The Beretta M9 Pistol PDF

Preview The Beretta M9 Pistol

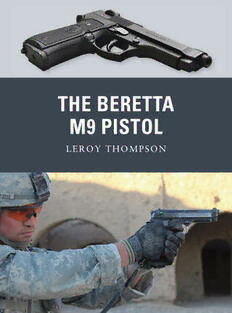

THE BERETTA M9 PISTOL LEROY THOMPSON © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE BERETTA M9 PISTOL LEROY THOMPSON Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 7 The first military Berettas USE 25 Modern warfare’s 9mm IMPACT 62 In service around the world CONCLUSION 76 GLOSSARY 78 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 79 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Innovation in military weapons and equipment is generally viewed as a positive factor that allows the soldier a higher probability of fighting, surviving, and winning. Ironically, however, it is often easier to adopt new multimillion-dollar weapons systems than it is to replace personal weapons or equipment. A simple example might be the US P-38 can opener, which was issued to GIs from World War II through the 1980s. This simple device worked and was small enough that a GI could wear it on the chain with his dog tags. Had the US Army tried to replace the P-38 can opener with something larger and more complex, it would have met stolid resistance from the troops. As it transpired, the P-38 met its demise not through innovation but through obsolescence. When US troops started receiving MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) in the 1980s, the small can opener was no longer necessary. For the typical soldier, no piece of equipment is more personal than the individual weapon – for infantrymen the rifle and for others, such as crew-served weapons operators, Military Police, or technical personnel, the pistol. During the early days of the Vietnam War when the .30-caliber rifle was replaced by the 5.56mm M16, long-serving troops complained they were being sent to war with a “.22-caliber mouse gun.” Veterans of World War I, World War II, and Korea who had used the .30-06 Springfield M1903 or Garand rifles decried the end of “the US Army as we know it” and the sending of their sons and grandsons into combat to be killed by Communist guerrillas armed with a .30-caliber rifle in the form of the SKS or AK-47. Obviously, this reluctance was overcome as the M16 has gone on to become the longest-serving infantry rifle in US history, though there are still calls to return to a larger caliber and many troops in Afghanistan and Iraq are now carrying .30-caliber rifles. For much of the last century the pistol has held a contradictory 4 position in many armies. REMFs (Rear Echelon Mother F***ers) have © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com generally attempted to lessen the number of pistols issued because of the weapon’s “ineffectiveness.” Combat troops, on the other hand, have tried to acquire a pistol in any way possible. It’s not that they consider the pistol the optimum weapon, but that the pistol has great propinquity. It can be with the soldier while he goes to the latrine, eats a meal, or relaxes. It can be kept near to hand while asleep, sometimes with a wrist thong. Should the rifle malfunction, the pistol allows the soldier to defend himself. The pistol may also be operated effectively with one hand should the soldier be injured. Nevertheless, in many armies the pistol has been considered expendable for the large majority of troops. One often- heralded replacement is the PDW (Personal Defense Weapon) of which the FN P90 is the current fair-haired example. Traditionally, in the USA there has been more of a culture of the handgun than in most countries. That has been reflected in the US armed A US Marine trains with his M9 forces, especially during World War I when a handgun was considered a on the range in Iraq. (USMC) © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com boon in trench warfare and today in Iraq and Afghanistan where the constant threat of attacks by insurgents, even in “rear areas,” makes a companion weapon a virtual necessity. During World War II, the US Army tried to replace the handgun with the M1 Carbine. Many troops that would have previously been issued a handgun found the M1 Carbine a handy replacement, but many supplemented it with a handgun. From 1873 until 1985, apart from a decade or so at the beginning of the 20th century, the US military’shandgun was normally in .45 caliber. In many otherarmies, the handgun was virtuallya symbol of officer status, rather than an effective fighting weapon. Often, it was in the anemic .32 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) chambering. Even widely used 9×19mm handguns such as the Luger, P-38, or Browning Hi-Power were marginally effective as manstoppers with their 115–124-grain (7.45g–8.04g) full-metal-jacketed bullets. From 1911 until the 1980s the principal US handgun was the Colt 1911/1911A1 pistol. Some GIs hated the 1911, finding the recoil heavy and the pistol inaccurate – the two were related. But the 230-grain (14.9g) .45 ACP round was a manstopper. Those shot with the .45 auto tended to go down and stay down. As a result, when the US armed forces decided to replace the 1911 pistol with a 9×19mm pistol, there was substantial resistance. There were, however, some telling arguments. Most of the 1911 pistols in the inventory were at the end of their useful service. The newest had been produced during World War II or in the first months after peace and had seen service in multiple wars. They were worn out. Another argument was that NATO allies used 9×19mm pistols: hence, the US should as well. Training soldiers who had never fired a handgun to fire the .45 auto effectively had always presented something of a problem, but it was felt that the lighter-recoiling 9mm round would allow soldiers to gain greater proficiency with the pistol. A greater influx of female soldiers with smaller hands and, probably, more sensitivity to recoil proved another impetus to selecting a new service pistol. Still another argument in favor of a double-action, high- capacity 9mm pistol was that it would give the individual soldier more available ammunition and could be carried safely with a loaded chamber yet ready for a first double-action shot. Multiple trials led to the selection of the 9×19mm-caliber Beretta M9 pistol as the US service pistol. Controversy surrounded the trials, with allegations that the outcome was predetermined through nefarious means and that the Beretta was chosen in return for some military concessions from Italy. In any case, the M9 was adopted in 1985 and entered general service in 1990. Since then, many hundreds of thousands of M9s have been acquired and are in use with all branches of the US armed forces. The debate over .45 versus 9mm has not ended. Many US special operations troops have returned to the use of the .45 automatic pistol. A few years ago, too, there were trials of a sort – certainly, bid specifications were issued – for a new Joint Combat Pistol in .45 ACP caliber. Even so, as the Department of Defense recently gave Beretta an order for hundreds of thousands of M9s, the M9 remains the standard US military pistol and 6 appears likely to continue in service for some time. © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com DEVELOPMENT The first military Berettas BERETTA – THE BACKGROUND Established in 1523, Beretta is the world’s oldest corporation, and has been owned by the same family throughout its history. Prior to World War I, Beretta primarily produced shotguns. Beretta’s first military pistol was produced in 1915 for the Italian Army to supplement the M1910 Glisenti and M1912 Brixia pistols then in use. Both pistols were chambered for the 9mm Glisenti cartridge, which was 0.02in (0.51mm) shorter than the 9×19mm Parabellum cartridge and fired a 124-grain (8.04g) jacketed bullet at 1,050fps (320m/s). Although the 9mm Glisenti and 9mm Parabellum cartridges were theoretically interchangeable, because pistols chambered for the 9mm Glisenti round were blowback designs it was generally considered unsafe to fire the Parabellum round in them. The Beretta M1915 was also a blowback design chambered for the 9mm Glisenti round of which it held seven cartridges. Reportedly, 15,300 M1915s were produced for the Italian Army during World War I, and a few hundred commercial versions were sold as well. Total production is usually given as about 15,670. At least some examples of the M1915 probably saw service in World War II, as the 9mm Glisenti round remained in service. As Beretta’s first military pistol and first pistol chambered for a 9mm round, the M1915 is an important landmark towards the development of the M9. After deliveries of the M1915 had begun, Beretta was given an order for a less expensive, smaller pistol chambered for the 7.65mmBrowning (.32 ACP) cartridge. The resulting pistol, designated the M1915/17, was lighter, smaller, and simpler in design, and it held one more round. Many features of the M1915, which had been designed to handle the more powerful 9mm Glisenti cartridge, were eliminated due to the chambering of the lighter 7 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 7.65mm round. Serial numbers of the M1915/17 started at the end of the range for the M1915. After an initial military order for 10,000 of the M1915/17, production continued until at least 1921, with somewhere over 56,000 pistols being produced for military and commercial sales. Reportedly, a substantial number of the M1915/17 pistols stayed in the Beretta inventory until sold to Finland during the Winter War of 1939–40. Beretta was now in the automatic pistol business for good, though many of the pistols produced in the early post-World War I years were small 6.35mmBrowning (.25 ACP) pocket pistols for the civilian market. An updated version of the M1915/17, the M1922, was produced during the early 1920s, but of more interest for this book was the M1923 in 9mm Glisenti. As a result, the basic Beretta design was “up-sized” to take the larger and more powerful cartridge. An important innovation on this pistol was the use of an external hammer. Also, since the M1923 was still a blowback design, a recoil-absorbing buffer disk was incorporated. With the military market obviously in mind, the M1923 was designed to take a shoulder stock, though only 20–25 percent were actually cut to take a stock. Sales of the M1923 were not great. Sales to the Italian Army accounted for 3,007, while a number were also sold to Italian colonial forces. The Fascist militia purchased 250, of which 100 had shoulder stocks. Substantial numbers were sold to Bulgaria and the Argentine police as well. Production ran until around 1925, with approximately 10,400 pistols sold. Because of the incorporation of the external hammer and the 9mm Glisenti chambering, the M1923 is of interest for the future development of larger-caliber Beretta service pistols. Although Beretta had sold a number of pistols to the Italian armed forces, it was with the development of the M1934 and M1935 that the company obtained major military contracts. The M1934 was adopted first by the Italian police and later by the Italian Army in 9mm Corto (.380 ACP) caliber. Beretta’s first military automatic A blowback design with an external hammer, the M1934 used a seven-round pistol, the M1915 in 9mm Glisenti caliber. (Pete Cutelli) detachable box magazine with a distinctive “tongue” or “hook” at the bottom to offer a finger rest. Although the 9mm Corto chambering was somewhat weak for a military pistol, the M1934 was reliable and, with a length of about 6in (152.4mm) overall and a weight of 26oz (737g), compact and easily carried. Although 9mm Glisenti pistols remained in use during World War II as did some other older models, the M1934 went a long way towards allowing the Italian Army to standardize on one pistol. Captured M1934 pistols proved a popular souvenir with US GIs, who brought them back from World War II. Many had the hook at the bottom of 8 the magazine ground off so the GI © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com could tuck the pistol into a battledress pocket yet still draw it quickly. In addition to the Italian Army, the Romanian Army also purchased M1934s. Finland, which was a co-belligerentwith the Axis during World War II, also purchased at least some M1934s. The M1934 continued in production after World War II as a commercial police and self-defense pistol until 1991, with over one million examples being produced. Infamously, a Beretta M1934 pistol was used to assassinate Mahatma Gandhi. The Italian Navy had acquired a few thousand of the Beretta M1931 in 7.65mm Browning caliber, but it was the M1935 which was purchased in substantial quantity by the Italian Navy and Air Force. Basically an M1934 in 7.65mm The M1934, the Italian Army’s Browning chambering, the M1935 held eight rounds of the smaller pistol during World War II, was Beretta’s most successful military cartridge. As with the M1934, the M1935 remained in production after pistol prior to the Model 92/M9. the war and was sold in large numbers commercially around the world. (Pete Cutelli) In April 1943, the Germans took over the Beretta factory and, since they used 7.65mmBrowning caliber pistols for support troops, concentrated on producing the M1935. At least some M1934 pistols may have still been produced for the remnants of the Fascist Italian Army, but production during the last two years of the war was almost entirely of the M1935. It is interesting to note that at least some M1935s were sold to Japan. By the time production ceased in 1967, approximately 525,000 had been produced, 204,000 of them during World War II. As with the M1934, the M1935 was a very popular war trophy. In 1938 Beretta had tested a larger 9×19mm Parabellum pistol that resembled a scaled-up M1934. Romania was interested in this weapon, but with the beginning of World War II this pistol, which was designated the M1938, never went into production and only a small number of prototypes were ever produced. Beretta’s first locked-breech, 9×19mm pistol had to wait for development until the late 1940s. The M951, as this pistol became known, though it was also at times designated the M1951 or the M51, employed a short-recoil, locked-breech design with a falling locking block showing similarities to that used in the Walther P-38. One distinctive feature of the M951 that has been retained on later 9×19mm Beretta pistols, including the M9, is the open top slide. The M951’s hammer is exposed and the safety is a cross-bolt on the frame beneath the hammer. Magazine capacity is eight rounds with the magazines incorporating a curved finger rest, though not one as dramatic as on the M1934. A hold-open device locks the slide open after the last round has been fired. Sights are a fairly rudimentary front blade and rear notch. In an attempt to reduce weight, a test run of around 100 M951 pistols with aluminum alloy frames was made. Weight was only 25.4oz (720g), but Beretta engineers decided to use a steel frame in the production pistol, which 9 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com raised weight to 31.4oz (890g). Early examples also had a butt magazine release that was switched to the lower portion of the grip. The Italian Army did not choose to adopt the M951 and retained the M1934; however, the Italian Navy and the Carabinieri did adopt it. Until relatively recently, Italian law forbade civilian ownership of pistols in military calibers such as 9×19mm Parabellum. As a result, for the Italian civilian market, Beretta offered the M952, which was exactly the same as the M951 but chambered for the 7.65 Parabellum (.30 Luger) cartridge, which is basically a necked-down 9×19mm – consequently, only the barrel had to be changed to convert an M951 to an M952. Collectors in the USA and elsewhere have often found the Italian 7.65mmParabellum versions of pistols, normally in 9×19mm caliber, interesting curiosities for their collections. The Egyptian Helwan pistol, Among other countries that adopted the M951 were Egypt and Iraq, which was based on Beretta’s which produced it on license as the “Helwan” and the “Tariq” first pistol in 9×19mm caliber, the respectively. Israel also purchased and used a substantial number of M951 M951. The Helwan remained the pistols. For civilian sales in the USA, the pistol was known as the M951 standard Egyptian military pistol for many years. (Tom Knox) “Brigadier.” Production of the M951 by Beretta continued until 1980, with somewhere over 100,000 being produced, though it had been superseded in Italian military service. An interesting variant of the M951 was the M951R, R standing for “Raffica” (burst). This pistol was select-fire and had a folding vertical foregrip and a ten-round extension magazine. Only a limited number of M951R pistols were produced, though the later M93R select-fire model proved more popular. THE “WONDER NINES” ENTER THE SCENE The M951’s demise was hastened in the early 1970s by the advent of the The Iraqi Tariq pistol, which was “Wonder Nines.” This term is often applied to the first generation of still in use during the two recent combat pistols that combined the first-round, double-action trigger pull of wars in Iraq, was based on the Beretta M951. (Author’s photo) the Walther P-38 with the double-column, high-capacity magazine of the Browning Hi-Power. In the postwar years, there had been substantial interest in 9mm double-action pistols, the Smith & Wesson Model 39 of 1954 having been developed with possible US military adoption in mind. Actually, the US Air Force acquired a limited number of Smith & Wesson Model 39s for issuance to general officers. In France, large-capacity magazines had been explored with the MAB P- 15. The West German VP70, which took its designation from 1970, the year of its design, offered many features that © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com