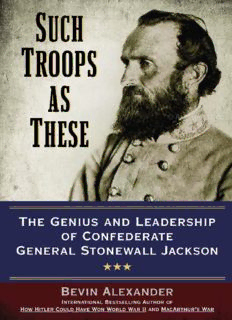

Such troops as these : the genius and leadership of confederate general stonewall jackson PDF

Preview Such troops as these : the genius and leadership of confederate general stonewall jackson

CONTENTS Title Page Copyright List of Maps Acknowledgments INTRODUCTION: Jackson’s Recipes for Victory CHAPTER 1: The Making of a Soldier CHAPTER 2: “There Stands Jackson Like a Stone Wall” CHAPTER 3: Jackson Shows a Way to Victory CHAPTER 4: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign CHAPTER 5: The Disaster of the Seven Days CHAPTER 6: Finding a Different Way to Win CHAPTER 7: Second Manassas CHAPTER 8: Calamity in Maryland CHAPTER 9: Hollow Victory CHAPTER 10: The Fatal Blow EPILOGUE: The Cause Lost Selected Bibliography Notes Index MAPS Eastern Theater of War 1861–1865 Winfield Scott’s March on Mexico City 1847 First Manassas July 21, 1861 Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign 1862 The Seven Days Battles June 26–July 2, 1862 The Second Manassas Campaign July 19–September 1, 1862 Battle of Second Manassas The First Day, August 29, 1862 Battle of Second Manassas The Second Day, August 30, 1862 The Antietam Campaign September 3–20, 1862 Battle of Antietam September 17, 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg December 13, 1862 The Chancellorsville Campaign April 27–May 6, 1863 The Gettysburg Campaign June 10–July 14, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg July 1–3, 1863 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Natalee Rosenstein, vice president and senior executive editor of the Berkley Publishing Group, for her splendid, insightful, and discerning support of this project. It has been a pleasure working with her and with Robin Barletta, editorial assistant at Berkley. Robin is a most remarkably sensitive, understanding, and efficient person who expedited the project most wonderfully. She corrected all my errors, removed all roadblocks, and turned the entire endeavor into an adventure. Richard Hasselberger produced a superb cover design that conveys the content of the book most effectively. Laura K. Corless conceived a tasteful and truly beautiful design for the interior text. My longtime cartographer, Jeffrey L. Ward, drew the exceptionally accurate maps that allow the reader to follow exactly where the actions took place. Clear and comprehensible maps are mandatory for understanding military operations, and Jeffrey, in my opinion, draws the best maps in America today. I have relied for a long time on my agent, Agnes Birnbaum, for her friendship, sage advice, and surpassing knowledge of the publishing industry, but mostly for the inspiring example she presents of a caring and considerate human being. Finally, I am most honored that my sons Bevin Jr., Troy, and David, and my daughters-in-law, Mary and Kim, have always supported me steadfastly in my long and exhausting writing ventures. INTRODUCTION Jackson’s Recipes for Victory Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson was a unique, incredibly complicated figure. He was committed to his Presbyterian religious faith, devoted to his second wife, so reserved that even his close friends seldom knew what he was thinking, dedicated to duty and the cause of Southern independence, and by far the greatest general ever produced by the American people. Very early, Jackson discerned a way for the South to win the Civil War with speed and few losses. He recognized that the North, with three times the population of the South and eleven times its industry, was so sure of victory that it had sent practically all of its military forces into the South and had left the North almost entirely undefended. The only thing the South had to do to win, Jackson saw, was to invade the eastern states of the Union, where the vast majority of Northern industry was located and where most of its population resided. Before any Union armies could be extricated from the South, Confederate troops could cut the single railway corridor connecting Washington with Northern states, force the Abraham Lincoln administration to abandon the capital, and, by threatening the railroads, factories, farms, and mines along the great industrial corridor from Baltimore to southern Maine, compel the Northern people to give up the struggle. A similar assault on Southern economic prosperity was precisely the strategy that Lincoln was using to conquer the South. But the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, was a decidedly third-rate leader who possessed extremely little vision or imagination. He was committed to passive defense of the South, despite the fact that it was guaranteed to fail.1 Davis refused to endorse Jackson’s strategy, although he pressed it on Davis four times. Once Jackson realized that Davis was never going to authorize a decisive invasion of the North, he developed another method of winning the war. He saw that two new weapons had made attacks against defended positions almost certain to fail. The first weapon was the single-shot Minié-ball rifle, with a range four times that of the old standard infantry weapon, the smoothbore musket. The second was the lightweight “Napoleon” cannon (named after Napoleon III, not the emperor) that could be rolled up to the firing line and could spew out clouds the emperor) that could be rolled up to the firing line and could spew out clouds of deadly metal fragments called canister into the faces of advancing enemy troops. Jackson saw that the South could be victorious if it induced Northern armies to attack well-emplaced Confederate positions. The Union armies would inevitably be defeated, and the Confederates could swing around the flank of the demoralized Northerners and force them into retreat or surrender. None of the other commanders on either side identified the revolutionary implications of these two weapons, however, and Jackson had an extremely difficult time trying to convince the senior Confederate commander in the East, Robert E. Lee, to follow his new system. Jackson recognized that there is only one fundamental principle of military strategy, or the successful conduct of war. It is to attack the enemy where he is not. That is, to exert force where there is little or no opposition. All the other axioms of warfare can be reduced to variations on this single elementary theme. The ancient Chinese military sage Sun Tzu encapsulated the idea in a single sentence around 400 B.C.: “The way to avoid what is strong is to strike what is weak.”2 Jackson knew nothing of Sun Tzu, but he developed the same understanding on his own. This is an extremely difficult concept to get across, however. Warfare to most people does not seem to be so simple. They view it through the lens of very different experiences. Human beings built their concept of warfare in the Stone Age. The small bands and tribes into which the human race was divided found that direct confrontation was the most likely way to deter opposing bands and tribes from encroaching on their safe havens and hunting grounds.3 We have carried this concept of frontal challenge forward into modern times. It is deeply ingrained in the human psyche. We label persons who act otherwise as sly and shifty; we say that they blindside other people, that they stab them in the back. We revile and despise such people, while we admire people who act in a direct, straightforward manner. Over the aeons, highly observant individuals have occasionally seen, however, that indirection is the most effective way to achieve success, in military and in other matters, and they have attacked their opponent’s weakness. But these have been rare occurrences. In times of stress we usually revert to the instinctive response we learned in the Stone Age. We challenge the opponent right in front of us. Therefore it is the extraordinary person who can avoid straight confrontation and can recognize the wisdom of Sun Tzu, who said: “All warfare is based on deception.”4 Stonewall Jackson was such an extraordinary person. And he saw clearly ways to win by going around the enemy, not confronting him headlong.

Description: