they 1 WR do so by offering a more complex understanding of context. In “Beyond Beneficence,” Tam lends historical context to our understanding of past medical practices, compelling readers to consider current ethical debates in a similar way. And in “The Artist Is Present and the Emotions Are Real,” Lader provides theoretical context for analyzing a recent piece of per- formance art, showing readers how theoretical engagement can facilitate readings of all sorts of cultural forms, complicating and even overturning our initial assumptions. In WR 150, students continue to put these methods to use, but their essays are enriched with in-depth independent research. Again, the excep- tional student writers whose essays are featured here strive not only to interpret specific evidence persuasively, but also use these interpretations to propel new understandings of the world. In these essays, students are even more active participants in the revision and creation of discourses, making adjustments, filling holes, and even proposing new work to be done. Carly Sitrin writes back to dismissive scholars in “Making Sense: Decoding Gertrude Stein,” addressing a challenging body of work with clarity and purpose; Thomas Laverriere recovers an overlooked theme in “Cross- dressing in Renoir’s La Grande Illusion,” reinvigorating the conversation on an iconic film by bringing recent scholarship to bear in his fresh inter- pretation; and Andrea Foster deploys an alternative genre “Crossbones” to propose a nautical excavation that could have far-reaching implications. While many of the best essays set out to solve problems, others do the work of raising new sets of questions. Nicholas Supple and Laura Coughlin use their research to question the assumptions behind con- temporary political movements. In “That Ayn’t Rand,” Supple responds to the loud voice of a popular political commentator by questioning uses and misuses of major socioeconomic theories, while, in “Fitting Animal Liberation into Conceptions of American Freedom,” Couglin uncovers the root of failed attempts made by animal activist groups in their founda- tional rhetorical approaches. Julie Hammond and Hannah Pangrcic raise questions that are, in a way, about how we raise questions. Hammond’s “Eusociality” worries about questions raised in disciplinary isolation, calling for more collaboration across fields. And Pangrcic’s “Borat” takes a level approach to a highly charged and controversial documentary, raising questions about the very definition of the term. 2 WR Each of these essays has been selected because the writer has taken a risk and followed through with confidence. The essays span disciplines and at times even question disciplinary boundaries. These students arrive in the middle of things, but they write to move us forward—not just for the sake of it, but with a clear sense of purpose, with an eye to the future. — Gwen Kordonowy, Editor 3 From the Instructor This was Patrick Allen’s final paper for a WR 100 course titled “The Mad Scientist in Literature and Film.” In the course, we traced the long history of the mad scientist figure from myths and legends which tell of the religious transgressions of the “overreacher” to more recent stories and their added urgency due to the potentially destructive power of new tech- nologies. We saw that there are many types of mad scientist, whose stories raise different social and philosophical questions, but we found that com- mon themes emerge, especially questions concerning the ethics of research and invention and a consideration of humanity’s place in nature. Patrick made quick progress as a writer over the semester, and this essay demonstrates his increasingly sophisticated vocabulary and sentence structure, and his insightful analyses. Though the scope of the essay is perhaps overly ambitious, there is a logic behind it. He begins with Fran- kenstein, arguably the first major modern mad scientist, who creates a man, then moves to the industrial age with Karel Čapek’s R.U.R., in which men are mass produced, and ends with Dr. Strangelove, of the military- industrial complex, where it is mad politicians and generals who wield the power of technology. Across this line of modern development, Patrick both identifies a type of cultural anxiety that lies behind mad scientist stories, whereby the promise of science can inspire both hope and discontent, and considers what happens when the utopian motives of mad scientists themselves come up against the paradoxes inherent in knowledge, freedom, and, as the word implies, utopia. — Andrew Christensen WR 100: The Mad Scientist in Literature and Film 4 From the Writer “The Dichotomy of Science” is the final product of my work in my WR 100 seminar, “The Mad Scientist in Film and Literature.” The purpose of this paper was to develop an interpretive argument on the topic of mad scientist figures. I at first grappled with settling on a thesis for this project, consider- ing the broad scope of both the prompt and the source material. From Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus to Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, there seemed to be an endless number of directions in which to begin my writing. Should I focus on the hubris of these men and women? Should I argue that they were victims of society’s scorn? These questions proved early roadblocks in my writing process. In order to decide how best to craft a thoughtful argument, I went back to what inspired me to take this course in the first place. Growing up, I loved watching the old black and white movies that breathed life into the pages of Mary Shelley and Robert Louis Stevenson. Seeing the lightning flashes illuminate Doctor Frankenstein’s laboratory in the 1931 Universal Pictures masterpiece or Doctor Jekyll’s first transformation before the mir- ror in Rouben Mamoulian’s film of the same year still amazes me to this day. I chose to take this seminar in order to learn more about these charac- ters with whom I grew up, to delve into their long literary histories which extend much farther back than the silver screen. Over the span of the course, I learned how these mad scientists were truly complex characters. None of them fit the bill for the maniacal madman hell-bent on ruling the world. Rather, I found each of them was caught up in the utopias they envisioned as a result of scientific progress. I thus found the central argument for my final paper. Looking back on this piece, I wonder if I could have made a more convincing argument had I devoted the entirety of the paper to one spe- cific work. I feel I sacrifice depth in my argument in favor of breadth. However, I am nonetheless pleased with my work and I am glad that I can introduce the figure of the mad scientist to a larger audience. — Patrick Allen 5 Patrick Allen The Dichotomy of Science Science has a dual nature. It can uplift and entice us with promises of a better tomorrow, free from disease and tedium, and often follow through with tangible technological and medical improvements. Such a bright future guaranteed by advancement in scientific knowledge can also be a source of anxiety and despair, as it only sheds more harsh light on the dim realities of the present. How, then, does the figure of the mad scientist fit in to this spectrum of science’s influence? The answer: not easily. The mad scientist has served many roles throughout his long literary trajectory, from the swindling alchemist to the misguided father. Such various roles attest to the broad range of meanings which science, in general, can be said to hold. The mad scientist is a caricature of the fear concerning unrestricted learning. However, his image becomes clearer when his own motives are examined alongside his work and creations. Most “mad” scientists are not truly maniacs because they are bent on destruction and world domination, but rather they, too, are caught up in this duality of scientific research. Thus, the appearance and use of the mad scientist symbol, specifically in the works of Mary Shelley, Karel Čapek, and Stanley Kubrick allows for a more nuanced understanding of how the fascinations and apprehensions of humanity are tapped by science, as its approach to a perfect society only makes the distance to such a goal all the more apparent. According to Roslynn Haynes, in her article “The Alchemist in Fiction: The Master Narrative,” the “master narrative concerning science and scientists is about fear—fear of specialized knowledge and the power that knowledge confers on the few, leaving the majority of the popula- tion ignorant and therefore impotent” (5). She suggests that the “typical” 6 WR mad scientist scenario has the deranged megalomaniac threatening the planet and, eventually, failing to follow through with his plans, leading to a “memory of disempowerment” among the general populace to be recalled each time a new scientific breakthrough is achieved. Furthermore, Chris- topher Toumey affirms, “The mad scientist stories of fiction and film are homilies on the evil of science” (1). Thus, Haynes and Toumey argue that fear and suspicion characterize our fascination with science in literature. Yet, fear alone is not enough to sustain some five hundred years of longev- ity enjoyed by the idea of the mad scientist, beginning with the legend of Doctor Faustus. Behind these mad scientist and alchemist figures lies a distinct sense of optimism, which likewise intrigues and captivates audi- ences. Best described by Haynes in From Faust to Strangelove, mad scien- tists, specifically Victor Frankenstein, are “the heirs of Baconian optimism and Enlightenment confidence that everything can ultimately be known and that such knowledge will inevitably be for the good” (94). Indeed, the protagonist of Mary Shelley’s 1818 Gothic masterpiece provides a good starting point from which to launch an examination into how the mad scientist’s work is not solely characterized by vain or arrogant desires, but rather deeply ingrained personal convictions and visions of a better tomor- row. Victor Frankenstein’s fascination with science and subsequent transformation as a result of these pursuits are testaments to the metamor- phic power of science. The young Genovese initially dabbles in scientific investigation with moderation. He reads the works of Paracelsus, Corne- lius Agrippa, and Albertus Magnus, and their writings appeared to him as “treasures known to few beside [himself]” (21). He is fascinated by his foray into the sciences, but he is careful not to throw himself headlong into the venture. He explains: The human being in perfection ought always to preserve a calm and peaceful mind, and never to allow passion or transitory desire to disturb his tranquility. I do not think the pursuit of knowledge is an exception to this rule. If the study to which you apply yourself has a tendency to weaken your affections, and to destroy your taste for those simple pleasures in which no alloy can possibly mix, then that study is certainly unlawful, that is to say, not befitting the human mind. (34) 7

Description: