The Man Who Climbs Trees PDF

Preview The Man Who Climbs Trees

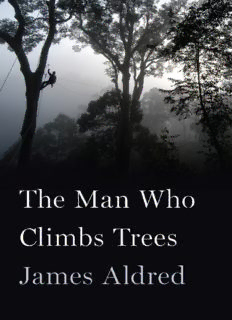

Contents Title Page Contents Copyright Dedication Epigraph Beginnings How I Got Here Goliath—England Tumparak—Borneo Apollo—The Congo Photos Tree of Life—Costa Rica Castaña—Peru Roaring Meg—Australia Ebana—Gabon Kayu Besi—Papua Fortaleza—Venezuela Idyll—Morocco New Forest—England Acknowledgments About the Author Connect with HMH Copyright © 2017 by James Aldred First U.S. edition First published in the UK by W H Allen, an imprint of Ebury Publishing All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016. Except where otherwise indicated, all photographs are © James Aldred. hmhco.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Aldred, James (Tree climber), author. Title: The man who climbs trees / James Aldred. Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018. Identifiers: LCCN 2018005336 (print) | LCCN 2017046397 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328473530 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328473059 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Aldred, James (Tree climber) | British Broadcasting Corporation—Officials and employees—Biography. | Tree climbing. | Television camera operators—Great Britain—Biography. Classification: LCC SB435.85 (print) | LCC SB435.85 .A43 2018 (ebook) | DDC 634.9092 [B]—DC23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018005336 Cover design by Brian Moore Cover photograph © Cede Prudente Author photograph © Fábio Nascimento v1.0418 For you, Yogita, Mera pehla, mera aakhree, mera sachcha pyaar Never before had he been so suddenly and so keenly aware of the feel and texture of a tree’s skin and of the life within it. He felt a delight in the wood and the touch of it, neither as forester nor as carpenter; it was the delight of the living tree itself. —J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings Trees are poems that the earth writes upon the sky. —Kahlil Gibran, Sand and Foam P R O L O G U E Beginnings 1988 THE BOG sucked at my left boot, pulling me off balance. Straightaway, I could feel the earthy soup seep in through the lace holes. I spied a solid tussock of grass ahead of me and pitched myself onto it. Stretching up to grab an overhanging branch, I dragged my leg free, hauled myself forward, and crawled across to solid ground. I was back in the woodland, the bone-dry leaf litter sticking to the black, muddy glue on my legs. Treacherous bogs are a real specialty of the New Forest. Earlier that day I’d placed my foot on seemingly solid ground, only to feel it wobble and bounce like the thin hull of a rubber dinghy. If you break through the mat of moss and weed on the surface of a blanket bog, you can be up to your neck in seconds. I’d already seen plenty of green-stained animal bones jutting out of these mires—a gruesome reminder to give them a wide berth. But at thirteen years old I was still learning how to read the landscape, and impatience sometimes got the better of me. I took a deep breath and wiped off my hands. Next time, I wouldn’t resent taking an extra ten minutes to walk around a bog, that was for sure. I pulled out my map: Stinking Edge Wood. It figured. As I sat down to clean the gunk from between my toes with a sock, distant heavy thuds and the sharp crack of branches echoed through the forest. I had been following a herd of fallow deer, but these noises were too violent and big to be coming from them. Tugging my boot back on, I started slowly forward through the trees. The ground was littered with huge dead branches dropped from the dense canopy above. The afternoon sun streamed into the open space between the trees, and a thin veil of dust hung in the air. The thuds were louder now and I could hear whinnying. A low drumbeat shook the ground briefly before a long stream of ponies came barreling out of the trees toward me. A dozen mares with nostrils flared, their long manes wild and ragged with tangled bracken. and ragged with tangled bracken. There was a crazed excitement to them, a dangerous energy in the air. They galloped around in a spiral to face inward, and beyond them I could see two white stallions reeling together in a violent storm of teeth, hooves, and spittle. Eyes rolling, pink nostrils open wide, lips curled back to expose savage teeth. They bucked, kicked, and reared to land heavy blows on one another with their hooves. The mares were almost screaming with excitement, giving out long intense whinnies. The ground shook again, and it suddenly struck me that despite being so close, the whole herd was still completely oblivious to me. The air was thick with their pungent smell, and I was in very serious danger of getting caught up in the fray, overrun, and trampled. I suddenly panicked, realizing I had only moments to find somewhere to hide. The mares were running again—circling the two stallions in wild flurries and closing fast. I couldn’t outrun them. Stepping back, I felt a tree trunk behind me. A big oak, but there were too many ponies for it to offer any real protection. Its first branch was out of reach high above, and my heart raced as my legs began to shake. Desperately running my hands along its rough bark, I felt an ancient iron peg jutting out of the trunk. It had been there so long, the tree had almost engulfed it, but there was just enough still protruding to grip. Above it I found a second, then a third, fourth, and fifth—and before I knew it, I was lying flat on my stomach on a wide branch, looking straight down onto the muscular backs of the stallions roiling five feet below. The oak and I were at the center of a swirling mass of ponies beside themselves in a weltering frenzy. Dust and noise filled the air, and I was gripping the corrugated bark hard, my head spinning and my heart racing as adrenaline coursed through me. One of the stallions broke away and the herd rolled after him through the trees. I listened as the drumming of hooves on dry earth faded, and I took another deep breath in gratitude for being given such a timely escape. Silence returned to the forest and the dust began to settle. Looking at the branches around me, I could see that I was sitting in an ancient oak pollard. The iron pegs were testimony that someone, perhaps a forest keeper, verderer, or even poacher, had used it regularly many years ago. Perhaps it had been a lookout, or a place to hide long before I had sought refuge there myself. The wide horizontal branches stretched away from me to curl up like the giant fingers of an enormous cupped hand. I slid back into the center of its protective palm and waited for my heart to slow. After a while the small herd of fallow deer I had been following emerged from the trees, carefully picking their way through the churned-up leaf litter to pass beneath me in the wake of the ponies. They had been there all along, and I was immediately struck that not one of them appeared to have seen or smelled me as I crouched in the arms of the oak directly above. The relief I felt, once in the branches of that tree, had been immediate. I had instantly known I was safe from the violent turmoil below, and seeing the fallow deer pass by had only reinforced my feeling of sanctuary and removal. But beyond that, I also felt an ancient connection to whoever had placed those iron pegs and sat in these same branches where I was now sitting, as if the intervening time had collapsed completely. I’ve revisited that same oak on the edge of Stinking Edge Wood many times since. Those iron pegs are a tangible reminder that trees inhabit a different timescale than we do and that the life of one tree can easily span dozens of human generations. Climbing up into its giant arms always takes me back to that exciting day in 1988 when as a thirteen-year-old boy I first discovered that trees were places of refuge and offered new vantage points from which to view our world. Even now, almost thirty years later, I still find myself puzzling over the way it just happened to be there for me. In the right place at the right time, when I had needed it most.

Description: