The Rise of Ancient Israel PDF

Preview The Rise of Ancient Israel

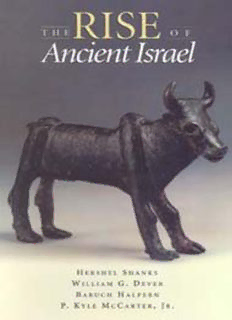

The Rise of Ancient Israel Lectures presented at a symposium sponsored by the Resident Associate Program, Smithsonian Institution October 26, 1991 By Hershel Shanks, William G. Dever, Baruch Halpern and P. Kyle McCarter, Jr. The Rise of Ancient Israel Copyright © 2012 Biblical Archaeology Society 4710 41st St. NW Washington, DC 20016 All rights reserved. First published by the Biblical Archaeology Society, 1992. ISBN: 978-1-935335-81-8 First edition: 1992 ON THE COVER: Bronze bull figurine. Looming large despite its diminutive (4-inch- high by 7-inch-long) size, this bronze bull may come from the only Israelite cultic site yet discovered dating to the 12th century B.C.E. Found at the summit of a high ridge near biblical Dothan, in the Samaria hills north of Mt. Ebal, the bull may have been an offering or it may have been worshiped as a deity. El, the chief Canaanite god, was often depicted as a bull. If the ridge near Dothan is indeed Israelite, it is noteworthy that the only Israelite shrine from the 12th century B.C.E. contains a figurine almost identical to earlier depictions of the Canaanite deity El. Zev Radovan Contents Defining the Problems: Where We Are in the Debate How to Tell a Canaanite from an Israelite The Exodus from Egypt: Myth or Reality? The Origins of Israelite Religion Panel Discussion Acknowledgments Defining the Problems: Where We Are in the Debate By Hershel Shanks We’re going to hear today from three world-class scholars on what may be the hottest topic in biblical studies—the rise of ancient Israel—or, as the scholars like to call it, the emergence of ancient Israel—a little fancier term. Where did the people who became the nation of Israel come from? And when? By what process did they become a nation? What were their religious roots? How did they find their God Yahweh? Scores of scholars are struggling with these issues. Some of the disagreements are intense. Our speakers today are among the leaders in the debate. We may hear from them whether any kind of consensus is emerging. My job is simply to provide the mise-en-scène, to set the stage, so that the scholars who follow me will be able to leap into their subject with an assuredly knowledgeable audience. For many of you, what I say will be elementary; for some of you, it won’t, and I want to bring everybody up to speed. By the time I finish, you will be able to distinguish very easily between the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age (laughter), you will know what the Merneptah Stele is, you will be able to talk about a four-room house and a collared-rim jar and the three models of the Israelite emergence in Canaan. I’m also going to try to provide a little context for you, so that you’ll have in mind the larger picture, the basic framework within which the more focused discussion of the next three speakers will take place. In doing that, I will weave back and forth between the biblical text and the archaeological materials. Because, as some of you know, I shun controversy (laughter), I will present to you only what is unequivocally true and acceptable to everyone. So, what I say, therefore, you can accept. When the next speakers get up, you will hear the more controversial and iffy research. (Laughter.) Let’s begin with the Bible. The Bible begins with the creation of the world and proceeds in the first ten chapters of Genesis to give us a world history—until everyone but Noah and his family are destroyed in a flood. God’s first experiment in creating a world of worthy people fails. So he destroys it and starts all over again. These early chapters of Genesis culminating in the Flood have nothing to do with Israel. In fact, this story provides a contrast with the second attempt to create worthy people. This time God chooses a single family.1 He concentrates on this family—the family of Abraham, the first Hebrew. The rest of the Book of Genesis is the story of this family—first Abraham and his wife Sarah, their son Isaac and his wife Rebecca, their son Jacob and his wives Rachel and Leah and, finally, Jacob’s 12 sons, who become the 12 tribes of Israel. They go down to Egypt and settle in the Delta when a famine grips Canaan. Fortunately for the family, one of the sons, who had preceded the others under difficult circumstances, has risen to a position of authority second only to the pharaoh himself. It is in Egypt that Israel becomes a people—or at least numerous enough to be a people. There they multiply and in the end are enslaved by a pharaoh who “knew not Joseph.” Finally, they escape under the leadership of a man named Moses. They then begin their 40-year trek to the Promised Land. On the way, they experience a theophany at a place called Sinai—or sometimes Horeb. There God gives them a set of laws by which to live. The people enter into a covenant with God in which they agree to obey his laws and in return they become his people, the recipient of his benefices. After their 40-year sojourn in the desert, they arrive, finally, at the Promised Land. Now at this point the Bible gives us two somewhat different accounts of how they took possession of the Promised Land. The first is in the last part of the Book of Numbers and the Book of Joshua. The second and somewhat different account is in the Book of Judges.2 The account in Joshua portrays a lightning military campaign—lasting less than five years. In this campaign, the various peoples of Canaan are defeated; “Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negev and the lowland and the slopes and all their kings” (Joshua 10:40). After these victories, the land west of the Jordan is allotted among the Israelite tribes. The account in Judges is quite different. First of all, the order is reversed. In Judges, the allotment comes first, and after the allotment they attempt to take possession of the land by conquest. In Judges there is no unified effort by “all Israel” to conquer the land, as seems to be the case in Joshua. In Judges the effort to possess the land seems to be the work of individual tribes or groups of related tribes. And most important, Judges makes it clear that by no means was the entire land subdued. In Judges 1 as a matter of fact is a list of 20 cities whose people were not driven out by the newcomers. These cities included Jerusalem, Gezer, Megiddo, Taanach, Beth-Shean and Beth Shemesh (Judges 1:21, 27–33). These are some of the most important cities in the country. So we have quite a difference here between the Book of Joshua and the Book of Judges. Now the events in Judges do purport to occur after the death of Joshua, so the two accounts can be harmonized somewhat by assuming that the picture in Joshua is exaggerated and that the military victories recorded there were not quite so extensive or complete as they are described. In any event, it’s clear that the account in Judges does preserve a tradition that the land of Canaan was possessed over a long period of time. And, if we look carefully, there are hints of this even in the Book of Joshua. During this period, the Israelites are threatened by various Canaanite peoples, but charismatic military leaders called Judges always arise and save them. Eventually, however, this loose Israelite tribal confederacy proves inadequate to defend itself against the Philistine threat. Some more organized structure is needed, so the people ask for a king. And they get a king. Saul is appointed, but his reign is ultimately a failure. He is replaced by Israel’s most glorious king, David, and with his reign, Israel truly becomes a nation. This, in brief, is the biblical account. Until the 20th century, the emergence of Israel in Canaan was almost always referred to as the “conquest of Canaan,” for the Bible clearly portrays it this way. And indeed until after the Second World War, it was generally thought that archaeology supported this view. For a time, archaeology was the darling of the nursery among those who regarded the Bible as literally true. To explain this, I’ve got to give a little of the history of biblical scholarship. In the 19th century, we have a burgeoning of historical, critical biblical scholarship. The impetus is often associated with a strange genius by the name of Julius Wellhausen. He shattered the calm of biblical literalists by breaking down the Pentateuch into four different authorial strands. These different strands of authorship are often designated by the familiar letters J, E, P and D. J stands for the Yahwist (Jahwist in German), E for the Elohist, P for the priestly code and D for the Deuteronomist. These were all put together by a fellow designated R, for the redactor—a fancy name for editor. Julius Wellhausen. A strange genius, this 19th-century (1844–1918) German scholar inaugurated modern biblical scholarship by asserting that the Pentateuch, or five books of Moses, is comprised principally of four strands. These four he designated J (for Yahwist; Jahwist in German), E (for Elohist), P (for the priestly code) and D (for the Deuteronomist). These components, in Wellhausen’s view, were joined together and edited by R, the redactor. In a reaction to Wellhausen’s theories, archaeology became—for a time—the darling of biblical literalists. In the first half of the 20th century, just as the view that the Bible was written by humans during discernible historical periods was gaining ground among scholars, the newly emerging field of archaeology appeared to be validating a key tenet of the Bible: At site after site archaeologists were uncovering destruction levels that seemed to prove that the Israelites conquered Canaan in a swift military campaign as described in the Book of Joshua. Courtesy the Union Theological Seminary Archives, The Burke Library, NYC All this was very disturbing to biblical literalists. And at this point—in the first half of the 20th century—archaeology seemed to come to the rescue. The short of it is that in tell after tell, archaeologists found a destruction level that they thought they could identify with the Israelite conquest of Canaan. Well, archaeology is no longer a crutch in this classic sense of the conquest model. We simply can no longer posit a series of destructions in Canaan that can rationally be identified as the result of the Israelite conquest. Recently, our archaeological methodology has improved, we can date levels much more securely and more sites have now been excavated. As a result, we can no longer say that archaeology supports what we may call the conquest model of Israel’s emergence in Canaan. Some sites like Jericho and Ai appear to have been uninhabited at the time

Description: