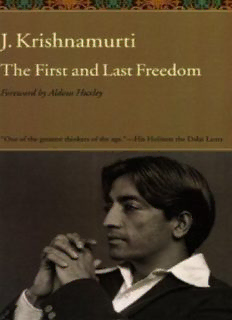

The First and Last Freedom PDF

Preview The First and Last Freedom

The First and Last Freedom Copyright © 1954 by Krishnamurti Foundation of America T H E F I R S T A N D L A S T F R E E D O M by J . K R I S H N A M U R T I with a foreword by ALDOUS HUXLEY CONTENTS Foreword by Aldous Huxley I. Introduction II. What are we seeking? III. Individual and Society IV. Self-knowledge V. Action and Idea VI. Belief VII. Effort VIII. Contradiction IX. What is the Self? X. Fear XI. Simplicity XII. Awareness XIII. Desire XIV. Relationship and Isolation XV. The Thinker and the Thought XVI. Can Thinking solve our Problems? XVII. The Function of the Mind XVIII. Self-deception XIX. Self-centred Activity XX. Time and Transformation XXI. Power and Realization QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS 1. On the present Crisis 2. On Nationalism 3. Why Spiritual Teachers? 4. On Knowledge 5. On Discipline 6. On Loneliness 7. On Suffering 8. On Awareness 9. On Relationship 10. On War 11. On Fear 12. On Boredom and Interest 13. On Hate 14. On Gossip 15. On Criticism 16. On Belief in God 17. On Memory 18. Surrender to ‘What Is’ 19. On Prayer and Meditation 20. On the Conscious and Unconscious Mind 21. On Sex 22. On Love 23. On Death 24. On Time 25. On Action without Idea 26. On the Old and the New 27. On Naming 28. On the Known and the Unknown 29. Truth and Lie 30. On God 31. On Immediate Realization 32. On Simplicity 33. On Superficiality 34. On Triviality 35. On the Stillness of the Mind 36. On the Meaning of Life 37. On the Confusion of the Mind 38. On Transformation FOREWORD Man is an amphibian who lives simultaneously in two worlds—the given and the home-made, the world of matter, life and consciousness and the world of symbols. In our thinking we make use of a great variety of symbol-systems— linguistic, mathematical, pictorial, musical, ritualistic. Without such symbol- systems we should have no art, no science, no law, no philosophy, not so much as the rudiments of civilization: in other words, we should be animals. Symbols, then, are indispensable. But symbols—as the history of our own and every other age makes so abundantly clear—can also be fatal. Consider, for example, the domain of science on the one hand, the domain of politics and religion on the other. Thinking in terms of, and acting in response to, one set of symbols, we have come, in some small measure, to understand and control the elementary forces of nature. Thinking in terms of, and acting in response to, another set of symbols, we use these forces as instruments of mass murder and collective suicide. In the first case the explanatory symbols were well chosen, carefully analysed and progressively adapted to the emergent facts of physical existence. In the second case symbols originally ill-chosen were never subjected to thoroughgoing analysis and never reformulated so as to harmonize with the emergent facts of human existence. Worse still, these misleading symbols were everywhere treated with a wholly unwarranted respect, as though, in some mysterious way, they were more real than the realities to which they referred. In the contexts of religion and politics, words are not regarded as standing, rather inadequately, for things and events; on the contrary, things and events are regarded as particular illustrations of words. Up to the present symbols have been used realistically only in those fields which we do not feel to be supremely important. In every situation involving our deeper impulses we have insisted on using symbols, not merely unrealistically, but idolatrously, even insanely. The result is that we have been able to commit, in cold blood and over long periods of time, acts of which the brutes are capable only for brief moments and at the frantic height of rage, desire or fear. Because they use and worship symbols, men can become idealists; and, being idealists, they can transform the animal’s intermittent greed into the grandiose imperialisms of a Rhodes or a J. P. Morgan; the animal’s intermittent love of bullying into Stalinism or the Spanish Inquisition; the animal’s intermittent attachment to its territory into the calculated frenzies of nationalism. Happily, they can also transform the animal’s intermittent kindliness into the lifelong charity of an Elizabeth Fry or a Vincent de Paul; the animal’s intermittent devotion to its mate and its young into that reasoned and persistent cooperation which, up to the present, has proved strong enough to save the world from the consequences of the other, the disastrous kind of idealism. Will it go on being able to save the world? The question cannot be answered. All we can say is that, with the idealists of nationalism holding the A-bomb, the odds in favour of the idealists of cooperation and charity have sharply declined. Even the best cookery book is no substitute for even the worst dinner. The fact seems sufficiently obvious. And yet, throughout the ages, the most profound philosophers, the most learned and acute theologians have constantly fallen into the error of identifying their purely verbal constructions with facts, or into the yet more enormous error of imagining that symbols are somehow more real than what they stand for. Their word-worship did not go without protest. “Only the spirit,” said St. Paul, “gives life; the letter kills.” “And why,” asks Eckhart, “why do you prate of God? Whatever you say of God is untrue.” At the other end of the world the author of one of the Mahayana sutras affirmed that “the truth was never preached by the Buddha, seeing that you have to realize it within yourself”. Such utterances were felt to be profoundly subversive, and respectable people ignored them. The strange idolatrous overestimation of words and emblems continued unchecked. Religions declined; but the old habit of formulating creeds and imposing belief in dogmas persisted even among the atheists. In recent years logicians and semanticists have carried out a very thorough analysis of the symbols, in terms of which men do their thinking. Linguistics has become a science, and one may even study a subject to which the late Benjamin Whorf gave the name of metalinguistics. All this is greatly to the good; but it is not enough. Logic and semantics, linguistics and metalinguistics—these are purely intellectual disciplines. They analyse the various ways, correct and incorrect, meaningful and meaningless, in which words can be related to things, processes and events. But they offer no guidance, in regard to the much more fundamental problem of the relationship of man in his psychophysical totality, on the one hand, and his two worlds, of data and of symbols, on the other. In every region and at every period of history, the problem has been repeatedly solved by individual men and women. Even when they spoke or wrote, these individuals created no systems—for they knew that every system is a standing temptation to take symbols too seriously, to pay more attention to words than to the realities for which the words are supposed to stand. Their aim was never to offer ready-made explanations and panaceas; it was to induce people to diagnose and cure their own ills, to get them to go to the place where man’s problem and its solution present themselves directly to experience. In this volume of selections from the writings and recorded talks of Krishnamurti, the reader will find a clear contemporary statement of the fundamental human problem, together with an invitation to solve it in the only way in which it can be solved—for and by himself. The collective solutions, to which so many so desperately pin their faith, are never adequate. “To understand the misery and confusion that exist within ourselves, and so in the world, we must first find clarity within ourselves, and that clarity comes about through right thinking. This clarity is not to be organized, for it cannot be exchanged with another. Organized group thought is merely repetitive. Clarity is not the result of verbal assertion, but of intense self-awareness and right thinking. Right thinking is not the outcome of or mere cultivation of the intellect, nor is it conformity to pattern, however worthy and noble. Right thinking comes with self-knowledge. Without understanding yourself, you have no basis for thought; without self- knowledge, what you think is not true.” This fundamental theme is developed by Krishnamurti in passage after passage. “There is hope in men, not in society, not in systems, organized religious systems, but in you and in me.” Organized religions, with their mediators, their sacred books, their dogmas, their hierarchies and rituals, offer only a false solution to the basic problem. “When you quote the Bhagavad Gita, or the Bible, or some Chinese Sacred Book, surely you are merely repeating, are you not? And what you are repeating is not the truth. It is a lie; for truth cannot be repeated.” A lie can be extended, propounded and repeated, but not truth; and when you repeat truth, it ceases to be truth, and therefore sacred books are unimportant. It is through self-knowledge, not through belief in somebody else’s symbols, that a man comes to the eternal reality, in which his being is grounded. Belief in the complete adequacy and superlative value of any given symbol- system leads not to liberation, but to history, to more of the same old disasters. “Belief inevitably separates. If you have a belief, or when you seek security in your particular belief, you become separated from those who seek security in some other form of belief. All organized beliefs are based on separation, though they may preach brotherhood.” The man who has successfully solved the problem of his relations with the two worlds of data and symbols, is a man who has no beliefs. With regard to the problems of practical life he entertains a series of working hypotheses, which serve his purposes, but are taken no more seriously than any other kind of tool or instrument. With regard to his fellow beings and to the reality in which they are grounded, he has the direct experiences of love and insight. It is to protect himself from beliefs that Krishnamurti has “not read any sacred literature, neither the Bhagavad Gita nor the Upanishads”. The rest of us do not even read sacred literature; we read our favourite newspapers, magazines and detective stories. This means that we approach the crisis of our times, not with love and insight, but “with formulas, with systems”—and pretty poor formulas and systems at that. But “men of good will should not have formulas; for formulas lead, inevitably, only to “blind thinking”. Addiction to formulas is almost universal. Inevitably so; for “our system of upbringing is based upon what to think, not on how to think”. We are brought up as believing and practising members of some organization—the Communist or the Christian, the Moslem, the Hindu, the Buddhist, the Freudian. Consequently “you respond to the challenge, which is always new, according to an old pattern; and therefore your response has no corresponding validity, newness, freshness. If you respond as a Catholic or a Communist, you are responding—are you not?—according to a patterned thought. Therefore your response has no significance. And has not the Hindu, the Mussulman, the Buddhist, the Christian created this problem? As the new religion is the worship of the State, so the old religion was the worship of an idea.” If you respond to a challenge according to the old conditioning, your response will not enable you to understand the new challenge. Therefore what “one has to do, in order to meet the new challenge, is to strip oneself completely, denude oneself entirely of the background and meet the challenge anew”. In other words symbols should never be raised to the rank of dogmas, nor should any system be regarded as more than a provisional convenience. Belief in formulas and action in accordance with these beliefs cannot bring us to a solution of our problem. “It is only through creative understanding of ourselves that there can be a creative world, a happy world, a world in which ideas do not exist.” A world in which ideas do not exist would be a happy world, because it would be a world without the powerful conditioning forces which compel men to undertake inappropriate action, a world without the hallowed dogmas in terms of which the worst crimes are justified, the greatest follies elaborately rationalized. An education that teaches us not how but what to think is an education that calls for a governing class of pastors and masters. But “the very idea of leading somebody is anti-social and anti-spiritual”. To the man who exercises it, leadership brings gratification of the craving for power; to those who are led, it brings the gratification of the desire for certainty and security. The guru provides a kind of dope. But, it may be asked, “What are you doing? Are you not acting as our guru?” “Surely,” Krishnamurti answers, “I am not acting as your guru, because, first of all, I am not giving you any gratification. I am not telling you what you should do from moment to moment, or from day to day, but I am just pointing out something to you; you can take it or leave it, depending on you, not on me. I do not demand a thing from you, neither your worship, nor your flattery, nor your insults, nor your gods. I say, This is a fact; take it or leave it. And most of you will leave it, for the obvious reason that you do not find gratification in it.” What is it precisely that Krishnamurti offers? What is it that we can take if we wish, but in all probability shall prefer to leave? It is not, as we have seen, a system of beliefs, a catalogue of dogmas, a set of ready-made notions and ideals. It is not leadership, not mediation, not spiritual direction, not even example. It is not ritual, not a church, not a code, not uplift or any form of inspirational twaddle. Is it, perhaps, self-discipline? No; for self-discipline is not, as a matter of brute fact, the way in which our problem can be solved. In order to find the solution, the mind must open itself to reality, must confront the givenness of the outer and inner worlds without preconceptions or restrictions. (God’s service is perfect freedom. Conversely, perfect freedom is the service of God.) In becoming disciplined, the mind undergoes no radical change; it is the old self, but “tethered, held in control”. Self-discipline joins the list of things which Krishnamurti does not offer. Can it be, then, that what he offers is prayer? Again, the reply is in the negative. “Prayer may bring you the answer you seek; but that answer may come from your unconscious, or from the general reservoir, the storehouse of all your demands. The answer is not the still voice of God.” Consider, Krishnamurti goes on, “what happens when you pray. By constant repetition of certain phrases, and by controlling your thoughts, the mind becomes quiet, doesn’t it? At least, the conscious mind becomes quiet. You kneel as the Christians do, or you sit as the Hindus do, and you repeat and repeat, and through that repetition the mind becomes quiet. In that quietness there is the intimation of something. That intimation of something, for which you have prayed, may be from the unconscious, or it may be the response of your memories. But, surely, it is not the voice of reality; for the voice of reality must come to you; it cannot be appealed to, you cannot pray to it. You cannot entice it into your little cage by doing puja,

Description: