The Republic of Art and Other Essays PDF

Preview The Republic of Art and Other Essays

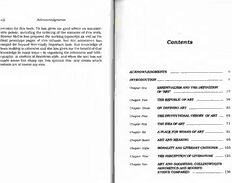

viii Acknowledgments revision for this book. He has given me good advice on innumer able points, including the ordering of the contents of this work. Myrene McFee has prepared the working typescript as well as the final prototype pages of this volume, but her assistance has Contents ranged far beyond this vitally important task. Her knowledge of book making is extensive and she has given me the benefit of that knowledge in many ways- in organizing the references and bibli ography, in matters of American style, and when the text has not made sense her sharp eye has spotted this. Any errors which remain are of course my own. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One ESSENTIAUSM AND THE DEFINITION OF'~' ........................................................................... 17 Chapter Two TllE REPUBUC OF ART ........................................ 39 Chapter Three ON DEFINING ART ................................................... 53 Chapter Four TllE INSTmmONAL THEORY OF ART ...... 63 Chapter Five 'l1lE IDEA OF ART ....................................................... 71 Chapter Six A PIACE FOR WORKS OF ART ........................... 81 Chapter Seven ART AND MEANING ................................................. 95 Chapter Eight MORAUTY AND UTE.RARY CRITICISM. ....... 105 Chapter Nine THE PERCEPTION OF UTERATURE ............ 125 Chapter Ten ART AND GOODNESS: COLLINGWOOD'S AESTHETICS AND MOORE'S ETHICS C01'fi>ARED ............................................... 139 INTRODUCTION Chapter Eleven AESTHETIC INSTRUMENTALISM .................. 159 Chapter Twelve EVALUATION AND AESTHETIC APPRAISALS ................................................................ 1 75 Chapter Thirteen THE EVAUJATION OF A WORK OF ART: It has come to be a commonplace in contemporary aesthetics as THE PROBLEM OF MINIMAUSM .................. 195 studied by professional philosophers in the English-speaking world that, for reasons explored in the first chapter of this book, Chapter Fourteen AESTHETICS AND AESTHETIC "Essentialism and the Definition of 'Art'," it is a philosophical EDUCATION (AND MAYBE mistake to seek out the necessary and sufficient conditions MORALS TOO} .............................................................. 21 7 which govern the applicability of the term "art." There are no such conditions, so it is widely held. Now I myself evidently must ac Chapter Fifteen THE IDEA OF AESTHETIC cept that this is so, in that I nowhere attempt to state what these EXPERIENCE ................................................................ 225 conditions are. Nevertheless, I must confess to being drawn to those theories of art, such as Tolstoy's, and Clive Bell's, where Chapter Sixteen SCHOPENHAUER'S ACCOUNT OF the author has felt no such inhibitions in laying down conditions AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE .................................. 239 for the applicability of the term "art." And that is the point. What is of deeper interest is not the so-called "mistake" in this under Chapter Seventeen COLLINGW OOD'S PRINCIPLES OF ART: taking, but what it is that we can learn about the concept of art. AESTHETICS AND PHIWSOPHICAL from the fact that it seems to lend itself precisely to this sort of METHOD .......................................................................... 255 stipulation. For in this respect art is different from many, but not from all, other concepts. Chapter Eighteen NATURAL BEAUTY WITHOUT The prohibition against essentialism is so deeply en METAPHYSICS ............................................................. 273 trenched in contemporary aesthetics that we run the risk of its cutting us off from important insights in the field which would Notes ................................................................................................... 295 otherwise be available to us. As I shall suggest below, the cry against essentialism prevents us from seeing, for example, that a Bibliography ................................................................................................... 327 good deal of aesthetics is in fact to do with arguments over, and commitment to, certain ideals. Another example is this: the fact I~ ................................................................................................... 339 that Collingwood is widely believed to have committed the so called essentialist fallacy I believe has prevented a proper 2 Introduction Introduction 3 consideration of his Principles of Art. So in Chapter Seventeen, but to explain, say, what it was to read a poem, any poem, as op "Collingwood's Principles of Art: Aesthetics and Philosophical posed, for example, to what it was to read an instruction manual. Method," I consider whether Collingwood is in fact in any damag My work has been much influenced by this dogma, without either ing sense an essentialist. my having declared allegiance to it or rebelled against it. Essentialism is not of course the only issue, nor indeed the Regarding the second orthodoxy, in applying Waismann's most important to arise in a consideration of Collingwood's aes doctrine of open-textured concepts to art, I observe that Wais thetics. There is too the systematic character of this aesthetics to mann's views strictly speaking applied to empirical concepts-as be studied. The systematic characteristic of Collingwood's work if art were not an empirical concept. The not-so-hidden premise renders it the shining exception to the piecemeal style in which here is that if something is an evaluative concept. which I hold art the subject is nowadays commonly treated. to be, then it cannot be an empirical concept. And what does this Philosophically, I am more interested in such questions as, assumption rest upon but the dogma that there is a logical differ say, the nature of definition, than I am in seeking to recapture in, ence between "is" and "ought," where the "is" is empirical and the and for, philosophy a kind of phenomenological repetition of the "ought" is evaluative? In aesthetics this means. for example, that first-hand experiences to be had from looking at a particular to say Clive Bell's theory of art propounds an evaluative concept painting, reading a certain poem, or, for that matter, writing one. of art is to say that Bell's theory enjoins that one ought to prefer In this matter I have inherited the sins of my philosophical the paintings of, say, Cezanne to those of Landseer. fathers. (And it was fathers; for there were few if any mothers in Some aestheticians have implied that aesthetics is impover my philosophical education.) ished by undue attention to the question of what art is.1 I do not In Chapter Seventeen, then, as also in Chapter Ten, "Art think for one moment that the question is the only one, or even and Goodness: Collingwood's Aesthetics and Moore's Ethics the most important one, in aesthetics. As I say in the introduc Compared," my longstanding interest in philosophical method, tion to Chapter Two, "The Republic of Art" (and repeat at the end an interest not surprising in a student of Stephan Korner's, of Chapter Five, "The Idea of Art"). it is easy to exaggerate the im comes to the fore. This interest naturally includes an interest in portance of the question "What is art?". Dozens of questions have what was once called the logic of concepts. An example of this is been tackled piecemeal in recent aesthetics without the question the point I make in Chapter One, "Essentialism and the Defini about what art is ever having to come in: questions about repre tion of 'Art'," that "work of art" is not a predicate, but a subject of sentation, meaning, metaphor, the expression of emotion, fic predication. I would like philosophy to make available a logical tionality, and many more. Although these questions are often grammar of the concept of art in which facts such as these, if handled in aesthetics without any interest being evinced in the they are facts-and I have been a bit disappointed that one question of art, I have been drawn. nevertheless, to the question doesn't get this kind of question discussed more often in aes "What is art?", partly because in classical writings in aesthetics, thetics-are systematically set out. displayed, and explained. although not in contemporary ones, those propounding philoso When I was an undergraduate, two of the then entrenched phies or theories of art were also dealing with these other ques orthodoxies were that philosophy was a meta- or second-order tions. I think that these so-called traditional writers would have enterprise, and that between fact and value, between "is" and been surprised by the idea that one could keep the various "ought," there was a gap or chasm that could not be bridged. In inquiries separate. It is only recently that we have adopted the obedience to the first ort~od . you might, as a private citizen, piecemeal approach to aesthetics: the expression of emotion this read a poem; but your tas as a philosopher was not to re-enact week, metaphor next, and the meaning of art (if we get there) the that reading as a good c tic or civilized conversationalist might, week after that. 4 Introduction Introduction 5 It was only some considerable time after I had first pub term "art" as the idea of art has developed historically. However, it lished "The Republic of Art" that I discovered (as I say in the was in the first instance from Nietzsche and not from Hegel that I introduction to Chapter Four, "The Institutional Theory of Art") took the idea that if something were a social practice with a that I had propounded an institutional theory of art. without history, or indeed many practices, it seemed foolish to search for knowing it-notwithstanding the fact that I actually use the term the necessary and sufficient conditions governing the appli "institutional" in the text, and I talk too about the status of art cability of the concept in question. However, I do not think that being conferred upon a work of art by the judgment of the public. reference to the historicity of the concept of art gets us off scot When I wrote "The Republic of Art" it did not occur to me that I free. For if. to put it most portentously, philosophy is the study of was proposing a theory of art which was coming, notably in the things as such, we then have to answer the more difficult work of George Dickie, to have its own name. I did not come question, how are philosophy and history together possible? across Dickie's work until later: first. I think. when he sent me The problem, with which I have been much occupied in my some portion of the manuscript of what was to be his Art and the recent work on Collingwood, and which is a problem in general Aesthetic for comment.2 philosophy and by no means confined to aesthetics, is to ex Originally I got the idea for thinking of art in institutional plain-if one is interested in what art as such is, which one must terms not from any work in aesthetics, but from wondering be if there is to be a philosophy of art and not merely a history whether G.E.M. Anscombe's distinction between brute facts and how that which is properly thought of as art gets grounded in institutional facts might apply to the statement "X is a work of what is otherwise a chronicle of adventitious and contingent art." Could one say the statement "X is a work of art" is a state change, where nothing can be privileged as properly this or ment not of a brute fact but of an institutional fact?3 Without, I properly that (because if it were, how could it lose the title, or at hope, sounding unduly chauvinistic, one can find further British least be forced to share it with new and unlike usurpers, which it provenance for institutional theories in the use of the term "insti must if subject to historical change?). In other words, how can tutional" in Anthony Quinton's "Tragedy," an essay which I came definition get a purchase where there is only process. fluctuation, across very early in my studies in aesthetics.4 I was alert to the and change? metaphor of the republic of letters from my studies in, and love The Institutional theory of art has been subjected to a lot of of, eighteenth-century literature. criticism, much of it severe, in recent years. However, as I imply in In any account we give of the concept of art we must remem Chapter Four, "The Institutional Theory of Art," but do not per ber that the concept has a history. Exactly what to make of this haps state strongly enough there, I have not changed my mind claim is not easy to say. and in a full treatment of the topic of the on the basic intuition that if we want an answer to the question, historicity of concepts much would have to be said about the his "What is art?", we should continue to look in the direction of the toricity of other concepts.5 Collingwood is the modern British institutional theory. But to arrive at a satisfactory result, those philosopher most mindful of historicity, and behind him, of criticisms would have to be met, including some that I have ad course, lies the influence of Hegel. And it is Hegel's approach to vanced myself in Chapter Three, "On Defining Art," against my history which I find more fruitful in thinking about the concept of original "republic" model. My view, however, is that the criticisms art than, as it were, Hegel's official aesthetics. should make us sharpen the position and not abandon it. In "On Defining Art" (Chapter Three). I see Hegel's histori In "On Defining Art," first published in 1979, I observed that cism as offering a midway course between the extremes of an approach such as Plato's to the concept of art leaves us with a Platonism and Wittgensteinianism, as there defined. In other wholly mysterious question of how a metaphysical idea of art words, it is a philosophical task to articulate meanings of the could be independent of, and survive the disappearance of, works 6 Introduction Introduction 7 of art. I now see two possible answers to this objection. The first is fact that the work of art is created in a medium. So to understand to be found in the distinction Francis Sparshott draws in his a work has to do with following in a medium. monumental book, The Theory of the Arts, 6 between art and a As an undergraduate I took a joint honours course in phi work of art. If we follow his argument, we can see how art will be a losophy and English literature. The experience was in one or two motivating idea without having to be tied to particular works of respects, notably as pertaining to the question of what morality art. And I certainly need, for the "Republic of Art" to work, the is, quite schizophrenic. The term "moral" as used in literary criti converse possibility: namely, that there may (ontologically) be cism seemed quite different in meaning-for one thing, it seemed some works of art which are not art. I assume, but perhaps do invested with a heavier transcendent and cloudier significance not make explicit enough in !he Republic of Art," that there can from its meanings to be found in orthodox moral philosophy, be works of art (in the ontological sense, paintings, poems, sculp with there a heavy emphasis on duty and on action, or else on tures, etc.) which are not worthy of nor aspire to the status or character and virtue. But neither strand within philosophical condition of "art." ethics came anywhere near the meanings of "moral" apparently The second answer to the objection that it is mysterious envisaged by many literary critics. This is the starting point of how an idea of art could be independent of works of art is implied Chapter Eight, "Morality and Literary Criticism." in the text that appeared slightly earlier than "On Defining Art," One difference between the philosopher's approach to namely "The Idea of Art", here Chapter Five. In this chapter, I ethics and the literary critic's, which I don't say bluntly enough claim, applying some ideas of Coleridge's, that art is an idea and in the original paper, is that Enlightenment secularism has gone not a concept. This leans heavily on the supposition of some quite much further in philosophical ethics than it had, at least down to sharp logical differences between ideas and concepts, ~d allows the time of the so-called New Critics, in literary criticism. Or put for the Platonist possibility I objected to above that there could be ting this the other way around, many uses of the term "moral" in an idea of art that was not realized in any particular works. One criticism were invested With religious significance. I say "were" should not, of course, be surprised at the possibility of Platonism since I assume that such uses Will have become a casualty of the being allowed for in anything that bears upon it the influence of post-Structuralist critique of humanism. Coleridge. And, although I continue to see the importance of He Wittgenstein's dictum that ethics and aesthetics are one is gelian historicism for aesthetics, 7 anything which places itself in famous. I prefer, however, to look not for identities but for affini the school of Coleridge will, given Coleridge's date of birth and the ties, but in the matter of morality there is just a blank disconti influences on him, represent a retreat into the pre-Hegelian nu~ty between the practical accounts of the moral offered by metaphysics of Kant and of Plato. p~Ilosophers and the religious assumptions of some literary In Chapter Six, "A Place for Works of Art," I contend that cntics.8 However, there is the possibility of some mediation here one of the central features of the concept of copying is that copies via the concept of ideals. I believe that American philosophers, are done or expressed in a medium. This is the first mention in such as John Dewey, had a better grasp of the converging in ide my work of the concept of a medium, an idea which needs much als of the aesthetic and the ethical than many British philoso more attention in the philosophy of art than it commonly gets. I phers, though we are in debt to a British philosopher, Richard take matters concerning the media of art a little further, but not Hare, for his pioneering work on ideals. I find Hare's account of far enough, in Chapter Seven, "Art and Meaning." In that chapter ideals one of the most interesting aspects of his Freedom and I propose that to get at the idea of meaning in art we need to Reason, and more important, certainly for aesthetics, than his connect the idea of meaning with understanding, and further, much more frequently discussed account of moral judgments as that to understand a work of art is crucially connected with the universalizable prescriptions. 9 I ntrod uctio n 9 Introduction 8 In "Aesthetic Instrumentalism," incidentally, I employ the To do further work on the logic of ideals would be to work at device, common in my work, of taking of some observation of a a crucial intersection of ethics and aesthetics. So just as I would philosopher on some matter outside aesthetics-for example, like to see more work done in aesthetics on the concept of the some remark of Kant's on the autonomy of a rational being or of medium in art. I think an understanding of the aesthetic would Nietzsche's criticisms of Socrates-and seek to apply it to' some be extended through an analysis of ideals. I suppose it is a com problems within aesthetics. My use in this manner of some ideas mon assumption in philosophical scholarship, perhaps in all of Josiah Royce's (in Chapter Six, "A Place for Works of Art") grew scholarship, to believe that the work not yet done is more in out of my longstanding interest in classical American philo teresting and important than what has been done. The most sophy. interesting questions are generally those which a paper stops The dispute between autonomists and instrumentalists short of or which stop, that is, halt it. al~o ~nvolves some much bigger questions, not commonly dealt Indeed, the contest between what in Chapter Eleven, "Aes- with m aesthetics, at least not since the work of Schiller, on how thetic Instrumentalism," I call aesthetic instrumentalism (the we can .cons~stently defend human freedom and the possibility in view that the value of a work of art consists in the function it ful the social sciences of explaining human action. Thus, on some in fils) and aesthetic autonomy (which is aesthetic instrumental strumentalist views of art, the functions that art in society ism denied, rejected, or negated) and the counter-claim that the serves are stressed, but this, I argue in the chapter on Aesthetic work of art is intrinsically valuable, valuable for its own sake, Instrumentalism, will not explain the nature of the value that we could be seen as a contest over ideals. This is particularly appar as individuals or subjects phenomenologically find in or attribute ent if I am right in my claim that whereas instrumentalists th~nk to the work. autonomists trivialize art the autonomists in their tum thmk Of course, sociologists of art, such as Pierre Bourdieu have that instrumentalists are philistine or puritan. The autonomist in effect proceeded on the assumption that there cannot be~ phi seeks pleasure, delight, and enjoyment from art while ignoring losoph~ of taste, merely a sociology of it. But this, as I argue in the truth which art teaches and its contribution to human my review of Bourdieu's Distinction, 10 evades the question of how welfare, which the instrumentalist regards as frivolous. The my tastes, when I discover that these are nothing but the inevi autonomist thinks in return that anybody who talks about the table or typical preferences of people like me, should or ought to contribution of art to human welfare has never looked at a work be established. If it turns out that my kind of person-that is, of art. people of my class, occupation, gender, or whatever it is that What is this but an argument over ideals? In "Aesthetic In- makes me typical, and not the unique individual I thought I was strumentalism" I imply that these arguments can be made more predictably listens to a certain sort of music, or indeed cares for or less plausible, depending on what function we claim the work music at all, so what? of art is to perform. Various theories are on offer here: for exam The real question, when I discover from sociology that the ple, those of Schopenhauer and Tolstoy. I have found such in values and tastes, on which in the Kantian manner I plumed my strumentalist theories among the most interesting topics to be self as differentiating me from everyone else, are the predictable offered in the historical or classical literature on aesthetics. This values and tastes of somebody of my type, however that is to be too is why I am hostile to anti-essentialist critiques; it is not t~at defined, is never addressed: namely, should this knowledge affect I think that they are intrinsically mistaken, as that they mis those values and tastes, and if so, how? I ask, in "Aesthetic In construe much of what is really going on in aesthetics. Here, for strumentalism," what sort of understanding is to be had of our example, what matters is not the definition of art but the search selves through the social sciences, but the philosophical question for ideals. 1 0 Introduction Introduction 1 I is better formulated: how is that knowledge to be squared with terms of their intrinsic interest but, deplorably, in terms of other sorts of knowledge, including knowledge of our preferences whether they are in fashion, up to the minute, or this month's and values, that we have about ourselves? . flavor. It is bad enough to have to suffer the swings of fashion in I have long admired R. G. Collingwood as one of the great: if other fields and disciplines, but in philosophy it is outrageous relatively neglected, British philosophers, and have been consid that the date when something was written or published can be erably influenced by all his work, not merely by his work in ae~ supposed to be of any philosophical interest. thetics. In "Morality and Literary Criticism," I suggest there is To be a student of ethics at that time, then, was primarily to one strand in ethics outside the two dominant traditions in west be anti-cognitivist about value judgments, along the lines either of ern moral philosophy-ethics as character and ethics as duty: the emotiVists or prescriptivists who, notwithstanding their dif namely Spinoza's Ethics. This, I claim, was given renewed .atten ferences, were united upon certain points: that is, in a certain tion by Collingwood, particularly in his doctrine, set out i~ T~e reading of G.E. Moore's Principia Ethica, and in the belief that Principles of Art, of the corruption of consciousness, which is value judgments do not have truth-values. My interest was di much closer to the literary critic's talk of insincerity, inauthen verted into aesthetics by a tutor who, knowing that I was also a ticity, and untruthful living than anything one was likely to h~ar student of literature, remarked that plenty of people were work in a university department of philosophy. This talk has about it a ing on the value judgment in ethics but few were doing so in aes Kierkegaardian ring which begins to parallel the religious burden thetics. I discovered subsequently, of course, that much of the many critics have sought to make the term :moral" c~rry. In best work in aesthetics in the very fruitful period we have had Chapter Ten, "Art and Goodness: Collingwood s ~estheti~s and s.ince the early 1960s has explicitly rejected the idea of any par Moore's Ethics Compared," I come back to Collingwood s doc ticular relationship between aesthetics and ethics notwithstand trine of the corruption of consciousness. ing Wittgenstein's remark mentioned above. I was interested in ethics before I became interested in aes I don't myself follow Goodman and others in the expulsion thetics, in which it is surprising that I managed to develop any from or playing down of the issue of evaluation in aesthetics. (Al interest, since the first work I read in aesthetics was a singularly though on the other point, that is, that a student of literature is dreary introduction. Only later, of course, did I h~ar of John ~ell placed to study aesthetics, I now think, on the contrary, that Passmore's famous-and often cited-charge of dreanness. m many ways literature is too peculiar an art, too anomalous as To be interested in ethics when I was an undergraduate in the late 1950s meant primarily to be under the influence of and art, to be the best way into aesthetics.) This is a point I discuss among others in Chapter Nine, "The Perception of Literature." in debt to such philosophers as Charles Stevenson, Richard But the main question which prompted the argument of this Hare, J.O. Urmson, and A.J. Ayer, to name the most prominent chapter is by what senses is a literary work perceived. This will that a student was likely and indeed fortunate to encounter. I undoubtedly seem an odd question to ask. Yet I found it forced stress these points for two reasons. First, although since that upon me when I came to consider the implications for literature time philosophy has moved on, of course, to other writers and of quite standard. traditional accounts of aesthetic experience. other issues, the body of work to which I was first introduced in Given my starting point in ethics, in the study of which I ethics has had a decisive influence on most of the essays in this was taught to analyze "the moral judgment," I naturally book, perhaps most of all when I have been in conscious opposi searched, when working on my Ph.D. thesis in aesthetics tion to that tradition. Second, I want to record my debt to that "Works of Art and Aesthetic Judgements," for "the aestheti~ work here as a protest against the unfortunately growing ten judgment." The search itself was as to its main object somewhat dency in academic philosophy to regard issues and writers not in fruitless, a point I allude to and begin from in my very first Introduction 1 3 Introduction 12 aesthetic) against physicalist reductionism. This point is made published paper, "Evaluation and Aesthetic Appraisals," near the end of Chapter Twelve, "Evaluation and Aesthetic published here as Chapter Twelve. But the inquiry into aesthetic Appraisals." Now, as I suggest in Chapter Seven "Art and judgments, under the influence of what I presumed to be and ~eaning," attempts to eliminate the aesthetic come from a very discovered not to be the parallel inquiry into moral judgment, did different quarter: namely, from the post-Structuralists. lead me into considering a number of questions and topics not . . Pos:~structuralism makes the mistake of confusing the in necessarily in thrall to the nature of aesthetic judgment, which elimma?ility. of the aesthetic with the privileging or valortzing of it. over the years got written up in papers which now appear as In my view, if we seek to deny or eliminate the aesthetic, then un chapters of this volume. d~r~tanding and insight are the casualties, not power and class I begin "Evaluation and Aesthetic Appraisals" with a version pnvilege. On my a priori view (or prejudice) such reductionism is of the "Euthyphro" problem, which is designed to show that i~po~sibl.e, for if the aesthetic is denied, it simply re-appears in emotivism is inapplicable to aesthetics. The problem in its theo disgUise m unacknowledged form. However, it is consistent to logical form is this: is a thing good because God approves it, or hold my view of the ineliminability of the aesthetic without en does God approve of it because it is good? Translated into aes dorsing the aesthetic, whatever that may mean, just as Kant thetics, this becomes the question: "Is something beautiful be could be critical of metaphysics while holding that the h · d. uman cause we admire it, or do we admire it because it is beautiful?". In mm is ineliminably attracted to it. Chapter Ten, "Art and Goodness," I come back to this question In Chapter Fourteen, "Aesthetics and Aesthetic Education (without resolving it), a question which is as crucial to aesthetics (and Mayb.e Morals Too)," I continue with the thought, begun in as it is in a suitably amended form in the realist/anti-realist the .p~ecedmg chapter, "The Evaluation of a Work of Art," that the debates in contemporary ethics. position or role of the spectator is somewhat problematic. I sug I conclude "Art and Goodness" with some comments on gest that in some of the best contemporary work in aesthetics a how G.E. Moore's account of goodness as a non-natural property protest is made ~g~nst the domination of aesthetic theory by might serve as some kind of model or analog for a Minimalist the spectator, while m "The Evaluation of a Work of Art: the Prob work of art. I explore the subject of Minimalism further in Chap lem of M~alism" I suggested that certain forms of contempo ter Thirteen, "The Evaluation of a Work of Art: The Problem of rary art dislodge and make little provision for the spectator. Minimalism." Minimalism provides a useful case for reflecting on In "Ae~thetics ':111d Aesthetic Education" I also continue my the question, implicit in many of my papers, of how art and the preoccupation, manifested in Chapter Eleven, "Aesthetic Instru aesthetic are to be distinguished and related. Indeed, this worry mentalism," with the distinction as it concerns aesthetics be is there from the very beginning, surfacing in my first paper, tween intrinsic and instrumental values. The "aesthetic" is often "Evaluation and Aesthetic Appraisals," albeit in a somewhat tacit associate~ or more closely related to notions of intrinsic good. In and indirect manner, which Bohdan Dziemidok rightly sees as 11 Chapter Fifteen, "The Idea of Aesthetic Experience," I am however typifying the treatment of this issue in recent aesthetics. mar~ .concerne~ with the question of how, if at all, we may use I claim in Chapter Seven, "Art and Meaning," that meaning tradit10nal not.10~s of aesthetic experience in developing an ac and value are ineliminable from the discourse of art and from the count of what .it is to .experience a work of art (thus widening the very idea of art. The ineliminability of the aesthetic has been one question considered m Chapter Nine solely in relation to litera of the motivating convictions of all my work in aesthetics. When I ture to include all the arts). wrote my thesis it seemed most urgent, given the then still pre In Chapter Fifteen I report having found some mismatch vailing positivist philosophical climate, to defend art (not then between the experience of art on the one hand and the experience attending with sufficient care to distinctions between art and the 14 Introduction Introduction 15 of the aesthetic on the other, and suggest that the aesthetic If this book says less about that subject than I would now reaches beyond art in ways that we have not fully addressed or wish, this serves merely to confirm my view of philosophy, a view articulated in Philosophy, and this because our language, includ not original or in any way striking but. none the less and for all ing here the vocabulary of aesthetics, reaches ahead of our that, I think still true. Philosophy then is a process of discovery explicit or conceptuai understanding. A task of philosophy is to or a journey in which the prospect just ahead is always more ur make explicit what is implicit in language. gently demanding of our attention than the ground already William Elton's anthology, Aesthetics and Language.12 covered; but there is the hope too that the journey already made exerted a great influence upon me when I was writing my doctoral is not of purely personal or local interest because the journey is thesis and first Paper, "Evaluation and Aesthetic Appraisals," one of such interest that it is not unreasonable to suppose that which appears here as Chapter Twelve. And I was especially influ others are making it too. It is in this company that I hope to find enced by one of the essays which Elton reprints, Stuart Hamp my readers. shire's "Logic anct Appreciation," a paper which I have recently reconsidered anct attempted some critical reply to in Chapter Sixteen, "Schopenhauer's Account of Aesthetic Experience." More generauy, 1 try to show what problems which a deeply rooted and attractive view of the aesthetic such as Schopen hauer's is has stored up for us in contemporary aesthetics. I claim that our inhertted notions of the aesthetic, such as those deriving from Schopenhauer, have lost whatever metaphysical and in a broad sense religious underpinning they once had, and now have to operate within secular societies and secular views of culture. The implications of our post-Enlightenment secular outlook for aesthetics is a matter I come back to in my final chapter. "Natural Beauty Without Metaphysics" (Chapter Eighteen). This is one of the few chapters in the book not to have art as its subject; rather, I take here what in any case is my first love, the beauty of nature, although-and this is one of the concerns of the chapter-the "beauty of nature" is a somewhat embarrassing phrase for a Professional philosopher, or perhaps intellectuals more generally, to be caught using. Not of course that art is en tirely dispensed With in the argument set out in Chapter Eighteen, but rather is used as a foil against which to try to get some grip on What I treat as the correlative idea of natural beauty. In going back I hope too that I am going forward, in the sense that I see the argu111ents in this chapter as leading me into what, in any case and for obvious reasons, is the growing interest in the aesthetics of the environment. •t Chapter One ESSENTIALISM AND THE DEFINITION OF "ART" I It is commonly believed that a certain kind of attempt to define "art" or "work of art" (I shall use these terms interchangeably) is mistaken. I have in mind the view that to defme "art" in a certain kind of way is to commit the essentialist fallacy. For ease of refer ence I shall describe those who hold this view as the anti-essen tialists. Anti-essentialist arguments are to be found for example in articles by W.B. Gallie, Morris Weitz, and William Kennick. t The term "essentialist fallacy" denotes a cluster of errors. First there is that of presupposing "whenever we are in a position to defme a substance or activity we must know its essence or ulti mate nature-and know this by methods that are entirely differ ent from those used in the experimental and mathematical sciences or in our common-sense judgements about minds and material things. "2 Second. our use of an "abstract word such as 'Art' does not necessarily imply something common to all the ob jects we apply it to. "3 As William Elton put it, "the presence of a substantive is no guarantee that a single substance exists to cor respond with it. "4 It is natural to think there must be something common to all works of art or else we should not call them all by the same name,5 but nevertheless we must avoid this "disastrous interpretation of 'art' as a name for some specifiable class of ob jects. "6 Finally, "Art ... has no set of necessary and sufficient prop erties, hence a theory of it is logically impossible."7 I shall argue that the position I have just outlined may be correct but not for the reasons anti-essentialists generally give. Mine is not the first attempt to criticize the arguments of the