The Air Force Can Deliver Anything, A History of the Berlin Airlift PDF

Preview The Air Force Can Deliver Anything, A History of the Berlin Airlift

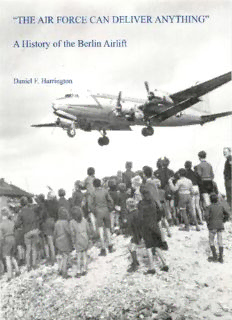

"THE AIR FORCE CAN DELIVER ANYTHING" A History of the Berlin Airlift Daniel F. Harrington FOREWORD The Berlin Airlift continues to inspire young and old as one of the greatest events in aviation history, but it was more than just an impressive operational feat. It was an unmistakable demonstration of the resolve of the free nations of the West and the newly independent United States Air Force to ensure freedom's future for the people of Berlin and all of us. That the first wielding of the military instrument in the post-WWII period was a humanitarian effort of historical proportions affrrmed the moral authority of men and women of good will. On the sixtieth anniversary of the Airlift, United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) rededicates this superb study as a tribute to the men and women whose efforts kept a city, a country and a continent free. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although only one name appears on the title page, many people made this study possible. I alone bear responsibility for its shortcomings; their efforts account for its merits. While I'll thank most of them in the conventional alphabetical order, I want to pay tribute to a special few first. They are the official historians who collected the documents, interviewed participants, and wrote the initial studies on which I've relied so heavily. My debts to them are immense, as a casual scanning of the footnotes will show, so it's fitting to list their names first: Ruth Boehner, Elizabeth S. Lay, Cecil L. Reynolds, William F. Sprague, Cornelius D. Sullivan, and Herbert Whiting. My debts to my contemporaries are equally great, especially to the other members of the USAFE history office. All of them gave unstintingly of their time to make this a better product. Bob Beggs and Ellery Wallwork read the drafts with the critical eyes of the top-notch professional historians they are. They made innumerable valuable suggestions and pinpointed many flaws. I'm also indebted to the USAFE Command Historian, Dr. Thomas S. Snyder, for giving me the opportunity to work on this study, for his critiques, and for all the support and encouragement he's given me. I especially appreciate the care he devoted to preparing the index. Our deputy command historian, Lois Walker, did an enormous amount of truly outstanding work turning a pile of paper into a real history. She designed the covers, scanned the illustrations and integrated them into the text, and put up with a stream of last-minute changes. Lois also caught errors and had many good ideas that improved the text, the appendices, and the other supporting material. She handled all aspects of getting the study published, from obtaining the funds to securing foreign disclosure review and working with graphics and the printer. I deeply appreciate her hard work, talent, patience, and professionalism. Many people outside the USAFE history office made valuable contributions. Sebastian Cox and his staff at the RAF Air Historical Branch were gracious hosts when I spent two weeks in London working through RAF records on Plainfare, and they have clarified many points for me since. Over the years George Cully has sent me a steady stream of citations and copies of Berlin material he came across in his own wide-ranging work in aviation history, including treasured copies of the booklet Dudley Barker wrote for the British Air Ministry in 1949 and the April 1949 special issue of Aviation Operations. Mike Dugre has responded patiently to a barrage of requests for ')ust one more" trip down the street to the Air Force Historical Research Agency to check one item or another. Ronald M. A. Hirst of Wiesbaden and Jim V Howard of the Agency staff helped immensely by providing accurate information on casualties. Betty Kennedy of the Air Mobility Command history office provided information on organizational issues and was a constant source of good ideas, advice, and suggestions. One of the greatest pleasures of working on this project was to share information, research leads, and ideas with Roger Miller of the Air Force Historical Support Office. Roger and I were graduate students together, and he's been working on a study of the airlift at the same time I've been writing this one. He helped me tremendously, sending me material I could not find in Germany, raising questions I had not thought of, and making me think more clearly about many issues. I'm sure I gained more from him than he gained from me. Last but not least, Al Moyers of the history office at the Air Force Communications Agency provided some of the photographs used here. There are others who deserve special thanks. I'm deeply grateful to John H. "Jake" Schuffert for permission to reprint a few of his classic cartoons from the Task Force Times and bring some life to these pages. I owe a large debt of gratitude to Lt Gen William J. Begert and the USAFE Command Section for their support in publishing this study. And last, those who are first in my thoughts and in my heart. I'm immensely grateful to my family, Sylvia, Beth, and Laura, for their love, support, and encouragement. D.F.H. Ramstein, Germany March 1998 I have made minimal changes for this new edition, correcting errors in the narrative and appendices. I have also updated the reading list. D.F.H. Langley AFB, VA January 2008 VI TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .......................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... v Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ vii List of Illustrations ......................................................................................................... viii Glossary ........................................................................................................................... ix Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Origins of the Blockade ................................................................................. 3 Chapter 2: The Air Forces Respond. .............................................................................. 15 Chapter 3: "I Expect You to Produce" ........................................................................... 43 Chapter 4: General Tunner vs. General Winter ............................................................. 71 Chapter 5: Winged Victory ............................................................................................ 87 Epilogue: The Legacy of the Berlin Airlift .................................................................. 103 Appendix 1: Berlin Airlift Summary ........................................................................... 109 Appendix 2: Berlin Airlift Fatalities ............................................................................ 111 For Further Reading ...................................................................................................... 115 Index ............................................................................................................................. 117 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Map, Germany during the Berlin Blockade ...................................................................... 2 Map, Occupied Berlin ....................................................................................................... 7 Photograph, Wiesbaden Air Base, 1946 ......................................................................... 19 Photograph, Rhein-Main Air Base, ca. 1948 .................................................................. 19 Photograph, C-47 s at Tempelhof. ................................................................................... 21 Photograph, C-54s at Tempelhof .................................................................................... 23 Photograph, Yorks at Gatow ........................................................................................... 24 Photograph, Sunderland Flying Boat in Havelsee .......................................................... 24 Photograph, C-47s at Tempelhof .................................................................................... 26 Cartoon, Rhein-Mud ....................................................................................................... 27 Photograph, Berlin women sweeping coal ..................................................................... 29 Photograph, Unloading flour in Berlin ........................................................................... 34 Photograph, Unloading coal in Berlin ............................................................................ 35 Photograph, PSP runway repair at Tempelhof. ............................................................... 37 Photograph, Lieutenant Gail S. Halvorsen ..................................................................... 39 Cartoon, Unloading during landing roll .......................................................................... 45 Drawing, How the Airlift Works .................................................................................... 46 Cartoon, Aerial tramway to Berlin. ................................................................................. 4 7 Cartoon, British and American cultural differences ....................................................... 51 Photograph, Triimmeifrauen at Tegel ............................................................................. 54 Photograph, Runway construction at Tegel .................................................................... 54 Photograph, Lancastrian tanker ...................................................................................... 63 Photographs, US commanders during the Berlin Airlift ................................................. 67 Cartoon, Ramming the Blockade .................................................................................... 70 Cartoon, The US Navy joins the airlift ........................................................................... 74 Photograph, First Hastings arrives in Germany .............................................................. 75 Cartoon, November fogs ................................................................................................. 7 5 Photograph, Tempelhof approach lights ......................................................................... 7 6 Photograph, CPS-5 radar ................................................................................................ 77 Cartoon, GCA controller. ................................................................................................ 78 Cartoon, Tour rotations ................................................................................................... 81 Photograph, Berlin unloading crew ................................................................................ 85 Photograph, Blockade ends, airlift wins ......................................................................... 86 Cartoon, Airlift Intrigue .................................................................................................. 91 Photograph, Tempelhof mobile snack bar ...................................................................... 95 Photograph, Rhein-Main operations, March 1949 .......................................................... 99 Photograph, Crew oflast Vittles flight ......................................................................... 102 Photograph, Tempelhof airlift memorial ...................................................................... 108 Photograph, Frankfurt airlift memorial ......................................................................... 108 Vlll GLOSSARY AACS Airways and Air Communications Service AACSW Airways and Air Communications Service Wing AAR After-Action Report AFHRA Air Force Historical Research Agency AMC Air Mobility Command App Appendix BAFO British Air Forces of Occupation CALTF Combined Airlift Task Force CUOH Columbia University Oral History Program EAC European Advisory Commission EUCOM European Command FO Foreign Office FRUS Foreign Relations oft he United States GCA Ground Controlled Approach Hist History HO History Office HQ Headquarters JCS Joint Chiefs of Staff LOCMD Library of Congress Manuscript Division MATS Military Air Transport Service MFR Memo for Record Mins Minutes MOD (United Kingdom) Ministry of Defence Mtg Meeting NA National Archives NAC National Archives of Canada NME National Military Establishment PA Public Affairs PLUME Pipeline under Mother Earth PLUTO Pipeline under the Ocean PRO Public Record Office PSF President's Secretary's Files PSP Pierced steel plank RAF Royal Air Force RG Record Group Rpt Report TFT Task Force Times TI&E Troop Information and Education us United States USAF United States Air Force USAFE United States Air Forces in Europe ix INTRODUCTION The Berlin Blockade was a defining moment in the Cold War in Europe. Moscow expanded its control throughout Eastern Europe after 1945, creating satellite regimes from Poland to Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. After Communists took power in Czechoslovakia in February 1948, the vortex of the East-West conflict shifted to Germany, where the Russians shared control with three other occupying powers— France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (US). The Soviets cut off road, rail, and barge traffic between Berlin and the Western occupation zones of Germany on 24 June 1948. The US and its allies apparently faced an inevitable choice between challenging the blockade on the ground, which might trigger a third world war, or withdrawing from the city, which would destroy American credibility in Europe, undermine the Marshall Plan, and open the way to Soviet political advances in Germany and the rest of Europe. The Berlin Airlift enabled the West to avoid this stark choice. Begun as an improvised stopgap to buy time, it evolved into an efficient organization that kept 2.2 million Berliners alive for nearly a year. The US nicknamed its part of the airlift “Operation Vittles,” while the British called theirs “Operation Plainfare.” Despite the different nicknames, the airlift succeeded because of teamwork. The British and American armies delivered food, coal, and dozens of other daily necessities to nine airfields in western Germany. From there, aircrews from the US Air Force, US Navy, Royal Air Force, and British civilian contract carriers flew cargoes into Berlin. The French provided land for a vitally important third airfield in the blockaded city. German and refugee laborers loaded and unloaded cargo. A network of support organi- zations that spanned two continents kept the planes in the air. Moscow may have counted on the Berliners to lose heart or winter weather to ground the airlift. Neither happened. In the famous “Easter Parade” of 16 April 1949, a plane landed in Berlin every 62 seconds. On 12 May 1949 the Russians gave up and reopened surface routes to the city. The airlift continued until 30 September, stockpiling supplies against a possible new blockade. By then the allies had flown about 2,326,500 tons of supplies to Berlin in just over 278,100 flights. The airlift inflicted an enormous defeat on Joseph Stalin. Not only had the Soviet leader failed to force the West out of Berlin, his pressure tactics had backfired. US credibility in Europe soared. The Western powers went ahead with plans to create the Federal Republic of Germany, which became a strong barrier against Soviet expansion. The Americans did not retreat from Europe, as Stalin hoped. Instead, the US and its allies established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in April 1949, while the blockade was still underway. For the next forty years, Berlin would be a potent symbol of the US commitment to Europe—and an equally potent symbol of the conflict between freedom and tyranny at the heart of the Cold War. 2 The Air Force Can Deliver Anything Germany during the Berlin Blockade CHAPTER 1 ORIGINS OF THE BLOCKADE The causes of the Berlin blockade can be grouped under two general headings: motive and opportunity. Taking them in reverse order, the Soviets’ opportunity was created during the Second World War, ironically enough in the form of an agreement with the powers Moscow would face during the crisis. In November 1944, a European Advisory Commission (EAC) composed of representatives of Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed on a plan to divide Germany into four occupation zones. (The allies later divided Berlin, Germany’s capital and most important city, into four sectors.)1 Even though Berlin was surrounded by the Soviet zone, the agreement did not spell out Western access rights to the city. There were several reasons for this omission. Everyone thought the zones would last a few months at best, until a peace conference drew up permanent arrangements for postwar Germany. In the meantime, the zonal boundaries were only to delineate where the various armies would be garrisoned. They were to have no political purpose or significance; victors and vanquished alike were to move freely across them. A January 1944 British proposal on which the EAC plan was based envisioned each country’s zone would have an international staff and token forces from the other allies. With Western forces moving freely throughout the Soviet zone, 1For the EAC and its plans for Germany, see Tony Sharp, The Wartime Alliance and the Zonal Division of Germany (London, 1975); Daniel J. Nelson, Wartime Origins of the Berlin Dilemma (University, Ala., 1978); and Avi Shlaim, The United States and the Berlin Blockade, 1948-1949: A Study in Crisis Decision-Making (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1983), 14-39. These books have largely superseded the pioneering studies of the access problem, Philip E. Mosely, “The Occupation of Germany: New Light on How the Zones Were Drawn,” Foreign Affairs, 28:4 (Jul 1950): 580-604; and William M. Franklin, “Zonal Boundaries and Access to Berlin,” World Politics, 16:1 (Oct 1963): 1-31. For the texts of the EAC protocols, see U.S. Department of State, Documents on Germany, 1944-1985 (Washington, D.C., n.d.), 1-9. The division of Berlin into sectors was at Soviet insistence. This worked against them during the blockade. Had they agreed to Western plans to rule the entire city in common, they could have interfered with the arrival and distribution of supplies. For the Soviet sector proposal, see U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1944, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C., 1966), 237-39 (volumes in this series hereafter cited as FRUS, year, volume).

Description: