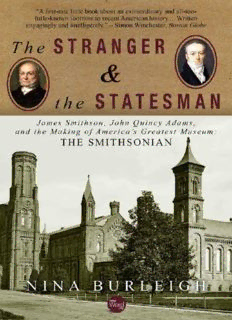

The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum PDF

Preview The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America’s Greatest Museum

Published by New Word City LLC, 2015 www.NewWordCity.com © Nina Burleigh All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-1-61230-849-4 I am deeply grateful to editor Rachel Kahan for first suggesting this story. My agent Deborah Clarke Grosvenor encouraged me to write it and, without her vision, the project would never have gotten off the ground. I have been very fortunate to have a fine editor in Claire Wachtel, whose enthusiasm has never flagged. I would also like to thank Bill Cox at the Smithsonian Archives; Smithsonian paleontologist Ellis Yochelson for his ideas and materials; David Smith at the New York Public Library for always going beyond the call of duty; Rodolf De Salis for research help in London; Nausicaa Pouscoulous in Paris, Marc Rothenberg at the Smithsonian, Dr. Frank James at the Royal Institute, Neil Chambers at the Museum of Natural History in London; American historian Michael Conlin; Brian Dolan; Edwin Grosvenor; Pascale Heurteul at the Musee d’Histoire Naturelle; Fabienne Queyroux at the Institut de France; Peter Schimkat; Jennifer Pooley at William Morrow; Allan Metcalf at MacMurray College for early support and Latin translation. For lodging and laughs in Washington, D.C., thanks to DeeDee Slewka; for the same in New York, Ed Rollins. ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL did not spend the Christmas season of 1903 in the festive tradition. Instead the inventor of the telephone and his wife, Mabel, passed the holiday engaged in a ghoulish Italian adventure involving a graveyard, old bones, and the opening of a moldy casket. They had traveled by steamship from America at their own expense and made their way down to the Italian Mediterranean by train. The entire route was gloomy, as befit their mission. The feeble European winter sun dwindled at four o’clock every afternoon and rain fell incessantly, but the Bells were undeterred. There was little time. They were in Europe to disinter the body of a minor English scientist who had died three-quarters of a century before and bring it back to America. The couple arrived at Genoa a few days before Christmas and checked into the Eden Palace Hotel perched on the edge of the medieval port. The hotel was a pink, luxurious resort in summer, but in winter, drafty and exposed. The city itself spilled down the steep hillsides to the edge of the sea, a shadowy warren of fifteenth-century cathedrals and narrow, twisting alleys that had seen generations of plague, power, and intrigue. Once an international center of commerce and art, with palazzi and their fragrant gardens stretching to the water’s edge, Genoa in winter at the turn of the twentieth century was a grim place with a harbor full of black, coal-heaped barges. A steady rain had been falling on France and Italy for days, in Genoa whipped almost vertical by the tramontane, icy winds that blow down from the Alps into the Mediterranean in the winter. Mabel Bell had been hoping to alleviate the dolefulness of the duty by touring the city, but because of the weather she was unable to walk the alleys and visit the pre-Renaissance palazzi once inhabited by Genoa’s doges. She was forced to sit in the grand lobby of the Eden Palace Hotel, watching the palms beyond the rattling panes get thrashed in the wind, and wait as her husband sorted through the tangled bureaucracy involved in disinterring a body in Italy. The Bells had come to Italy in haste because the remains of James Smithson - minor eighteenth-century mineralogist, bastard son of the first Duke of Northumberland, and mysterious benefactor of the Smithsonian Institution - were in peril. Seventy-seven years before, Smithson had, for unknown reasons, bequeathed his fortune - the equivalent of $50 million in current money - to the United States to fund at Washington, D.C., an institution, in his words, “for the increase & diffusion of Knowledge among men.” Now the bones of this strange and still little-understood man were about to be blasted into the oblivion of the Mediterranean Sea. Smithsonian officials had tried in early years to learn more

Description: