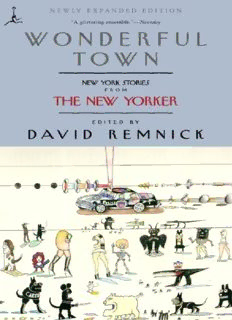

Wonderful Town: New York Stories from The New Yorker PDF

Preview Wonderful Town: New York Stories from The New Yorker

NEW YORK STORIES FROM THE NEW YORKER Edited by David Remnick with Susan Choi RANDOM HOUSE • NEW YORK ©2000 by The New Yorker Magazine. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. All of the stories in this collection were originally published in The New Yorker. The publication date of each story is given at the end of the story. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wonderful town : New York stories from The New Yorker / edited by David Remnick with Susan Choi 1. New York (N.Y.)—Social life and customs—Fiction. 2. City and town life—New York (State)—New York—Fiction. 3. Short stories, American—New York (State)—New York. 4. American fiction—20th century. I. Remnick, David. II. Choi, Susan. PSS49.N5 WS8 2000 813'.010832 74 71—dc21 99-048838 p. cm. ISBN 0-375-50356-0 (alk. paper) RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Random House website address: www.atrandom.com First Edition Book design by Jo Anne Metsch DAVID REMNICK is the editor of The New Yorker. He began his career as a sportswriter for The Washington Post and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for Lenin’s Tomb. He is also the author of Resurrection, The Devil Problem and Other True Stories, a collection of essays, and King of the World. He lives in New York City with his wife and three children. SUSAN CHOI was born in Indiana to a Korean father and the American daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, and grew up in Texas. Her first novel, The Foreign Student (1998), won the Asian-American Literary Award for Fiction and was a finalist for the Discover Great New Writers Award at Barnes & Noble. She is the author of three other novels, American Woman (2003), A Person of Interest (2008), and My Education (2013). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The novelist and former New Yorker staff member Susan Choi worked tirelessly reading hundreds of short stories set in New York, from the sketches of the earliest days of The New Yorker onward. Her insight into the magazine’s evolution over seventy-five years and her sensitivity as a reader were invaluable. I am grateful, as well, to Roger Angell, who gave an order to the selections; to Bill Buford, Deborah Treisman, Cressida Leyshon, Alice Quinn, Meghan O’Rourke, and many others at the magazine (from John Updike, who is represented here, to some of the fact checkers, who will no doubt be in similar anthologies, sooner or later). Thanks are also due Pamela Maffei McCarthy and Eric Rayman at The New Yorker for making arrangements with Daniel Menaker and Ann Godoff of Random House; and thanks to Brenda Phipps, Beth Johnson, and Chris Shay and his library staff, all of whom were essential in making this book possible. CONTENTS David Remnick • Introduction John Cheever • The Five-Forty-Eight Ann Beattie • Distant Music Irwin Shaw • Sailor off the Bremen Tama Janowitz • Physics Woody Allen • The Whore of Mensa Deborah Eisenberg • What It Was Like, Seeing Chris John O’Hara • Drawing Room B Peter Taylor • A Sentimental Journey Donald Barthelme • The Balloon Philip Roth • Smart Money Laurie Colwin • Another Marvellous Thing Jonathan Franzen • The Failure Sally Benson • Apartment Hotel Frank Conroy • Midair James Thurber • The Catbird Seat John Updike • Snowing In Greenwich Village Maeve Brennan • I See You, Blanca Lorrie Moore • You’re Ugly, Too Vladimir Nabokov • Symbols and Signs Jamaica Kincaid • Poor Visitor Hortense Calisher • In Greenwich, There Are Many Gravelled Walks John McNulty • Some Nights When Nothing Happens Are the Best Nights in This Place J. D. Salinger • Slight Rebellion off Madison Renata Adler • Brownstone Isaac Bashevis Singer • The Cafeteria Veronica Geng • Partners Niccolo Tucci • The Evolution of Knowledge Susan Sontag • The Way We Live Now Julie Hecht • Do the Windows Open? Edward Newhouse • The Mentocrats Daniel Menaker • The Treatment Dorothy Parker • Arrangement in Black and White William Melvin Kelley • Carlyle Tries Polygamy Jean Stafford • Children Are Bored on Sunday James Stevenson • Notes from a Bottle Daniel Fuchs • Man in the Middle of the Ocean Ludwig Bemelmans • Mespoulets of the Splendide William Maxwell • Over by the River Jeffrey Eugenides • Baster E. B. White • The Second Tree from the Corner Bernard Malamud • Rembrandt’s Hat Elizabeth Hardwick • Shot: A New York Story Saul Bellow • A Father-to-Be S. J. Perelman • Farewell, My Lovely Appetizer INTRODUCTION FROM THE MOMENT HAROLD ROSS published the first issue of The New Yorker, seventy-five years ago (cover price: fifteen cents), the magazine has been a thing of its place, a magazine of the city. And yet the first issue is a curiosity, a thin slice of the city’s life, considering all that came after. Dated February 21, 1925, it offers only a hint of the boldness and depth to come, just a whisper of the range of response to its place of origin. What was certainly there from the start, however, was a determinedly sophisticated lightness, a silvery urbane tone of the pre-Crash era that was true to its moment (in some neighborhoods) and which also became the magazine’s signature. Of the issue’s thirty-two pages, nearly all are taken up with jokes, light verse, anecdotes, squib-length reviews, abbreviated accounts of this or that incident, and harmless gossip about metropolitan life. With Rea Irvin’s Eustace Tilley peering through his monocle at a butterfly on the cover, with its cartoons and drawings of uptown flappers, Fifth Avenue dowagers, and Wall Street men with their mistresses out on the town, with its very name, the magazine announced its identity—or at least the earliest version of it. There was a column called “In Our Midst” that delivered one-sentence news briefs on the city’s forgotten and barely remembered (“Crosby Gaige, of here and Peekskill, is leaving for Miami next week to join the pleasure seekers in the sunny southland”); there was “Jottings About Town” by Busybody (“A newsstand where periodicals, books and candy may be procured is now to be found at Pennsylvania Station”); there were reports of overheard talk on “Fifth Avenue at 3 P.M.,” musical notes by “Con Brio,” and theater notes by “Last Night.” With an advisory board of editors that included Irvin, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, and Alexander Woolcott, Ross’s first issue had the feel of an amusement put together by an in-crowd of amused, and amusing, New York friends. One of the squibs, called “From the Opinions of a New Yorker,” is typical of the throwaway, unearthshaking tone of that first issue: New York is noisy. New York is overcrowded. New York is ugly. New York is unhealthy. New York is outrageously expensive. New York is bitterly cold in winter. New York is steaming hot in summer. I wouldn’t live outside New York for anything in the world. It was essentially impossible to see what a various and ambitious publication The New Yorker would become. In his original prospectus for the magazine, Ross said he intended to publish “prose and verse, short and long, humorous, satirical and miscellaneous.” No mention of fiction. The literary side of things did not initially strike Ross as right for him or even worth the struggle. For one thing, the competition for fiction seemed forbidding: Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, fat with advertisements, were publishing such authors as Fitzgerald and Hemingway, Lewis and Dos Passos, and paying them handsomely. Often enough they wrote their novels for art, their stories to live. Ross would later admit that he didn’t pursue Hemingway “because we didn’t pay anything.” And as Thomas Kunkel, Ross’s wonderful biographer, points out, Ross’s preferences ran to humorous sketches and commentary—“casuals.” Any trace of seriousness made him jumpy. Fiction eventually became an essential part of the magazine for two reasons. When Ross hired Katharine White, in 1927, he was bringing into the magazine someone of enormous literary sophistication, someone who adored him but was willing to argue with him—and able to win. Her singular victory was the establishment of fiction as a regular component of The New Yorker. The second reason for the rise of fiction in the magazine was the American mood. With the Crash of the stock market, in 1929, the magazine’s chronically bemused tone suddenly seemed out of step and out of tune. More and more, Katharine White succeeded in getting short stories—and short stories of a deeper sort—into the magazine. But what kinds of stories? There have been many essays, some critical, some rather too defensive, describing a species of fiction known as “the New Yorker story”—a quiet, modest thing that tends to track the quiet desperation of a rather mild character and ends in some gentle aperçu of recognition or dismay—or dismayed recognition. Or some such. The minor key, that was the essential matter. Somerset Maugham once described it as “those wonderful New Yorker stories which always end when the hero goes away, but he doesn’t really go away, does he?” Even White herself despaired of the “slight, tiny, mood story.” And while it is true that a certain kind of wan tone infects the lesser stories of the period, White, as well as her successor Gustave Lobrano, were remarkably successful in finding new young writers—often enough New York writers—who gave the magazine an original kind of vitality and its readers something mysterious and lasting to hold on to as the weekly issues came and went. Among the first great New York writers that Katharine White began to

Description: