The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (B&N) PDF

Preview The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I (B&N)

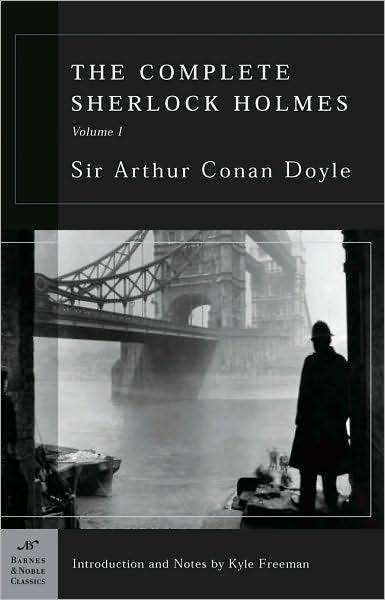

The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is part of the Barnes & Noble Classics series, which offers quality editions at affordable prices to the student and the general reader, including new scholarship, thoughtful design, and pages of carefully crafted extras. Here are some of the remarkable features of Barnes & Noble Classics:

- All editions are beautifully designed and are printed to superior specifications; some include illustrations of historical interest. Barnes & Noble Classics pulls together a constellation of influences—biographical, historical, and literary—to enrich each reader's understanding of these enduring works.

__

The Complete Sherlock Holmes comprises four novels and fifty-six short stories revolving around the world’s most popular and influential fictional detective—the eccentric, arrogant, and ingenious Sherlock Holmes. He and his trusted friend, Dr. Watson, step from Holmes’s comfortable quarters at 221b Baker Street into the swirling fog of Victorian London to exercise that unique combination of detailed observation, vast knowledge, and brilliant deduction. Inevitably, Holmes rescues the innocent, confounds the guilty, and solves the most perplexing puzzles known to literature.

Volume I of The Complete Sherlock Holmes starts with Holmes’s first appearance, A Study in Scarlet, a chilling murder novel complete with bloodstained walls and cryptic clues, followed by the baffling The Sign of Four, which introduces Holmes’s cocaine problem and Watson’s future wife. The story collections The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes feature such renowned tales as “A Scandal in Bohemia,” “The Red-Headed League,” and “The Musgrave Ritual.”

Tired of writing stories about Holmes, his creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, killed him off at the end of “The Final Problem,” the last tale in The Memoirs. But the public outcry was so great that eight years later he published the masterful The Hound of the Baskervilles, which supposedly takes place before Holmes’s death.

The separate Volume II of The Complete Sherlock Holmes collects the remaining accounts of Holmes’s exploits, including “The Adventure of the Empty House,” which reveals the elaborate circumstances behind Holmes’s literary resurrection.

Kyle Freeman, a Sherlock Holmes enthusiast for many years, earned two graduate degrees in English literature from Columbia University, where his major was twentieth-century British literature.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.From Kyle Freeman’s Introduction to The Complete Sherlock Holmes, Volume I

__

Arthur Conan Doyle began writing A Study in Scarlet in 1886 while waiting for patients in his newly furnished doctor’s office in Southsea, Portsmouth. He sent it to what seemed like every publisher in England before it was finally accepted by a small firm called Ward, Lock & Co. He was paid a one-time sum of £25, relinquishing all other rights to the publisher. The company thought it would be most effective in one of its big holiday issues, Beeton’s Christmas Annual, so Conan Doyle had to wait nearly a year before seeing it in print in December 1887. Thus after this long and uncertain gestation the world finally saw the birth of the resplendent career of the character who would become the greatest literary detective, Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle got the idea for a detective story from the acknowledged creators of the genre. Edgar Allan Poe had written three short stories featuring Parisian sleuth C. Auguste Dupin: “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” and “The Purloined Letter.” Conan Doyle lifted so much detail from Poe that he seemed a plagiarist to some. He took several key components from Dupin. Holmes, like Dupin, is a prodigious pipe smoker. He also places ads in the newspaper to lure the perpetrator of the crime to his apartment. He goes to the scene of the crime to find clues the police had overlooked. Yet another component borrowed from Dupin was his trick of breaking in on his companion’s thought process by guessing the links in his train of thought. Ironically, Holmes complains in this first story that this habit of Dupin annoys him, but apparently not as much as he claims, as he adopts it himself in two later stories. Most important, like Poe, Conan Doyle decided to give his detective a companion to narrate the case.

Such a narrator provides several advantages. He can frame the story more dramatically than the detective could because the companion is in the dark about the outcome. He therefore can sustain suspense and share his surprise with us when the mystery is solved. The narrator also has the freedom to glorify his friend, something the detective as narrator couldn’t do for himself without suffering the inevitable backlash from readers who don’t usually take kindly to braggarts.

Conan Doyle also borrowed from the work of Émile Gaboriau, a Frenchman who wrote the first police novels. His Inspector Lecoq uses scientific methods to build a solid case against the criminal piece by piece. Holmes’s scientific method owes the most to this source. Gaboriau also divides his novels into two equal parts, with flashbacks to prior action, a device Conan Doyle copied in the first two Holmes novels. Conan Doyle based Holmes’s deductive process—lightning quick and seemingly intuitive, though informed by careful observation of detail and mountains of precise knowledge—on Conan Doyle’s teacher at the medical school at Edinburgh, Dr. Joseph Bell.

Once embarked on the process of stirring all these ingredients together, Conan Doyle had to choose a name for his detective. The first he chose was J. Sherrinford Holmes, then Sherrington Hope, and finally the one we know today. We don’t know where he got the name Sherlock, but we can be sure that the last name was a tribute to Oliver Wendell Holmes, the American physician and author, father of the great U.S. Supreme Court justice of the same name. Conan Doyle had read and greatly admired his work, saying of him, “Never have I so known and loved a man whom I had never seen.” On his first trip to America Conan Doyle made a reverential visit to the author’s grave.

__

A Study in Scarlet introduces the formula that almost all the other Holmes stories will follow. Someone seeks out the detective at his Baker Street rooms to solve an unusual mystery. Holmes and Watson then set out to explore the scene of the mystery. The police are often involved, but of course they never have a clue. After an adventure or two that builds suspense, Holmes solves the case in the most dramatic way. The two investigators end up back at Baker Street, where Holmes explains any point in his chain of reasoning that might have escaped Watson’s understanding, and all’s once again right with the world. Doyle varies this formula in minor ways in a few of the stories in this first volume, but not often. (He will cleverly foil our expectations of this pattern in later stories.) This plot repetition, which might seem a weakness, turns out to be a strength. It contributes to that sense of solidness we get from this world in which logic triumphs over superstition, and where justice in one form or another is meted out to violators of the social order. The sense of order that runs through this world is one of the great satisfactions of these stories. No matter how bizarre the circumstances, Holmes will tender a rational explanation for everything. Criminals are caught not because they make a fatal error, but because all human actions, good and bad, leave traces behind. If you pay close enough attention to the causative chain of events in everyday life, and you’ve trained yourself to think logically, you’ll be able to follow that chain when someone has committed a crime.