The Rolls-Royce Armoured Car PDF

Preview The Rolls-Royce Armoured Car

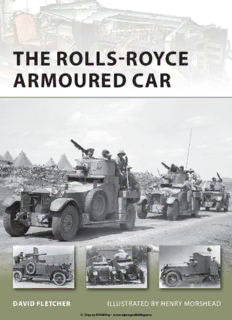

THE ROLLS-ROYCE ARMOURED CAR DAVID FLETCHER ILLUSTRATED BY HENRY MORSHEAD © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD • 189 THE ROLLS-ROYCE ARMOURED CAR DAVID FLETCHER ILLUSTRATED BY HENRY MORSHEAD © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DESIGN 8 WORLD WAR I 12 • Naval operations • The Machine Gun Corps (Motors) • Gallipoli • ‘They searched the whole world for war’ • The Yeomanry • India THE INTERWAR YEARS 23 • An interim design • The 1920 Pattern cars • The Royal Air Force • Ireland • India • The 1924 Pattern cars • Four wheels good – six wheels better WORLD WAR II 43 • The Home Guard BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE ROLLS-ROYCE ARMOURED CAR INTRODUCTION Rolls-Royce: the hyphenated name has become a byword for top quality; you can buy the Rolls-Royce of lawnmowers, of food processors, whatever you like. One never seems to hear Mercedes-Benz used in the same way. It was ever thus; as early as 1906 members of the War Office Mechanical Transport Committee, attending the Motor Car Show at Olympia in London, were seduced by the quality of a 15hp Rolls-Royce, although they had sense enough to realize that at £525 it was far too expensive for the military budget. It takes a war to justify that. The first Rolls-Royce armoured car was privately owned. It belonged to a member of the Eastchurch Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service, which in August 1914 was based in Dunkirk. Its commanding officer, Commander Charles Rumney Samson R. N. was something of a firebrand who supplemented his squadron’s flying activities by ground-based reconnaissance forays using his pilots’ private cars, and these turned into active fighting raids against German patrols operating in the area. As a result of this, and in particular an action at Cassel on 4 September 1914, it was decided to fit armour on to three of these cars, although armour was a relative term. Charles Samson’s brother Felix was the prime mover in this project; however, it was up to Charles Samson himself to obtain authority from the Admiralty Air Department in London. The cars selected were Felix Samson’s Mercedes, a 50hp Rolls-Royce – which may well have been Charles Samson’s own car – and a Wolseley. Work on the cars was undertaken by the Dunkirk shipbuilders Forges et Chantiers de France. Samson admits that the ‘armour’ was 6mm boiler plate, which was only proof against a rifle bullet above 500 yards. Although Charles Samson states that the protective plate was designed by his brother Felix, the pattern is very similar to that seen on some early Belgian armoured cars with a high, V-shaped shield at the back, and a plate covering the radiator and another around the dashboard. It was armed with a borrowed French Lewis gun to begin with and then a water-cooled Maxim, mounted on a tripod and capable of firing over the rear shield. The Belgians had adopted the practice of reversing towards the enemy, ready for a swift getaway should the need arise. This may well have been the idea behind the British design as well. The Royal Naval Air Service, as a branch of the Royal Navy, came under the watchful eye of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, although Samson’s direct superior, as Director of the Admiralty Air Department, was Commodore Murray Sueter. So while Samson experimented with a variety of 4 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com locally built armoured vehicles in Flanders he was urging Sueter, in London, to expand the fleet and inevitably Winston Churchill was interfering. The final number of armoured cars authorised was 60, of which 18 would be Rolls-Royce and 21 each on Wolseley and Clement-Talbot chassis. The design, for some reason, was worked out by the Admiralty Air Department and Lord Wimborne in Britain with no reference to Samson as far as anyone can tell, but the design was submitted to Churchill, who approved it, and a wooden mock-up was created on a real Rolls-Royce chassis to Lord Wimborne’s design. The design did not prove popular with Samson’s men because it offered no protection to anyone whose torso projected above the waist-high armour. The only member of the crew to have a seat appears to have been the driver, who was also sheltered to some extent by a steel hood. For the rest of the crew, however, it was necessary to lie down if they found themselves under fire. The sketch submitted to Churchill showed a car with four potential machine-gun mountings around the body although in practice only two appear to have been provided, with the most popular the one on top of the driver’s hood. In any case, there was only one Maxim to spare for each car. The armour, such as it was, is described as 4mm nickel chrome steel, lined on the inside with oak planks. There are differences in detail between the various cars. Most had some sort of protection for the tyres, while the radiator was covered by an angled plate, although hinged radiator doors are also seen. Eight cars, probably Talbots and Wolseleys, were built by the Royal Naval Dockyard atSheerness but subsequently the armour was fitted by each manufacturer at their works, which might account for the differences. Thecars were organized into four squadrons, each of 15 cars and with crews largely drawn from the The first three of Commander Royal Marines. The first of these, No. 1 Squadron commanded by Lieutenant Samson’s armoured cars must have looked like this, although Felix Samson, was supposed to be equipped entirely with Rolls-Royces. this is the Rolls-Royce showing Samson remarks that ‘the Rolls-Royces proved by far the most reliable and the additional panels of steel suitable’. However, it would be wrong to take the orderly arrangement this covering the radiator, the implies at face value. Flight Commander T.G. Hetherington, who was ordered driver’s position and the machine-gun post at the back. to join Felix Samson’s squadron with four Wolseleys, was horrified by what It is also the only one of these he found in France. Under Charles Samson anarchy reigned, nobody seemed three cars that appears to have to know what was going on and organization was non-existent. Evidence been photographed. © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Samson had one of the original Admiralty Pattern Rolls-Royce cars rebuilt, adding higher sides to protect the crew. It wassometimes seen towing a 47mm gun. Nothing is known about the ultimate fate of the car although Samson later found the gun in Gallipoli and reclaimed it. suggests that none of the squadrons was ever completed, let alone with the makes of car laid down on paper. Yet it was the British penchant for improvisation at its best, where courage and daring made up for a lack of order and it adds a bright page to an otherwise drab account of a long and depressing war. Most of the cars underwent modifications in service. Some had planks, carried in brackets on the sides, which could be used to bridge ditches and narrow trenches, while one Rolls-Royce –probably on Samson’s orders –had a raised body fitted and was sometimes seen towing a 47mm gun on an improvised two-wheeled carriage. In addition to the 15 Rolls-Royces of No. 1 Squadron, two more are listed as being attached to No. 2 Squadron, which, on paper at least, had 12 Wolseleys. It was the only 14-car squadron of the four, always assuming that any of the squadrons ever reached full strength. But events were moving rapidly, both in terms of technology and onthe battlefield. Writing in Volume 1 of The World Crisis Winston Churchill said: ‘Thus at the moment when the new armoured-car force was coming into effective existence at much expense and on a considerable scale, it was confronted with an obstacle and a military situation which rendered its employment practically impossible.’ All four squadrons were operational by October 1914 but whether that implies complete to establishment is unclear, and in any case opportunities for action were diminishing rapidly with the creeping expansion of trench warfare. The Admiralty in London was looking at a new design: a turreted car that offered much more protection for the crew. Flight Lieutenant Arthur Nickerson is the man credited with the design of the turret, although the turret itself was by no means a new idea. Turreted armoured cars had existed since about 1904 though they were mostly prototypes, but the idea of the turret goes back further still, to warships and armoured trains. Nickerson, however, created a turret that offered all-round protection with a minimum of weight; unfortunately its curved sides and thin armour with curved plates were not proving easy to produce. Lieutenant Kenneth Symes was working on it but the best results were achieved by Beardmores in Glasgow. The turret armour was 8mm thick, which made it immune to armour-piercing rounds then employed by the Germans. 6 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Even so there was no obvious uniformity. Examination of surviving In addition to the regular photographs shows dozens of minor variations in the pattern of the armour turreted cars the RNAS staff at and if that were not enough the chassis available differed depending upon Barlby Road, which lies behind the wooden fence, adapted this the year they were built. This may well have been true of all manufacturers Rolls-Royce to carry the heavier but in the case of Rolls-Royce it has been tabulated in great detail and reveals 40mm Vickers Pom-Pom year-on-year changes with continual minor improvements, so each chassis although this presented the number needs to be evaluated in this light. For example, chassis produced gunner with a problem. before 1911 had an exposed drive shaft whereas cars in the 1700 series, produced from 1911 onwards, had the shaft enclosed in a torque tube; chassis produced before 1913 had a three-speed gearbox and from the 1100 series onwards a four-speed box was standard. Unless one knows the chassis number of a particular car this is very difficult to ascertain. As a result it is entirely possible, although by no means certain, that some of the 18 cars earmarked as the first model were completed as the second type, with turrets. During this time the headquarters of what became the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division (RNACD) had moved from its formative site at the Sheerness naval dockyard on the Isle of Sheppey to the Daily Mail airship shed at Wormwood Scrubs in October 1914 although about a month later they left this cold, muddy site for a section of the Clement-Talbot Motor Works facing Barlby Road, North Kensington, less than a mile away to the east. Much of the site was fenced off to enhance security, though this was rather compromised by the open land to the north where it abutted the Great Western Railway. Oddly enough, visitors continued to refer to the site as Wormwood Scrubs and writers still do. The first turreted Rolls-Royce arrived at the RNACD headquarters at Barlby Road on 15 November 1914, having driven all the way down from Glasgow. More would follow over subsequent months. The armoured car is so familiar and seems to follow the distinctive lines of the classic chassis so 7 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com precisely that it is difficult to imagine that it could be anything other than a Rolls-Royce. In practice of course there is so little of the original car to see under the armour that some sort of description is essential. DESIGN It seems to make sense, under the circumstances, to describe the chassis of these cars and the armoured bodies separately. For one thing, with just a few exceptions, the chassis remained the same on all armoured cars from 1914 until 1925 and minor variations can be dealt with where they occur. The design of armoured hulls, on the other hand, changes dramatically over the years and provides the visual identification features necessary to distinguish one type from another, so they probably need to be treated in greater detail. Because in those days Rolls-Royce sold only the chassis to their customers, leaving the choice of bodywork to them from a selection of coachbuilders, it was important that the chassis was robust enough to run without a body and, indeed, strong enough to support some of the more ornate bodies, although the company did issue guidelines when it came to weight. The Silver Ghost chassis had deep, strong side girders braced by five cross- members and at the front by the iconic radiator. Behind the radiator the engine was a straight six, the cylinders grouped in two sets of three with a capacity of 7,428cc with side valves, aluminium alloy pistons and a cast aluminium crankcase. The engine drive passed through a cone clutch to a four-speed and reverse gearbox. In common with many cars of that time both gear lever and handbrake were mounted on the chassis side, to the driver’s right, and of course in those days synchromesh was almost unknown and all the gears were A 1. ORIGINAL RNAS ROLLS-ROYCE IN FLANDERS 1914 This image is taken from a photograph of a group of Scots Guards with an Admiralty armoured caron the Menin Road on 14 November 1914 during the First Battle of Ypres. In all 18 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost chassis were earmarked for conversion to what became known as the First Admiralty Pattern armoured cars although whether all of them were ultimately completed in this form is unclear. Protection was minimal because the armour was too low and too thin to protect the men adequately and the firepower was limited to a naval Maxim machine gun mounted on top of thedriver’s head cover and rifles carried by the crew. For a few weeks these cars enjoyed considerable success in the open country between Ypres and the coast but as the main armies fought their way north, digging trenches, spreading wire and ripping up the ground with artillery fire their operational opportunities were severely restricted. This location later became known as Hell Fire Corner. Also shown is the original Rolls-Royce radiator badge in red, which according to popular rumour changed to black upon the death of Sir Henry Royce in 1933. 2. TURRETED ROLLS-ROYCE OF RNAS, UK, 1915 The classic 1914 turreted Rolls-Royce belonging to a squadron based in the West Country for training. The car is finished overall in khaki green but a splash of colour is added by the large white ensign, flying from a staff attached to the turret. Other features to note are the trumpet of the klaxon horn on the side of the bonnet, the King of the Road acetylene lamp on the rear tray and the two rifles protruding from loopholes in the body. Firing rifles from inside a vehicle such asthis would be difficult at the best of times but with a driver and a machine-gunner in place wasvirtually impossible. The snarling fox’s mask attached to the front of the turret seems to be unique to this car but presumably it summed up the aspirations of the car’s commander, once let loose upon the battlefield. The badge is that of the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division. 8 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 2 1 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com This unusual car, photographed in the desert, not only illustrates the difficulties of desert travel but also shows an otherwise undocumented conversion. Either it was a local modification or, just possibly, the previously illustrated Pom- Pom car in a new guise. square cut, so a skilled driver was taught to double-declutch up and down the box to ensure a smooth gear change. Many less skilled drivers relied on the fact that it was possible to drive the car in top gear in virtually all conditions. However, this could not be done with the weight of an armoured hull on top, so the drivers of these armoured cars were specially trained. Another novelty, the electric starter motor, was not introduced on the Silver Ghost until 1919. Before that time a car was started on a crank handle through a dual ignition system incorporating two high-tension magnetos andtwo separate sets of spark plugs on each cylinder. Cars built before 1917 had a trembler coil in the ignition system which could, with luck, be started ‘on the switch’, although this required some luck and a lot of experience. Suspension was leaf springs all round, semi-elliptical at the front and cantilever at the back. A footbrake operated on the prop shaft, while the handbrake lever acted on the rear wheels only. By 1913 triple-spoked wire wheels were the most common type, by Dunlop or Rudge-Whitworth. Tyres were Palmer Cord pneumatic, although some armoured cars are seen with the special metal-studded tyres that were supposed to prevent skidding. Fuelwas carried in an 18-gallon oval drum at the rear of the chassis delivered under air pressure from a mechanical pump situated at the front or for starting by a hand pump on the dashboard. For the armoured cars certain modifications were introduced but not necessarily all at the same time. An oil tank, normally located on the left side of the chassis was moved into the engine compartment under armour and a 4-gallon auxiliary fuel tank was also introduced, located in front of the driver. Extra leaves were added to the springs in order to beef up the suspension and twin rims were fitted on the rear axle to spread the weight. Rolls-Royce produced two types of radiator, a standard model and a taller one deemed more suitable for colonial use. This second type was also referred to as the Military version although it was not used on the armoured cars because it would have raised the height of the bonnet armour by about two inches andas a result probably the overall height of the vehicle itself. The armour plate, as already noted, was 8mm (0.3in.) thick and it enclosed the engine and fighting compartment. At the front two hinged plates acted as protection for the radiator, operated by a long lever from the driver’s position; since they interfered with the airflow they would only be closed when the car was under fire and the radiator in danger although they were never entirely airtight. Incidentally, it is worth noting that the wheels and 10 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

Description: