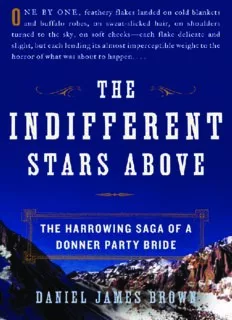

The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of a Donner Party Bride PDF

Preview The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of a Donner Party Bride

For Sharon Thank you And they had nailed the boards above her face, The peasants of that land, Wondering to lay her in that solitude, And raised above her mound A cross they had made out of two bits of wood, And planted cypress round; And left her to the indifferent stars above. —W. B. Yeats, “A Dream of Death” Contents Epigraph iii Author’s Note vii Prologue 1 Part One: A Sprightly Boy and a Romping Girl 7 Chapter One Home and Heart 9 Chapter Two Mud and Merchandise 25 Chapter Three Grass 45 Part Two: The Barren Earth 59 Chapter Four Dust 61 Chapter Five Deception 76 Chapter Six Salt, Sage, and Blood 93 Part Three: The Meager by the Meager Were Devoured 117 Chapter Seven Cold Calculations 119 Chapter Eight Desperation 140 Chapter Nine Christmas Feasts 159 Chapter Ten The Heart on the Mountain 176 Chapter Eleven Madness 189 Chapter Twelve Hope and Despair 204 Photographic Insert Chapter Thirteen Heroes and Scoundrels 222 vi Contents Part Four: In the Reproof of Chance 243 Chapter Fourteen Shattered Souls 245 Chapter Fifteen Golden Hills, Black Oaks 256 Chapter Sixteen Peace 264 Chapter Seventeen In the Years Beyond 267 Epilogue 274 Appendix: The Donner Party Encampments 289 Acknowledgments 293 Chapter Notes 295 Sources 325 About the Author Other Books by Daniel James Brown Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Author’s Note Even well after the tragedy was over, Sarah Graves’s little sister Nancy often burst into tears for no apparent reason. She mysti fied many of her schoolmates in the new American settlement at the Pueblo de San José. One minute she would be fine, running, laughing, and playing on the dusty school ground like any other ten- or eleven- year-old, but then suddenly the next minute she would be sobbing. All of them knew that she had been part of what was then called the “lamentable Donner Party” while coming overland to California in 1846. Recent emigrants themselves, most of them knew, generally, what that meant and sympathized with her for it. But for a long while, none of them knew Nancy’s particular, individual secret. That part was just too terrible to tell. Nancy Graves’s secret was just one part of many things that were too terrible to tell by the time the last survivors of the Donner Party staggered out of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the spring of 1847. And for decades thereafter, many of those things were not told, ex cept in tabloid newspaper accounts that were often compounded far viii Au t hor’s No t e more of fiction than of truth. It wasn’t until a newspaper editor named Charles F. McGlashan began to delve into the story in the 1870s that many of the real details of what had happened that winter in the Si erra Nevada started to emerge. McGlashan set about interviewing survivors, and in 1879 he published his History of the Donner Party, the first serious attempt at documenting the disaster. Since then the true stories and the fictional ones have bred and interbred in the Amer ican imagination. In introducing his recent book, Patriot Battles: How the War of Independence Was Fought, Michael Stephenson points out that our ideas about the generation that fought the American Revolution have become “embalmed” by “the slow accretion of national mythology.” How true. I still cannot think of George Washington without visual izing him as a marble bust. But if the generation of 1776 has been fos silized by mythology, the same is equally true of their grandchildren. The emigrant generation of the 1840s has been endlessly depicted in film and television productions, almost always in highly stereotyped ways—a string of clichés about strong-jawed men circling the wagons to hold off Indian attacks and hard-edged women endlessly churning butter and peering out from under sunbonnets with eyes as cold and hard as river-worn stones. The emigrants of the 1840s deserve better. They were, on the whole, a remarkable people living in remarkable times. Just how remarkable they were has largely been camouflaged for us, not only by the stereo typing and the mythologizing but by the homespun ordinariness of their clothes, the commonplace nature of their language, the simple virtues they held dear, and the casual courage with which they con fronted long odds and bitterly harsh realities. The men among them did, in fact, sometimes circle their wagons to defend against potential Indian attacks, though the attacks were anticipated far more often than they ever occurred. But the men also lay awake at night agonizing about what they had gotten their families into, schemed to take advan tage of one another, sobbed under the stars when their children died, lusted after women half their ages. And the women did, of course, churn a great deal of butter, but they also studied botany, counseled troubled teenagers, yearned for love, struggled with domineering Aut hor’s Not e ix husbands, and made wild rollicking love deep in the recesses of their covered wagons. Like all people in all times, the emigrant men and women, as well as the Native American men and women, of the 1840s were complex bundles of fear and hope, greed and generosity, nobility and savagery. And in the end, each of them was, of course, an individual, as unique and vital and finely nuanced as you or me. So before I began to write this book, I made a vow to myself that wherever possible I would cut through the clichés and resist the easy assumptions about the men and women who went west in 1846. And I decided that I would focus on one woman in particular, Sarah Graves, and tell the unvarnished truth about what happened to her in the high Sierra in the terrible winter of that year. Sarah hasn’t made it easy. She left little record of her own experi ences, and while others who suffered through the ordeal with her that winter have left us with their own, sometimes quite detailed accounts, few of them have had much to say about her. But what accounts there are suggest that she was a friendly, sociable, and thoughtful person, well liked by many of her companions but perhaps not apt to call at tention to herself. And so while I have everywhere tried to remain entirely factual in writing about her, I have at times extrapolated from what those who accompanied her reported or from the published findings of experts in particular fields to describe what she must have experienced. Knowing, for instance, that she spent a specific night sleeping on the snow, clad only in wet flannel as the mercury plum meted into the low twenties, allows us also to know with reasonable certainty what she must have experienced in terms of physical dis comfort, potential hypothermia, and psychological distress. So I have gone where eyewitness accounts and expert testimony have led me in describing such experiences. Similarly, in places I have drawn on my own experiences walking in her footsteps to re-create direct physical sensations that she must inevitably have felt. So, for example, in de scribing her passage through tall prairie grass, I have included sensory details from my own trek through the deep grass of the Willa Cather Memorial Prairie in Nebraska. With that in mind, I offer this book not as a comprehensive history

Description: