The effect of fire on the avifauna of subalpine woodland in the Snowy Mountains PDF

Preview The effect of fire on the avifauna of subalpine woodland in the Snowy Mountains

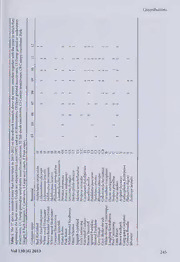

Contributions The effect offire on the avifauna ofsubalpine woodland in the SnowyMountains Ken Green NationalParksandWildlifeService,SnowyMountainsRegion,POBox2228,Jindabyne,NSW2627 Email:[email protected] Abstract TheseasonalchangesinabundanceofbirdspeciesandindividualsinsubalpinewoodlandintheMunyangVal- leywerestudiedfrom2000to2012.Theimmediateresponseoftheavifaunatothefiresof2003wasareduction inthenumberofspecies(from 12to7)andindividuals(by77%).Keytothesereductionswasthelossofforag- ingsubstratesthatdidnotrecoverquickly,suchasshrubsandthetreecanopy,bark,lowerbranchesandleaves. The general response ofthe avifaunawas in contrast to other areas in south-eastern Australia, particularly with theslowerrecoveryofvegetationduetolowgrowthrates andtreesregeneratingfromlignotubertillers rather than epicormicshoots. The Flame Robin Petroicaphoenicea wasthefirst to re-occupythewoodland, withwinterresidentspeciesbeingnexttoreturn.Aftertenyears,thecanopyhadstill notregrown, adversely affectingcanopyforagingspecies,particularlyseedeaters,whilefoodsourcessuchasflowersofGrevillea vic- toriaewerenotavailableinpre-fireamounts,slowingthereturnofhoneyeaters. (TheVictorianNaturalist 130(6) 2013,240-248) Keywords: Snowgum,foraging, treecanopy, Grevillea victoriae Introduction The subalpine zone is that area between the fire. The cambium near ground level is unpro- timberlineandthealpinetreeline(Costin 1954; tected beneath thin bark and thus is generally Korner 2012). It is an area where productivity killed even in relatively cool fires, effectively slowsonanaltitudinaltransectuntiltreesreach ringbarkingthetree.Mostoftheabove-ground theirtemperature-dependentphysiologicallim- biomass subsequently dies and one year after it (Korner 2012). Pre-European fire frequency the widespread wildfire of2003, 96.5% of400 inAustralianhighsubalpinewoodlandwaslow sampled treeshad lost their original leafcover at aboutone majorfirepercentury (Wimbush (Pickering and Barry 2005). Only about 4% of and Forrester 1988; Banks 1989; Dodson et al these trees responded with shooting from the 1994).SinceEuropeansettlement, firehasbeen stem, whereas 95% responded with regenerat- more common but still not achieving the fre- inglignotillers(PickeringandBarry2005).The quency of lower more fire-prone areas. Over means of regeneration, together with inher- thecourseof35daysinJanuary/February2003, entlyslowgrowth ratesathigheraltitudemean wildfires ignitedbylightningburntthroughal- that, following fire, subalpine woodland would most85%(970km2 ofthesubalpineandalpine be expected to take a long time to recover to ) zonesoftheSnowyMountains. Thesefireswere pre-fire condition. However, lackofwoodland the most extensivehigh altitudefires on main- monitoringfollowingprevious firesmeansthat landAustraliasince 1939. recoverytimesarenot available. In lower altitude fire-prone and fire-adapted Such a large landscape scale fire at high landscapes, eucalypts have the ability to re- altitudesasoccurredin2003hasnotpreviously sprout after even intense fires. Unlike most been studied in Australia in relation to its angiosperm trees, Eucalyptus have dormant impact on the fauna. It is fortuitous, therefore, epicormic buds at the level of the vascular that the avifauna ofthe area has been studied cambium where they are insulated beneath overalongperiod. Osborne andGreen (1992) the bark and survive fire, allowing re-shooting examined seasonal changes in abundance from stems and branches within weeks offire of bird species and individuals in subalpine (Burrows 2002). However, thedominant main- woodland. They found that sites in woodland land subalpine woodland species, Snowgum above 1500 m generally had only one or two Eucalyptuspauciflora niphophila is sensitive to species present in winter, rising to about 15 240 TheVictorianNaturalist Contributions species in spring. They defined a number of toprovideameasureofvegetationstructure.At foraging substrates that were regularly used each measurement point the ranging pole was by birds, many of which would be adversely placed vertically through the vegetation to the affectedbyfire.Therehavebeenfewstudiesthat groundatthecentral pointandatadistanceof m havefollowedthecompositional changesofan 3 uphill, downhill and to the left and right avifauna through afireeventfrompre-ignition ofthecentralpoint. Anycontact with apartof mm to the recovery to pre-fire status (Woinarski livevegetationwithina200 intervalonthe andRecher 1997). However,the 10kmtransect polewasrecordedforeachmeasurementpoint, used by Osborne and Green (1992) was being giving a score for each site ofbetween 0 and 5 monitored atthe time ofthe fire (Green 2006) foranygiven heightinterval. andwasinfactwalkedonthemorningthatthe Trees firesbrokeout. The present study was therefore able to fol- Tree height was measured for 30 trees on the lowthe changes in a known avifauna. The aim unburnt transect. Tree heights were calculated ofthe studywasto determine howthe pre-fire usingmeasurementscollectedwitharangefinder and clinometer. On the burnt transect, the avifauna re-established in relation to the veg- etationchangesthataccompaniedtheregrowth height of the highest regenerating lignotiller ofthesubalpinewoodland. wasmmeasured for 10 trees at four altitudes in 50 increments up DisappointmentSpurand Methods foronesiteontheaqueductbench,totalling50 TwowoodlandtransectsintheMunyangValley trees. Heightwas measured usinganextending m (36°20’S, 148°25’E)werestudiedbetween2000 pole (7 long) with tapeattached.Treeheight and 2012 (Fig. 1).One transect (T1-burnt) ran wasmeasuredonthe unburnttransect in 2008 from 1500 m asl up an aqueduct access track and on the burnt transect in 2008 and 2012. on Disappointment Spur (1.5 km) then ran at Treeheightontheburnttransectwasessentially between 1600and 1650 m aslalong theaque- 0m for2003. duct itself(3.0 km). The second transect (T2- Birds unburnt), on the western sideofthe sameval- ley at 2-6 km distance from the first, ran for Depending on weather, the number of bird 2.0kmat 1580maslalonganaqueductbench. species was counted on each transect at Both transects ran through woodland consist- approximately weekly intervals from the end ing mainly ofSnowgum with a canopy up to ofJulytothearrival ofthelast regular migrant about 15 m with thickheath understorey (pre- speciesthrough2003(Fig.2).From2004to2012 fireonlyforone) for muchoftheirlength (Os- the unburnt transect was monitored weekly borneand Green 1992). andatthetimeofmaximalspeciesnumbersthe burnt transect was also monitoredoverone to Vegetation twoweeks. Wherepossible,birdswerecounted For measurements of flowering of the shrub on mornings with calm weather. Bird species Grevillea victoriae, the proportion ofup to 50 present on the transects were identified by haphazardly chosen inflorescences ofG. victo- sight, call, and, in the case ofSuperb Lyrebird riaebearingopen flowerswas recorded ateach Menura novaehollandiae bytracksinsnow. , ofthree siteson theburnttransect and twoon theunburnt. Anaveragewascalculatedforeach Results Vegetation transect (seeGreen 2006fordetails). Understoreyvegetation height and densityin NoflowersofGrevillea victoriaewere recorded woodland recoveringfromfirewasmeasuredat on the burnt transect until fiveyears post-fire 21 sitesatSmiggin Holes (1680 m) sixkilome- in 2008(Fig.3).Evenafterthistime,therewere tressouthofthestudyareawherethevegetation few inflorescences on shrubs and, whereas has been monitored since the 1970s. To deter- usuallya single shrub was sufficient to find 10 minevegetation coverateach site, a3 m rang- sample inflorescenceson theunburnt transect, ingpolemarked at200mm intervals wasused on the burnttransectthree shrubs was usually the minimum requirement. (The total number Vol 130 (6) 2013 241 Contributions Fig. 1. Map ofstudy area. The transects arethedashedlines;T1 (burnt) ranfrom m 1500 asl up an aqueduct accesstrack on Disappointment Spur and along an aqueduct bench at 1600-1650 m, T2 (unburnt) was on an aqueduct bench at 1580monthewesternsideofthevalley. mm ofinflorescences per shrub was not counted). also by 2005. The structure of the veg- The general trend in flowering was no recov- etation recovered more slowly for higher lay- eryuntil2008andthen areducedavailabilityof ers and peaked in 2011 for 800-1000 mm and flowersrelativetotheunburnttransectthrough 1000-1200 mm. The shrub species responsible theremainderofthestudy. for mostofthehigher records was Bossiaeafo- Theheightand densityofshrubsinwoodland liosa, a species that is favoured by fire (Good increased slowly, with nine years elapsing be- 1992), but that may senesce and thin out at fore layers above lm in height became estab- about 15 years (Wimbush and Forrester 1988) lished (Fig. 4). The ground cover <200 mm, withslowergrowingshrubsemergingbeneath. largelygrasses,wasthefirsttorecoverreaching closetothemaximumscoreof5by2005 (note: Trees No epicormic shoots were observed on stems Sthuebrseeqwuaesntnolaymeresa,s2u0r0e-m4e0n0tminm20a0n4d)4(0F0i-g640)0. orbranchesofburnt Snowgumonthetransect. mm reached scores ofbetween 4 and 5 within Initially, post-fire, there were no shoots from 10years, with mostoftherecoveryof200-400 the lignotubers on the burnt transect and so 242 TheVictorianNaturalist Contributions Fig. 2Seasonalchangesinaver- age number ofspecies ofbirds (circles), percentage ofground species clearofsnow(squares)andper- centageofinflorescencesofGre- villea victoriae with open flow- bird ers (triangles) on the unburnt transect from the last week in of Julyto thelastweekofSeptem- ber over 10 years, 2003-2012. (Scaleforflowersisx2.0) Number Fig. 3. Percentage of inflores- cences of Grevillea victoriae flowers withopen flowersatthetimeof maximal bird species numbers on the unburnt western aque- open duct (squares) and at the same time on the burnt transect on with DisappointmentSpur/aqueduct (circles). inflorescences % index Fig. 4. Regrowth ofshrub un- derstorey in subalpine wood- land by layer - each layer is 20 cm deep. Ihemaximum possi- density blescoreforanylayeris5.0(see methods). Diamonds 0-20 cm, squares 20-40 cm, filled circles 40-60 cm, open circles 60-80 Vegetation cm,triangles80-100cm,crosses 100-120cm. Vol 130 (6) 2013 243 Contributions height was scored as zero (see Pickering and then accelerated with nine species in 2007 and Barry 2005) but lignotillers averaged 3.18 m 16 in 2012, bringing the number back within (±0.59 SD) in 2008 and 5.36 m (±0.93 SD) in the pre-fire range (within 1 SD) for the first 2012 (Fig. 5). Thetreesformingthecanopyon time(Fig.6). the unburnt transect averaged 15.97 m (±3.1 Two counts of83 and 88 individual birds on SD). Bark still adhered to most of the burnt the unburnt aqueducton20Septemberand26 trees and peeled offin subsequent years until September2012 gavefiguresof44and45birds by 2012 no dead trees were observed to have km 1. A single count on 27 September on the adheringbark. Disappointment Spur/aqueduct transect gave 55individualbirdsat 12.2birdsperkm. Birds The species ofbirds recorded more than three Discussion times in the study area consisted of15 winter- The transects used by Osborne and Green ing species and 14 spring immigrants (Table (1992) encompassed 10 km of which 6.5 km 1). The numberofbird species on the unburnt was used in the present study. Osborne and transect was about five at the end ofJuly, ris- Green (1992) recordedbetween 17and22 bird ingtoabout 16speciesbytheendofSeptember speciesacrossSeptemberandOctober1982and (5.3 ±4.0 and 16.3 ±2.6; Fig. 2). Forthree years 1983, comparedwithgenerally17to 19species pre-fire the maximum number of species on in the present study on the unburnt transect. the Disappointment Spur/aqueduct transect in Hence,intermsofspecies,theunburnttransect midto lateSeptemberaveraged 17.3 (±3.5 SD) is probably a good representation of the nor- andpost-fire on theunburnt transectaveraged mally unburnt state, except in the two seasons 17.1 (±2.3 SD). Post-fire there were two years immediatelypost-firewhenonly 12and 15spe- oflower than average numbers ofbird species cies were present (Fig. 6) possibly because the ontheunburnttransect,withthenumbersthen wider extent of burning affected the suitabil- risingtowithin therangepre-fireon the burnt ity ofthe general area. On the burnt transect, transect (Fig. 6). There were three species of the immediate response of the avifauna after birdsontheburnttransectinthespringfollow- the 2003 fire was a reduction in the number ingthefirewith littlechangeto 2006 when the ofspecies and individuals (Green and Sanecki number had risen to five. The rate ofincrease 2006). From 12 species counted on the day Year Fig. 5. Heightofthetallestregeneratinglignotillerpost-fireon50treesfromfivelocationsonDisap- pointmentSpurandalongtheaqueductbench.TheequationforthelineandtheR2valueareshown. 244 TheVictorianNaturalist Contributions Contributions the fire commenced on 8 January 2003 (along sition ofthe avifauna as the vegetation recov- only67% ofthe transect), numbers fell to 7on ers to its pre-fire state (Woinarski and Recher the complete transect post-fire (Green and Sa- 1997). The overall post-fire response of birds necki 2006). Later, in May (when individuals in forests in eastern Victoria was an immedi- were counted), there were four species on the ate reduction in abundance followed by recov- transect (which is within the range previously eryovertheensuingthreeyears,a pattern that recorded on the transects) but there were 77% is general across temperate eucalyptus forests fewer individuals than recorded by Osborne (Loyn 1997). Lindenmayer et al (2008) found and Green (1992) for the same month (Green across 10coastalvegetationtypeslittleeffecton andSanecki 2006).This ishigherthanthe40% birdspeciesrichnesspersistingbeyondthefirst reductionrecordedbyLoyn(1997)inafirethat year post-fire. In temperate eucalyptus wood- was also oflarge extent (228000 ha cf700000 landandforestthestructuralcomplexityrecov- ha). This is the general response of birds to ered rapidly because ofepicormic resprouting fire, with a decline owing to reduction offood from the trunk and major limbs oftrees, and availabilityand a loss ofcover (Woinarski and this may be key to the recovery ofbird num- Recher 1997). Shrub coverwasessentiallyzero bers (Lindenmayer etal. 2008). In theabsence and,whereSnowgumshad notlosttheirleaves, ofepicormic resprouting, and the dependence these soon yellowed and died due to the effect on slower regrowth oftreestems from aligno- offireringbarking thetrees(Fig4;pers. obs.). tuber,thegeneral responseofbirdsinsubalpine Althoughsome birds maybe attracted tofire woodland is in marked contrast to other areas (Woinarski and Recher 1997) there was little ineasternAustralia,particularlywiththelong- observedinfluxofbirdstothe2003 firesathigh erduration ofrecovery. altitudes, although ina number offires White- Immediatelyafter the firein burnt woodland throated Treecreepers Connotates leucophaea (February 2003), the only bird species present were commonly heard even while fire crews were those thatoverwinterand there was a re- weremoppingup (pers. obs.). duction in numberd of individuals to winter The longer term response ofbirds to fires is levels (Green and Sanecki 2006). Keyto there- the progressive return to the original compo- duction in numberofbirdspeciesand individ- Year Fig.6.Numberofbirdspeciesobservedatthetimeofmaximalspeciesnumbersontheunburntwesternaque- duct(squares)andatthesametimeontheburnttransectonDisappointmentSpur/aqueduct(circles). 246 TheVictorianNaturalist Contributions uals following the fire was a reduction in for- Whilst there was a steady regrowth ofshrubs agingniches. The foraging substratesthatwere (Fig. 4) some ofthese took a long time to re- absent, and that did not recover quickly, were cover, and food sources such as flowers from canopy, lower branches and leaves, bark and the obligate seed regenerator G. victoriae were shrubs. Theopennatureofthegroundbeneath notavailable until 2008. This slowed the return the woodland attracted the Flame Robin that of honeyeaters. In eastern Victoria, honeyeat- appeared onthetransect immediately afterthe ers almost disappeared after fire because of fire (Greenand Sanecki 2006) andoccurred in loss ofblossom and leaf-suckinginsects but, in springthroughout thestudy(Table 1).Thenext contrast to the present study, their numbersin- group to recoverwas notso much guild-based creased rapidlyinthefirstyearafterfire,andre- as residency-based, with the winter resident coveredto60%oftheirpre-firenumberswithin Little Raven Corvus melloriy Pied Currawong threeyears(Loyn 1997).Theabsenceofsomeof Strepera graculina, White-browed Scrubwren thesebirdswould also leadto followon effects, Sericornisfrontalisand Brown ThornbillAcan- e.g. therewould benocuckoos iftherewereno thizapusillaall returningwithin the first three breedingbirds,andnobreedingiftherewere no years, withthelattertwobeingmostnoticeable suitableshrubs/undergrowthavailable. on thetransect. Bird diversitywould beexpected tobegreater Whilst the White-throated Treecreeper ap- in vertically complex vegetation (MacArthur peared immediatelyafter thefireand the Olive and MacArthur 1961; Recher 1969) but, after Whistler appeared in the same month, these an intensive wildfire, recovery of complexity two species were thereafter absent in the early will taketime iftreestemsarekilled. Trees took stages ofvegetation recovery, the former ow- timetore-establishanditwasnotuntiltwoyears ingto thelackoffissuredbark (notpresent on post-fire that Snowgum seedlings and lignotu- regenerating stems) and the latter due to the ber regeneration from saplings that had lost all lack of thick shrubs. The Grey Shrike-thrush stems in the fire w^ere recorded (Pickering and Colluricincla harmonica classified by Loyn Barry 2005).Theregrowth ofwoodyvegetation , (1997)asacanopyinsectivore,butwhichcom- (through epicormicshoots) anddenseregrowth monlyfeedsonthegroundandalsostripsbark ofshrubsinsouth-easternAustraliacanresultin from Snowgum and then investigates it on the populationdensitieshigherthanpre-fire(Woin- snow surface (Green and Osborne 2012), was arskiand Recher1997),withthehighestspecies slowertoreturnthanotherwinterresidentsbe- diversityoccurring5to6yearspost-fire(Catling cause ofthe lack ofthese two food sources. By and Newsome 1981). This is not the case in theendofthetenyears,thecanopystillhadnot Snowgumwoodland; therecoveryto date, after recovered, and sightings ofthe canopy insecti- one decade, has been in species numbers with vores Spotted Pardalote Pardalolus punctatus afewindividuals ofspecies such ashoneyeaters , Striated PardalotePardalotusstriatusand Grey beingableto find food, butnotin the numbers Fantail Rhipidura albiscapa (which forages found elsewhere in unburnt wroodland. Den- through allstrata includingtallshrubs, making sityofindividualbirdsinburntwoodlandisstill aerial captures) and large seed-eaters, Gang- less than a third of that in unburnt w’oodland. gang Cockatoo Callocephalonfimbriaturn and The next phaseofrecovery will bethe recovery Crimson RosellaPlatycercuselegans were rare. in numbers ofindividual birds as more forag- > This is in contrast to eastern Victoria where ing niches become available (particularly the canopy insectivores followed the general pat- canopy) and the productivity ofcurrent forag- tern ofimmediate post-fire decline with rapid ingniches(suchasflowers)increases. Hencethe recovery and an apparent increase in numbers avifaunaofsubalpinewoodlandappearstohave as the birds fed in new epicormic regrowth, alongrecoverytimeaheadofit. whichattractsinsects(Loyn 1997). Acknowledgments Osborne and Green (1992) found that the proportion ofinflorescences with open flowers eIdthoannkthWeilmlanOussbcroirpnte.andBobGreenwhocomment- was asignificant factorinfluencing thenumber ofbird species present in subalpine woodland. Vol 130 (6) 2013 247 Contributions References KornerC (2012) Alpine Treelines - FunctionalEcologyof Banks JCG (1989)Ahistoryofforestfire intheAustralian the Global High Elevation Tree Limits. (Springer: Basel, A2l6p5s-.28I0n.ThEedscRiBentGiofiocds.ig(nAiufsictarnacleiaonftAhlepAsusLtiraailsoinanCAolmpsm,iptp-. LiSnwdietnzemralyaenrd)DB,WoodJT,CunninghamRB,MacGregorC, Butrere:owCsanGbeKrr(a2)002)EpicormtcstrandstructureinAngopho- CR,raannedMG,illMiAchMae(l20D0,8M)oTnetsatginuge-hDyrpoatkheesR,esBarsoswonciDa,teMduwnittzh ra, Eucalyptus and Lophostemon (Myrtaceae) - implica- bird responses to wildfire. Ecological Applications, 18, t1i1o1n-s1f3o1r.lireresistanceandrecovery.NewPhytologist153, Lo1y9n67R-H198(31.997) Effectsofan Extensive Wildfire on Birds CattIrnlaiFlniigarnePavCnerdatnetdbhreaNAteueswtfsraoaulmniaeantAoBHifoitr(ea1:,9a8p1np.)e2Rv7oe3ls-up3to1ino0sn.easErdyosfapAtphMreoAaGuiclshl-., Mai2cn21AF-ra2tr3h4uE.rasRtHernanVdicMtoarciAa.rtPhaucrifiJc\VCo(n1s9e6r1v)aOtinonbiBridolsopgeycie3s, CRaHnbGerrorvae)sand1RNoble.(AustralianAcademyofScience: OsdbioverrnsietyW.SEcaonlodgyGr4e2e,n59K4-5(91989.2)Seasonalchangesincom- CDooRtsdehtsgoioinuonsnAanBIoKdf,N(y1Dee9aew5r4sSS)aooiuAfitsehSnTt,vWuaidMlryeyoseno.rmfse(tnGhCtoeavAlEecraconnhsmdyaesntnSgethemasParrnpiodnftAeth)rhu:e(m1SMa9yo9ndn4na)eirymAo)- PivpSceokngseoierttwiiaynotgniM,vCoeauMbnruteaancnidodnvasen.rBcyaeErroamyfnudKE9uf2co(.ra2al90gy30ip5-nt)1gu0Ss5bi.eznhei/apavhgioeopuhdiritsoatfrib(bisurntdoisowingnuatmnh,de pactinthealpine/oneatMtKosciusko,NewSouthWales. Myrtaceae)oneyearafterlireinKosciuszkoNationalPark. AustralianGeographer25,77-87. AustralianJournalofBotany53,517-527. Good RB (1992) Kosciusko Heritage. (National Parks and RecherHF(1969)Birdspeciesdiversityandhabitatdiversity WildlifeServiceofNSW:Hurstville) inAustraliaandNorth America.AmericanNaturalist103, Green K (2006) The effect of variation in snowpack on 75-121. timingofbird migration in the Snowy Mountains. Emu Wimbush DJand ForresterRI(1988)Effectsofrabbitgraz- 106,187-192. ingandfireonasubalpineenvironment.11Treevegetation. GrtCehheeantAsKuwsotaronacd!l)iOasnbSonrnoewWCoSun(t2r0y12,)(NFieewldHGoulildaendtoPWuiblldilsihfeerso:f WoAAiunsarterrvsaikleiiwaJnoCJfZotuahrennadelfRfoeefcctBhsoetroafnHfyFir3e6(,1o9n2987t7)h-e2I9mA8up.satcrtalainadnraevsipfoanusnae.: Green Kand Sanecki G (2006) Immediate andshort term PacificConservationBiology3,183-205. responsesofbirdandmammalassemblagestoasubalpine wildfireintheSnowyMountains, Australia.AustralEcol- ogy31,673-681. Received28February2013;accepted25July2013 The ‘holygrail5 ofVictorian insects - found at last and now in print! AHandbookofTheDestructiveInsectsofVictoria Part VI Charles French Thelongdiscussedbutnotseenmanuscript forCharles French’sA HandbookofTheDestructiveInsects ofVicto- ria Part VI was found while clearing out the Knoxfield location ofthe Department ofPrimary Industries. The handwrittentextandoriginalplateswereeditedbyAlan Yen, GordonBerg,TimNewand PeterMenkhorst. Part VIwasprintedinalimitedrunof150copiesbytheDe- partment of Primary Industries. It is hard bound and printed in the same size and format as Parts 1-V, with fullcolourplates. The sole outlet for this book is the Field Naturalists Club ofVictoria. Forfurther information, email: book- [email protected]. Cost$90 PJ*kCXXXXJU. 248 TheVictorianNaturalist