The Ageless Gergel PDF

Preview The Ageless Gergel

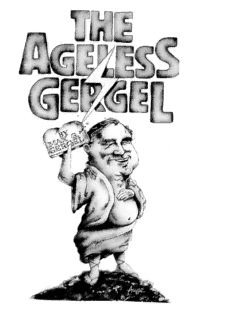

TO THE UNCAGED GERGEL: LONG MAY HE SING! If you already know Max Gergel, skip this preface. You'll want to get directly to the interesting part of this book. For that matter, if you don't know Max Gergel, you can also skip this preface with very little loss. It's a rather fulsome declaration of affection for one of the world's truly unique, truly unforgettable characters. Life with — or even near — Max is never boring. The man's vitality is downright awesome, as is his cheerful zest for living and his enormous affection for his fellow man (and woman!) If Max is somewhat slowed up (as he cheerfully complains) in his present "youthful old age," it's not readily apparent to most of his colleagues. He continues to maintain a level of personal and professional activity that would wear out most of us just contemplating his current international jet-hopping. I don't really think of Max as "growing" on someone — more accurately, he "explodes" on you and you are immediately a full- fledged family member for ever thereafter. In a way, it's rather too bad that Max chose Chemistry as a profession. From Max's many lectures, the world is only beginning to realize that it lost a world-class comic in the process. No matter how many times I hear the story of Preacher's unpublished synthesis recipes, I laugh anew. To hear Max tell of his adventures and misadventures with his family, his employees, the government, his neighbors, his competitors — anyone with whom Max has had an interface — is to be reminded of the human condition and (tragedies notwithstanding) how, in Max's hands, never-endingly interesting it continues to be. It's rather instructive to consider for a moment why Max is so good at entertaining us. It's not just the material—though Max clearly does have a thousand stories to tell us — but rather due to two special qualities that characterize his conversation: his impecable sense of timing (worthy of that of the master, Jack Benny) and the fact that the best of his stories are about people. I sometimes have my doubts as to whether they really are as interesting as Max makes them seem, but never-mind, just tell me more. Both of these features are clearly recognizable in this, the second of Max's books. The book is filled with fascinating anecdotes about interesting characters and Max's colorful style of writing — his choice of language, word order, sentence, sentence length, etc. — all add up to a kind of analogue of his style of speaking. Perhaps it's worth underscoring that the book was not written as 1 a sociological treatise, not as a literary exercise, nor for the analytical of mind, it was written as an act of sharing, to be enjoyed by his friends. Only Max could have written this book and I am grateful that he has done so. Live long and Prosper, Max — and, please, tell us all about it! JACK STOCKER Professor of Chemistry Louisiana State University - New Orleans This book is dedicated to some great men, gone forever and sorely missed: Dr. Charles Grogan General Mordechai Makleff Dr. Earl McBee Mr. Max Revelise Dr. Leonard Rice Mr. Jules Seideman Dr. Philip Zeltner R. LP. AUTHOR'S PREFACE I started this book in 1979 as a sequel to my first book, Excuse Me Sir, Would You Like to Buy a Kilo of lsopropyl Bromide which was printed by Pierce Chemical Co. and edited by my dear friend Roy Oliver, more because they liked me than with any thought of profit. I had written it within a year but spent four years correcting it and writing my third book, The Early Gergel. A group of my friends encouraged me to print the book myself and I aw indebted to Mr. Hiram Allen, President, Fairfield Chemical Co., Inc., Dr. Alfred Bader, Chairman, Aldrich Sigma, Dr. Roden Bridgwater, Maybridge Chemical Co., Pat Foster, PM Publishing Co., Jim Hardwicke, Hardwicke Chemical Co., Dr. James King, Army Chemical Center, Mr. Kermrt King, attorney at law, Dr. Ed Trueger, Trueger Chemical Co., Dr. Ed Tyczkowski, Armageddon Chemical Co., Mr. Joel Udell, Pyramid Chemical Co., Mr. George Yassmine, Marco Chemical Co., and Fred Zucker, Fluka U.S.A., for financially helping underwrite the book and giving me their encouragement. Giving unselfishly of their time have been my friends, excellent writers themselves, Kenneth Greenlee, Robert Murray, Steve Stinson and the late Philip Zeltner. These stories have benefited from their editing. I would like to thank my dear friend Elmer Fike of Fike Chemicals for helping me find Ron Gregory, who could translate the Iliad; John Auge, who did my illustrations; and Bookmasters of Ashland, Ohio and BookCrafters of Chelsea, Michigan, who actually put our work into a finished book. Elmer has always been prepared to take time from sailing his own ship to help me sail my own. The number of individuals and companies encouraging the effort are too numerous to list, Armageddon Chemical Co., Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Divex, Calabrian Corporation, Fairfield Chemical Co., Fertilizers and Chemicals Division of Israel Chemicals, Gaash/Sefayim Kibbutz, Holland Israel Chemicals Ltd., Giulini Chemicals, Mitsui, Moran Chemicals, Nir ltzhak Chemada, Wiley Organics who have employed me as consultant and encouraged my writing. Jack Stacker of LSU and his wife Katy have helped with the Introduction. Pat Foster has joined me on the many information gathering trips. My mother, Mrs. C. Jules Seideman, has liked everything I have ever written and Clive Gergel has done yeoman secretarial work. I also want to thank three typewriters which gave 4 their lives in this cause. It has been a lot of fun gathering stories and telling them and I hope those who read this book will enjoy and share my memories. »» S PROLOGUE The world of the child, of the young man, of the middle-aged, and of the old timer (lamentably I am a member of this last category is ever changing. I have visited Atlantic City where I lived when I was six years old, and found the streets closer together, the houses tightly packed, and distances much shorter than 50 years ago when I lived there. In 1927, my father had died, and my mother, only 26 years old, was dating a Mr. John D. McCauley, sales manager of the Norwich Pharmaceutical Company. He was a large man, well dressed and very old. I disapproved of my lovely young mother dating this white haired man, although he was good to me, brought presents, and slipped spending money into my hands. A conversation with my mother on the eve of my departure for Norwich Pharmaceutical Company 50 years later revealed that Mr. McCauley was about 40 when I knew him; 18 years younger than I am now. I was making a speech for the American Chemical Society, and Norwich was the host. I checked with them, but no one remembered John McCauley. A diligent search of old records indicated that he was in charge or Unguentine sales in 1928. "Sic transit...." In 1967,1 was 46 years ok), older than John McCauley when he courted my mama. I was president of one of the smaller chemical companies in Columbia, S. C, driven by fate to support three children and a collection of dogs and cats spread over three households. I also supported a number of charities that had my name on their lists, two lawyers, and a tailor. Harassed by all this supporting, I was losing weight. Israel, for whose Dead Sea Works Corporation I consulted, was about to have its "Six-Day War." I was heavily engaged in hostilities involving my second marriage. This in-between period was the "slack," as we say in sailing, during which tides, and often winds, shift. The chemical plant was doing neither better nor worse than usual. These were the halcyon days before the government commissioned an army of civil servants to regulate and nearly destroy the chemical industry. Because I did not make enough money at Columbia Organic Chemicals to support myself, children, lawyers, dogs and cats, I took other jobs to supplement my salary: consulting for Beaunit, Beau nit El Paso, Dead Sea Works and Chemetron Corporation. I gave talks for the American Chemical Society and rented what property I had left for whatever it would bring. This consisted of a dilapidated house at Lake Murray, still smelling doggy from its former tenants, a bungalow 6 at Lake Murray, which I had built five years earlier, and finally a beach house 185 miles from Columbia whose ownership I shared with Pat Gergel, about to become my second ex-wife. I had an old car, old clothes, an old sailboat and an old dog. I lived with my aunt, Mary Revelise, in the same house in which my grandmother and grandfather had lived before they died. My bedroom faced the highway, which permitted me to hear all the traffic of Rosewood Drive which rendered my sleepless and close to insanity. Fortunately I had a job as president of a small chemical company no one wished to buy, and my sardonic friend Alex Edelsburg, a warrior reduced to selling Fuller brushes. We passed the evenings with chess. I borrowed my philosophy from the Greeks. "Even this shall pass." Passing was my old friend Charlie Grogan, aged 47, his liver and kidneys, like those of most chemists, "et up." I consoled myself with the knowledge that my time of suffering would be short, and scanned the obituary columns to observe who had preceded me. I dispensed with women, devoting my remaining time to Science, good books and faithful friends. I purchased ear muffs and dug in to savor the tranquil life of the resigned recluse. Columbia Organic Chemicals in 1966 was run by good and faithful employees with much help from God. My mother and aunt Ida ran the "industrials" division which sold soap powder, insecticides and toilet bowl cleaner. My chief chemist was Tommy Jacobs, who supervised production of our organic chemicals. My office, directed by Mrs. Jean Culley, ran about the same whether I came to work or not. The buildings were separated from the rest of Cedar Terrace by a large unclimbable fence (I climbed it on one occasion when I forgotten my keys, and nearly lost my...well, everything). This protected my mother's 50 or so cats from Cedar Terrace dogs and children, and vice versa. During the preceding, troubled year I had neglected the little company to mull over my personal woes. Now, having reached personal peace, it was necessary to devote more time to the company or I would be a starving recluse. One can tolerate an empty heart, but it is difficult, especially for me, to tolerate an empty stomach. 7 Chapter 1 Columbia Organic Chemicals in the early days had an unusual working staff. Out of gratitude for past services, I maintained the lame and the halt, almost all past their best performance. New employees were the dropouts and those fired by larger, local chemical companies, or those between jobs, or the very young, wishing to gain industrial experience. A young man from one of Columbia's "better families," who toyed with the idea of adopting chemistry as a career, was in the latter category. He was tall, athletic, handsome, clean-cut, wealthy, polished and ambitious. For his first assignment he was to synthesize n-butyl mercaptan, a severe test for the budding chemist. It has a very bad odor, eau de Ia skunk. If he survived this, I would let him make an explosive, and then, after a few weeks would put him on regular production items most of which are toxic. My novice successfully made n-butyl mercaptan. He visited me at lunch time, stinking to high heaven, announced that he had changed his mind, and his ambitions. His mother telephoned after he went home to tell me that she had burned his clothes and consulted a local law firm. His uniform was returned by taxicab-coJIect. The cab driver furtively smelled his armpits while I borrowed enough money from the fellows to pay the fare. The uniform fitted another employee. Yet another employee, of about the same size, appropriated the departed's street clothes. He emerged five minutes later from the bathroom, which was also our dressing room, clad in shirt and sweater, blazoned with "Forest Lake Country Club," tennis shoes, and an ascot. Nonchalantly, the two men continued the synthesis abandoned by our former employee. The lawyers decided not to sue. Our men in 1967 routinely made evil smelling compounds and did not need uniforms. They could be picked out in any gathering by smell and appearance. We had some fascinating chaps. Preacher, who made our 2,3- dichloropropene left us when his second wife found him living with his future third. He declared, "It's cheaper to live in jail, Mr. Max." They all called me "Mr. Max." Bobby, who started with us when he was 16 years old and lasted for 20 years, could make bird songs through his teeth, attracting the plant felines, who followed him across the yard. They assumed he had birds in his pockets. Bobby was from infancy a devotee of John Barleycorn, and under his influence destroyed 8 many automobiles. He would come to work on Friday, already "under the weather," draw his pay (his creditors were in the car that brought him to the plant), distribute the money, reel into my office, thank me for my generosity and friendship, and beg for an advance on next week's pay. With the passage of time, Bobby's visit moved up a day and the amount of his paycheck diminished inversely in proportion to the quantity he drank. His personal debt to the boss steadily increased. When Steve Reichlyn took over as president of the company in 1978, Bobby was "knocking off" by Wednesday. He was at this time 40 years old and looked 60. His liver was amazing and when he took early retirement to have more time for serious drinking, he died not from drink but because a disagreement with one of his friends culminated with weapons. Then there was General Robert E. Lee Jones (sic), not only a good bench chemist, but a latent thespian. One day he was assigned to crank the soap machine (in the early days it was cheaper to pay a worker than to buy equipment), and he emerged from the soap room bellowing, "I injured my privates." He was already the admiration and source of secret envy among his peer group for his use of them. Aside from possible legal problems should he sue, there was the possibility of bodily harm to Columbia Organic's president by some irate, frustrated sweetheart thwarted by our soap machine. We rushed him to Jack Alion's office and the next day Dr. Alion called to allay my fears. General Robert E. Lee Jones had clap. Cur soap machine was innocent. A survivor from many years' employment, Leon Hines, is still with Columbia. Fifteen years ago he was my height, heavy set and strong. He has not changed. Leon has a wonderful smile. In addition to being the plant's truckdriver for pickup and delivery, he works in the laboratory and helps make chemicals. He is my mother's amanuensis, i.e. he is cat feeder and cat cleaner-upper. The cats are fond of Leon, my mother is fond of Leon. He has been my faithful attendant during three marriages and as many divorces, keeping my quarters clean, gathering things to be washed and pressed, vacuuming bachelor quarters, and feeding dogs and cats left from aborted marriages. Leon is a Moslem and does not eat pork. He works hard for the plant, my mother and me, tireless and ever smiling. Thomas Jacobs was recruited by Bobby. Tommy had just completed service in Korea and he joined Bobby and me in our jugwashing business. We drove the plant truck to various drug stores and picked up crates of empty Coca-Cola syrup jugs, washed the jugs, and sold them to Columbia Organic Chemicals to be used as 9

Description: