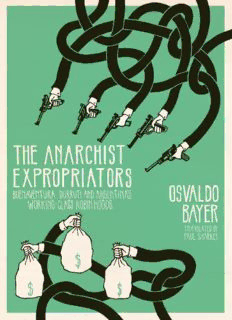

The Anarchist Expropriators: Buenaventura Durruti and Argentina’s Working-Class Robin Hoods PDF

Preview The Anarchist Expropriators: Buenaventura Durruti and Argentina’s Working-Class Robin Hoods

THE ANARCHIST EXPROPRIATORS Buenaventura Durruti and Argentina’s Working-Class Robin Hoods Osvaldo Bayer Introduction It’s a chastening thought that Osvaldo Bayer wrote this book nearly forty years ago and his work still challenges us, as anarchists, with ideas, arguments, and problems that are still as relevant today as they were in 1975 or, indeed, as when the actions of this narrative were originally carried out. Much of Bayer’s work belongs to the first wave of modern anarchist historiography that was, and still is, concerned with excavating anarchism’s stories; research that began to challenge our ideas as to what anarchism is and had been. Some of those early pioneering works include those by James J. Martin (1953) and Voline (first English translations in 1954 and 1955) as well as the works of Antonio Tellez (1974 in English), Bill Fishman (1975), Hal Sears (1977), and Paul Avrich (1978).1 These authors, together with Bayer and others, made the 1970s an exciting time for anarchist research. The Anarchist Expropriators was first published in 1975 as Los Anarquistas Expropriados y otros ensyos and is here published in its first English translation. It appeared shortly after what we consider to be Bayer’s greatest work, the four volume La Patagonia Rebelde (1972–1975), soon to be published in one volume as Rebellion in Patagonia by AK Press. A later work, Simon Radowitzky and the People’s Justice (1991), was recently published by Elephant Editions. Bayer and some of the other writers mentioned here were lucky enough to know some of the relatives and comrades of those who feature in their work, and this knowledge informs their narratives with a richness and immediacy that later histories often lack. The Anarchist Expropriators is a companion piece to Bayer’s earlier work Severino Di Giovanni idealists de la violencia (1970), which was translated into English as Anarchism and Violence by Elephant Editions in 1985. The main protagonist of that work, Severino Di Giovanni, is glimpsed only occasionally in this volume, which in essence concentrates on other groups of anarchists carrying out acts of expropriation and revenge both alongside Di Giovanni and his comrades and after Di Giovanni’s execution on February 1, 1931. It presents us with additional information on the Argentinian anarchist expropriation movement that peaked during the twenties and thirties. Vicious infighting between anarchists, ruthless state opposition, bad luck, and its own ineptness destroyed this complex, challenging, and provocative movement, and Bayer attempts to show how that happened. Like Anarchism and Violence, the book is short on analysis but long on action. Events hurtle along at breathtaking speed and, by the final page, we are left breathless (and a little confused as to what has just happened!). It is best not to read this book as a portrayal of the romantic outsiders who cannot fit into society and take a principled stand against all the everyday hypocrisies they see in anarchists and the rest of the world—the Stirnerite individualists going out guns blazing, proudly proclaiming their identity in a world that constantly attempts to suffocate them. Undoubtedly there are traces of that, but the people here are a little different from Di Giovanni and others who featured in Bayer’s earlier work. You won’t find in these pages the heightened language, the passionate hyperbole, the tragic hero set against the world. Men such as Miguel Arcangel Roscigna and Juan Antonio Moran seem much more hardheaded and pragmatic. In different circumstances, they could have been the 1936 version of Durruti who survived his own expropriation career and, during the period covered by this volume, was no different from these men. Indeed Durruti thought so highly of Roscigna and his activities that he wanted him to come to Spain and help with the anarchist struggle there. Argentinian anarchism in the twenties and thirties was a product of brutal state repression against a movement that, in the early part of the twentieth century, was a force to be reckoned with.2 This repression, exemplified by the events of 1st May 1909, the Social Defense Law of 1910, and the Tragic Week of 1919, together with a constant, brutal day-to-day treatment at the hands of the police and other agencies, reflected the concern anarchism engendered in the authorities. Reacting to these and other factors, such as the popularity of syndicalism among the working class, some anarchists began to analyze and reflect on what they believed and where they thought these beliefs should take the movement. Spurred on by the events of the Russian revolution, writers such as Lopez Arango and Abad de Santillan, for instance, were teasing out the relationship between syndicalism and anarchism in the labor movement, discussing the nature of trade unions, and the intricacies of class as the “lodestar” of anarchism as they attempted to rebuild a movement that would bring about the world they desired. The primary vehicle for this discussion was La Protesta, the paper they edited. All this is well and good, but there were still profound differences in the movement and, as is so often the case, this slice of anarchist history reverberates with internecine quarrels—quarrels that became bitter and bloody but, in themselves, are reminiscent of similar quarrels in other countries and at other themselves, are reminiscent of similar quarrels in other countries and at other times. In essence, they revolved around those constant and exhausting questions of what anarchism is and the best way to practice it and bring about anarchy. Bayer is careful to try to delineate the complexities of these differences and provides us with a useful guide to understanding them. But there is still a little more that we may need to consider. Personality clashes and questions of ownership of resources had a deleterious effect on theory and practice. The execution of one of La Protesta’s editors, Lopez Arango, probably by Di Giovanni, in October 1929 is chilling. This though was not the first time that violence had occurred within Argentinian anarchism. We should remember that, in August 1924, gunmen from La Protesta raided the anarchist paper Pampa Libre leaving one dead and three wounded. These were not simply intellectual and practical differences between comrades, but ones that were visceral, deeply felt, and with deadly consequences. Such tensions brought about some kind of fractured dialectic between the realities of the world outside the movement and the antagonisms within it. The results were not edifying. Understanding the development of these tensions is not easy from this distance. One senses that much of the antagonism on the part of those around La Antorcha (presented in this volume as essentially La Protesta’s most constant critic) who had broken away from La Protesta in 1921, consisted of a number of factors. A major concern was the printing press and resources that La Protesta owned: who gave the present editors the right to own them and why weren’t these resources shared across the movement? Secondly, and just as importantly, was the fact that La Protesta saw itself as THE paper of the Argentinian anarchist movement (with the backing of the FORA) while La Antorcha saw itself as ONE of the papers of a much more diverse anarchist movement than the one with which those around La Protesta identified. The editors of La Antorcha certainly did not offer whole-hearted support to the expropriators, but it did support expropriator anarchists who were imprisoned (unlike La Protesta who saw them as “anarcho-bandits”). It also condemned La Protesta’s habit of naming or slandering those who had committed expropriations (La Protesta, for instance, described Di Giovanni as a “fascist agent”), calling the editors police informers. Hence the question of violence may not have been quite as central as Bayer suggests in driving the antagonism between the two papers. All this, remember, occurred between groups of people, many of whom had worked together in previous years, and indeed would in future ones. A feature of the Argentinian movement was its internationalism. Italian, German, Spanish, and Russian anarchists regularly traveled in and out of the country, providing the movement with both a richness of ideas and strategies, as well as all the practical realities that internationalism actually meant—not so much a theory, more a way of life. The French anarchist Gaston Leval was associated with La Antorcha, while Abad de Santillan, one of the editors of La Protesta, was in Berlin between 1922 and 1926 working with the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) as the Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation (FORA) delegate, and this is reflected in the pages of the various newspapers. La Protesta regularly sent assistance back to Italian anarchists both before and after the rise of Italian fascism, while many articles from the strong Italian anarchist community in Argentina were aimed at those anarchists trapped in Italy or in exile, as well as attacking Italian fascists in Argentina. Meanwhile, La Antorcha published writings on the situation for anarchists in Russia as well as in Italy and other countries. It should come as no surprise, then, that the struggle against fascism resonated within the Argentinian anarchist movement. The struggle against the death sentence placed on Sacco and Vanzetti was equally important and influential. Di Giovanni and others were in regular contact with the American, Italian-language paper L’Adunata dei Refrattari throughout the campaign and, after the executions, Sacco’s companion wrote to Di Giovanni thanking him and his comrades for their efforts on behalf of the two men; efforts that had included bombings as well as other more sedate propaganda activities. This internationalism took an interesting turn in early August 1925 with the arrival of members of the Spanish “Los Solidarios” group, who were on the run from Europe and fresh from robbing a bank in Santiago, Chile. By October 1925 they had commenced activities in Buenos Aires and, by January 1926, had help and support from Argentinian comrades there. The Los Solidarios members (Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover) were robbing banks, metro stations, and tram depots to raise funds to support revolutionary activity in Spain—and quite probably in Argentina too. During their time in the country, they became close to Roscigna and others who would be active in the fight to prevent the deportation of the three Spaniards from France to Argentina (they had left the country in spring 1926), where they were wanted for killing a policeman and a bank employee during the course of their robberies. It was a fight that La Protesta described as “not qualifying for the description of anarchist.” It was a statement that only added to the tension between the various anarchist tendencies. Roscigna belonged to part of the anarchist movement that insisted on maintaining what they felt was an ideological purity; there could be no joint front with communists against fascism or in support of Sacco and Vanzetti, for example. In Russia, these communists had been responsible for the murder, execution, and imprisonment of countless anarchists. To work with them in any way would betray the memory of these dead, and would dilute anarchism into some type of pragmatic convenience. How could people know what anarchism was unless it remained pure? An anarchist movement could not be built on joint and popular fronts. Rather Roscigna and others favored a sort of permanent confrontationalism, a constant war against capitalism and the state where anarchism would make no compromise. In 1924, the FORA had expelled those around La Antorcha and other anarchist papers from the “Comite Pro Presos y Deportados” (Prisoners and Deported Solidarity Group), and in response these papers had called for direct aid to anarchist prisoners, their families, and the families of those deported. For Roscigna and his comrades, the aim was not just getting funds to anarchist prisoners but to get them out of prison—and that would take time and money. To that end, he also became fascinated by the possibilities counterfeiting offered. In a sense his move to expropriation was a logical one, re-enforced by those from Spain who were engaged in the same strategy, who came from a similar social background as himself and possessed the moral purity he felt essential in order to describe oneself as anarchist. Moran, the other major protagonist of Bayer’s work, showed a similar pragmatism. Twice General Secretary of the powerful Maritime Workers Federation, Moran fought a constant running battle against scab labor and intimidation. It was a battle he felt could not be won by conventional means, and he was part of the group who decided to execute Major Rosasco, the man spearheading attacks on anarchists, labor radicals, and others. The statement of those who carried out the execution ended with the words “these proletarian fighters have shown, by executing Rosasco, how we may be rid of the dictatorship, root and branch.” Like the Spanish action groups, Moran shared the belief that, sometimes, extreme measures were the only defense available to unions and organizations. One had to fight fire with fire or be destroyed. Of course it is never that simple, never that straightforward. It’s easy for us to create patterns that were not there or lose sight of the nuances that have become hidden over the years. We can’t be certain why people do what they do or how events around them shaped their actions. We can say, though, to see the necessity of using arms to obtain funds does not necessarily mean that those who arrived at this position were any good at it in practice. Los Solidarios gained hardly any money from some of their efforts, while the Spanish anarchist group around Pere Boadas—a member of “The Nameless Ones” and not Los Solidarios as Bayer suggests—were murderously inept in their raid on the Messina Bureau de Change at the Plaza de la Independence on the afternoon of October 25th, 1928. Their arrest led to other raids being undertaken to fund their escape (which succeeded) and, eventually, their actions would lead to more arrests. As time went on, more of the groups were arrested, which resulted in more energy spent on working out how to free the imprisoned comrades. The groups began to live in a world of their own—always a danger in work of this sort, and especially so as the popular support base erodes. As part of his everyday work, Moran may have been able to chat with people who weren’t taking part in actions and, by doing so, he was able to temper his actions with realism. It became harder for others who, perhaps, grew more contemptuous of those who did not share their commitment and found it hard to know who to trust. The movement, if that is what it was, became more and more concerned with revenge on individual policemen as their comrades were killed and imprisoned. It became a small world of attack and counter attack with the protagonists known to each other, and everyone else relegated to onlookers. For the members of Los Solidarios there was always the organization in Spain; for the Argentinian anarchist expropriators there eventually was just themselves. Of course the tension with the various strands in the anarchist movement increased as the actions continued and state repression grew worse. None of the tendencies appeared to understand the position of the others. Indeed one senses that they were determined not to! For those around La Protesta the most important work that anarchists could do was to create a movement; to bring numbers of the working class and others to their cause; to hold meetings, talk to people, produce newspapers, and pamphlets that would build an educated, mass movement that could sweep the dirt of capitalism away. In their opinion, those in the action groups actively prevented this from happening. They put anarchism on the defensive, created a false impression of what anarchism was, and alienated everyone. If they did that, if they prevented the movement’s growth, they were, objectively, assets of the state. Looking at it now from the hindsight of ninety or so years it all becomes horribly poignant. There seems to be no common ground between the antagonists and, yet again, anarchist history gets bogged down in its own quarrels and vendettas. However we read and interpret Bayer’s work, it is a challenge to discover anything positive. Thoughtful attempts to define the ideas of anarchism and its possibilities as carried out by Santillan etc. on one hand, versus a frustration with theory and a logical move to expropriation, often characterized by exemplary bravery and courage, on the other. Yet there are matters that should concern us here. The ending is unbearable with the murder of Moran and the others. Just as painful, if not more so, is the escape attempt of the anarchist prisoners in Caseros. With no hope of outside help, essentially abandoned, they still made their attempt. Expropriators some of them may have been, but to abandon them? Surely no “correct” anarchist line is worth the abandonment of those who also profess anarchism. We may have the right answer (even if we haven’t the mass movement to celebrate the fact) but comradeship, in anarchism, has to sometimes cross the boundaries between those who agree with every word you say and those who question your methods and practices in the most profound way possible. As a comrade in La Antorcha wrote, “the expropriators were always better than those who repressed them” and it appears that some forgot this. Some of the survivors of this story appear again in Spain during the revolution. Some played important roles, others less so. All were fighting fascism and attempting to create the most profound revolution we have, so far, known. Abad de Santillan was working hand-in-hand with Spanish anarchists who had been members of action groups and, at times, expropriators. Circumstances change and, when you think you are winning, all is forgiven. As we said earlier, the qualities of a Roscigna, or a Moran, could have blossomed in Barcelona before the May Days of 1937 and if we want to admire a Durruti or Ascaso for how they made their lives (“mistakes” and all) in trying to help construct a new world, perhaps the anarchist expropriators are worthy of a similar respect. Let’s see where that takes us. —Kate Sharpley Library 1 James J. Martin, Men Against the State (De Kalb, IL: Adrian Allen, 1953); Voline, The Unknown Revolution (New York: Libertarian Bookclub, 1955); Antonio Tellez, Sabaté: Guerilla Extraordinary (London: Davis-Poynter, 1974); William J. Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals, 1875–1914 (London: Duckworth, 1975); Hal Sears, The Sex Radicals: Free Love in High Victorian America (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1977); Paul Avrich, An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978). 2 See for example, Juan Suriano, trans. by Chuck Morse, Paradoxes of Utopia: Anarchist Culture and Politics in Buenos Aires, 1890–1910 (Oakland: AK Press, 2010). Chronology of Events June 18, 1897. The first issue of La Protesta Humana is published. In 1903 it becomes La Protesta. March 25–26, 1901. FOA (Argentine Workers Federation) is formed with approximately ten thousand members. It is syndicalist in nature and rejects party political involvement. 1905. At its Fifth Congress, FOA becomes the FORA (Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation) with a commitment to anarchist communism. May 1, 1909. A cavalry detachment under the overall command of Ramon Falcon, Chief of Police, opens fire on a demonstration in Plaza Lorea. Several demonstrators are killed and many wounded. An ensuing General strike last nine days with over two-thousand arrests. November 13, 1909. Eighteen-year-old Ukrainian anarchist Simon Radowitzky throws a bomb at Falcon’s car, killing both Falcon and Falcon’s secretary. Due to his age, he will be sentenced to indefinite imprisonment. Martial law is declared and remains until January 1910. The offices and printing press of La Protesta are destroyed during this period. April, 1915. 9th Congress of FORA reverses their support for anarchist communism. A minority of members break away and form FORA V, remaining committed to anarchist communism. This is the FORA that appears in this book. The majority become FORA 1X. December, 1918. A strike breaks out at the Vasena metal works in Buenos Aires. January 2–14, 1919. Events take place that will become known as La Semana Trajica (The Tragic

Description: