Thomas, Lucy and Alatau: The Atkinsons’ Adventures in Siberia and the Kazakh Steppe PDF

Preview Thomas, Lucy and Alatau: The Atkinsons’ Adventures in Siberia and the Kazakh Steppe

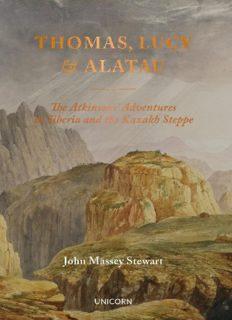

THOMAS, LUCY & ALATAU The Atkinsons’ Adventures in Siberia and the Kazakh Steppe John Massey Stewart Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799–1861) For Penelope (née Lynex), cellist, 1936 – 2015, my remarkable wife of fifty years Contents Title Page Dedication Prologue: England and Germany One St Petersburg and First Travels Two Into the Altai Three Into the Kazakh Steppe Four Life and Death in a Cossack Fort Five The Mountains, the Steppe and the Chinese Border Six Eastern Siberia Seven Barnaul, Belukha and back to St Petersburg Eight Return to England Nine Lucy and Alatau Epilogue Appendix I Appendix II Catalogue Raisonné Notes Bibliography Glossary Acknowledgements Index Illustration credits Copyright Imaginary Greek landscape by T.W. Atkinson, probably painted before his Russian travels. Prologue England and Germany WOLVES AND SNOWSTORMS, camels and unbearable desert heat; bandits, murder attempts and night raids by enemy tribes; precipices, dangerous rapids; convicts, Cossacks, nomads – as well as balls and a fourteen-course dinner party for an archbishop: all this (and far, far more) was experienced in Thomas Witlam Atkinson’s seven years’ travels with wife and infant son by foot, horse, sledge, carriage, boat and raft for nearly 40,000 miles in the remoter parts of the Russian Empire, resulting in 560 watercolour sketches and fame as ‘the Siberian traveller’. It had all begun in the year 1846 when a forty-seven-year-old, humbly- born Yorkshireman, stonemason and architect wrote the following letter: To His Imperial Majesty Nicholas the First, Emperor of All the Russias Sire, The encouragement which your Imperial Majesty has always extended to Art and Science induces me to petition for your gracious permission to visit a province of Your Imperial Majesty’s Mighty Empire, The Pictorial features of which have not yet been much developed. It has been suggested to me by Baron Humboldt [the famous scientist, explorer and geographer] that the Ural and Altai mountains would supply numerous and most interesting subjects for my pencil. I am induced to hope that my great experience in sketching and painting would enable me to bring back a vast mass of Materials that would illustrate these portions of your Imperial Majesty’s Empire. As I should be accompanied by a gentleman who has devoted much time to Geology he would take notes of the Geological features of the Country and thus I wish render our united labours of great value. Permit me Sire in profound deference to solicit permission to lay before Your Imperial Majesty my drawings of India, Egypt, Greece as a proof of my competence for such an undertaking. With sentiments of Profound respect for your Imperial Majesty I subscribe myself Sire, Your Imperial Majesty’s most devoted and most faithful servant T.W. Atkinson St Petersburg 19 August 18461 This is the extraordinary story of a village lad born a little over two hundred years ago who rose from nothing to being a successful architect, gave up all to travel with a passport granted by Tsar Nicholas I for remote parts of the Urals, Siberia and what is now Kazakhstan, returning with hundreds of watercolour sketches now mostly lost, of the books he wrote and the fame he won and his descent into near-oblivion today. It is a story too of his indomitable wife, Lucy, and of what became of her and of their son, Alatau Tamchiboulac Atkinson, born in a remote Cossack fort, and his own significant career in Hawaii. It is a story of a talented and ambitious self-made man, of determination, endurance, narrow escapes from death – and love. It is a story that includes many famous people both in England and Russia, embracing Queen Victoria and two Tsars, Palmerston, Charles Dickens, Livingstone and the famous Decembrist exiles. But it is a story too of the conflicting demands of artistry and reputation on the one side and fidelity on the other. The village of Cawthorne, mentioned in Domesday Book, lies on a hillside in the lee of the Pennines. At the end of the eighteenth century most of the 1,000-odd inhabitants were labourers working on the land or in some trade, and the quiet, middle-class village of today (bypassed now but then on the main turnpike road from Manchester to Barnsley) is bereft of those earlier coal and ironstone mines, tanneries, mills and smithies and their bustle. Built of the local grey stone, the village was basically part of the Cannon Hall estate owned by the Spencer Stanhope family, and the eighteenth-century mansion set in a rolling, landscaped parkland lies half a mile from the village. Head mason on the estate then was a widower, William Atkinson, who fell in love with and married a housemaid in the big house, Martha Witlam. To them was born on 6 March 1799, in their ‘two-up two-down’ next to what was then the Wesleyan chapel, a son, Thomas. Thomas’s birthplace, Cawthorne Thomas was born in one of these two end houses in 1799. Next door was a Wesleyan chapel, but it is not known which was which.

Description: