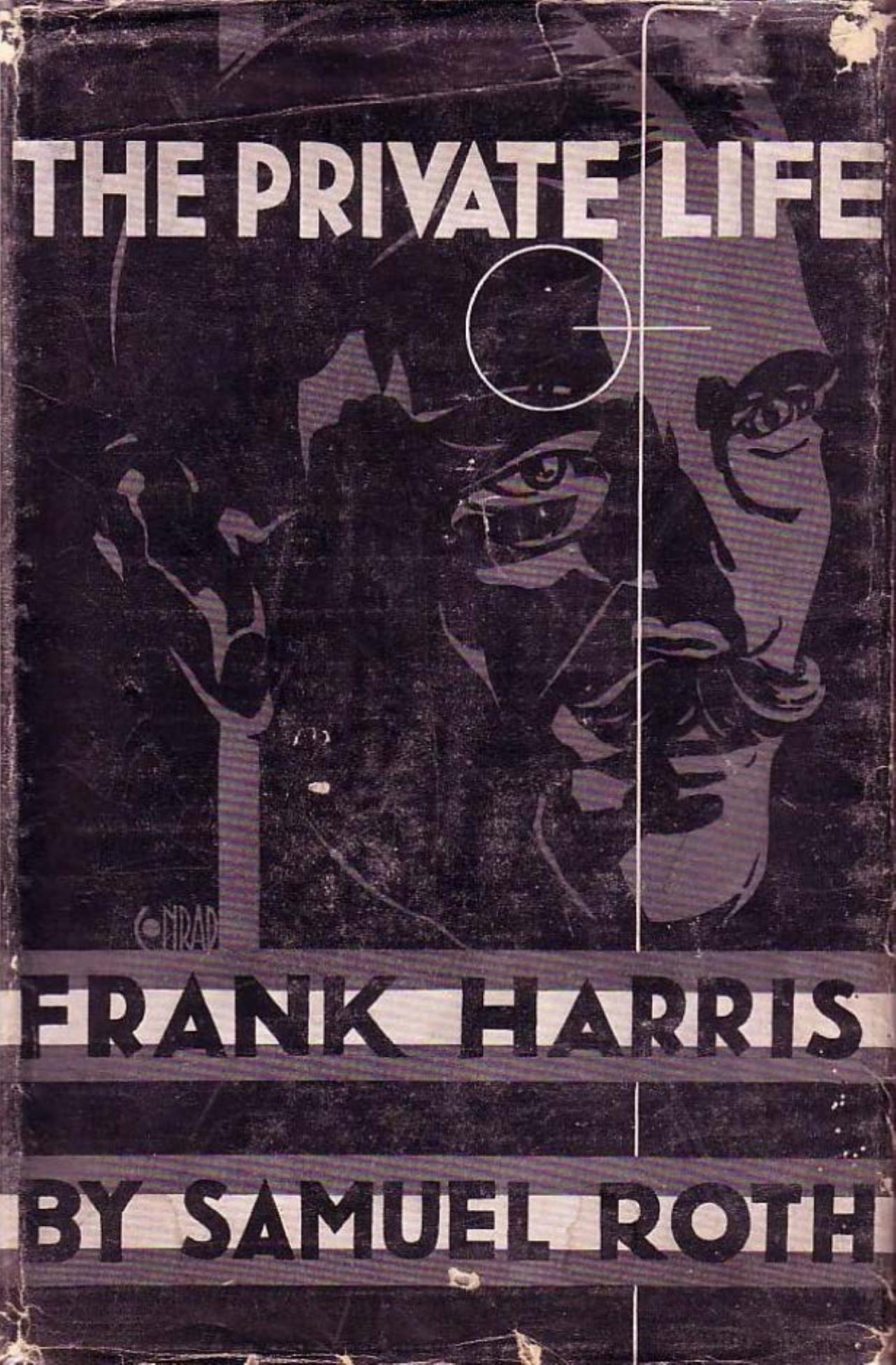

The Private Life of Frank Harris PDF

Preview The Private Life of Frank Harris

Of all the biographies of Harris this is probably the most worthless; worse, even than Evergreen Adventurer. Though it is better-written than Linda Morgan Bain's schoolgirlish fantasy of Harris' life, Roth's wild disregard for the truth places it in a class of its own.

It opens with an account of how Roth met Harris, when in 1919 a man (unnamed by Roth but probably Guido Bruno, to judge by the description given of his resemblance to Oscar Wilde)

brought Harris to Roth's bookshop in Greenwich Village. According to

Roth for a while thereafter they were friends, but lost touch when Roth

moved to London to avoid his creditors; then when Roth returned to New

York he found that Harris had gone to France. Some four years later the

first volume of My Life and Loves

appeared. Roth describes it as 'layers and underlayers of incredible

rubbish' which led him to think Harris had 'gone out of his mind'. He

had to discover 'the truth ... from people who knew Harris'. It would

take 'much, much time'. But what he found, he thought 'makes a great

story'.

'A great example of brazen chutzpah', is likely to be one's reaction on

reading further, given that Roth has just told us how awful Harris' book

is. His first few chapters will engender a curious sense of déjà vu in

anyone who has read My Life and Loves,

as they are no more than a blatent, unacknowledged, rewrite of the most

notable episodes from Harris' own version of his early life: the

schoolboy, the bootblack, the hotel clerk, the cowboy, the law student,

the schoolmaster.

Once he has got Harris to London and established as a journalist, Roth

permits himself to lift his material from other books: from the Contemporary Portraits, from Oscar Wilde and, more openly, from Hesketh Pearson's Modern Men and Mummers.

An indication of the depth of his research is that he describes Harris'

imprisonment for contempt, which is referred to in passing by Pearson,

as a 'mysterious matter'. Anyone who knew of Harris in London at the

time could have enlightened him.

Where his reading leaves gaps in Harris' life, Roth is happy to invent

details. For example, he claims that Harris had 'met and married' Nellie

in about 1914, whereas he had been living with her since before 1900

and did not marry her until 1927. What is more amazing is his ability,

given that he admits he never spoke to Harris after 1919, to know what

Harris was thinking, for example, when he chose Nice as his home: 'He

must leave America. But where should he go? Ireland? His nose wrinkled

disgust. Not for a cultivated Englishman: such he held himself to be.

Pigs and poverty and potatoes, riots and rude ribaldries...'

But it is with the history of My Life and Loves

that Roth finally takes off into the realms of fiction. A mysterious

American publisher with 'an overtone of tiny horns and unseen hooves and

a faint whiff of Gehenna' persuades Harris to write his life as

pornography, to incense the puritans and make lots of money at the same

time. Harris, who until then had planned a conventional autobiography,

is inspired by the publisher's enthusiasm and sets to work.

Harris' brilliant idea, as he explains to 'a retired colonel from the

Indian service', is to make the book 'a colossal josh' full of racy

anecdotes taken from all over and retold with Harris as protagonist. And

more, he'd put in every perversity known: 'In this book he'd have

revulsion from nothing. Necrophilia. Ferophilia, Coprophilia, he would

be panphilic. What a book!'

What a book, indeed: certainly nothing like My Life and Loves

as published. Why Roth, who was obviously very familiar with the actual

content of Harris' suppressed work, should have chosen to exaggerate

its licentiousness like this is not clear. That he had a sincere dislike

of frankness in sexual description would not seem likely, given Roth's

record of publishing and distributing explicit material. Anger at Harris

seems a more likely motive, though we can only guess at its basis -

perhaps the fact that he was left out of Harris' story of his life? A

cynic might also suspect that by playing up the smut content, Roth hoped

to shift a few more copies of it from his under-the-counter stock.

Roth's account of the post-publication failure of My Life and Loves,

though factually highly inaccurate, does at least succeed in capturing

the spirit of what happened, with an unhappy Harris being ripped-off and

persecuted at every turn.

Then Roth presents us with Harris making an entirely imaginary last

visit to England, evidently written with a street map of London open in

front of him, in which Harris wanders around aimlessly on his own for a

day through most of the central areas of the city. (Roth's lack of

equivocation in identifying not just Harris' route but his stray

thoughts along the way is uncanny: even the most half-asleep reader must

wonder where he obtained his information.) Finally, Harris collapses in

a hotel bedroom. Shaw comes to hear of his plight and, taking pity on him, suggests that Harris should write his biography.

Roth continues his incredible mind-reading act into the final chapter where the dying Harris works on his life of Shaw,

while musing on death, his past adventures, and his favourite foods.

Roth even knows that Harris had a vision of his long-dead mother's smile

on his deathbed. What a book! What an author!

Selected editions

Publisher

William Faro

Year

1931

Country

US