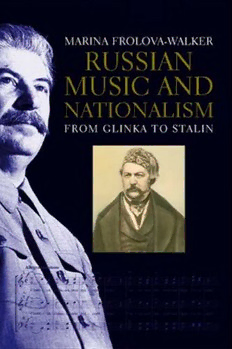

Russian Music and Nationalism: From Glinka to Stalin PDF

Preview Russian Music and Nationalism: From Glinka to Stalin

RUSSIAN MUSIC AND NATIONALISM RUSSIAN MUSIC AND NATIONALISM FROM GLINKA TO STALIN MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN AND LONDON Copyright © 2007 by Marina Frolova-Walker All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S, Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. For information about this and other Yale University Press publications please contact: U.S. Office: [email protected] yalebooks.com Europe Office: [email protected] www.yalebooks.co.uk Set in Minion by J&L Composition, Filey, North Yorkshire Printed in Great Britain by St Edmundsbury Press Ltd, Bury St Edmunds Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Frolova-Walker, Marina. Russian music and nationalism from Glinka to Stalin/Marina Frolova-Walker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11273-3 1. Music—Russia—History and criticism. 2. Nationalism in music. I. Title. ML300.F76 2007 780.947'09034—dc22 2007033565 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library 10 98765432 1 CONTENTS Preface vii 1 Constructing the Russian national character: literature and music 1 2 The Pushkin and Glinka mythologies 52 3 Glinka’s three attempts at Russianness 74 4 The beginning and the end of the Russian style 140 5 Nationalism after the Kuchka 226 6 Musical nationalism in Stalin’s Soviet Union 301 Notes 356 Glossary of names 380 Index 396 To the memory of my father PREFACE Every Russian, listening to this or that piece of music, has more than once had a chance to say: “Ah, this is something Russian!” Vladimir Odoyevsky Over the past century and a half, Western audiences, like Odoyevsky, have more than once had the opportunity to say “Ah, this is something Russian!” Russian classical music is now a ubiquitous presence in the world’s concert halls, and with increasing frequency in the opera houses. The mystique of the music’s “Russianness” is a powerful selling point, now as much as ever. For more than ten years, as a Russian in the West, I have attempted to speak and write about Russian music without taking advantage of this mystique; indeed, on the contrary, I have frequently discussed the process of mystification in the open, in order to undermine its hold on the musical public, and even on surprisingly many musicologists. This book is a summation of these efforts. But although this mystification takes its own shape in the West, it is not simply a Western invention. As a music student in Russia, from school, through music college to conservatoire, I found one aspect of the musical education system increasingly frustrating: Russian classical music was taught as if it had arisen and flourished quite independently of Western music. The categories under which Western music was commonly discussed, such as counterpoint or sonata form, were considered only tangentially relevant to Russian music, which was discussed in relation to folksong and narodnosf (nationality). Russian music was regarded as a separate tree, with its roots firmly planted in Russian soil. It had its own, internal network of references and its own value system. I sometimes idly wondered what Western music education had made of Glinka, the great “father of Russian music”. Was he regarded as a Beethoven, or a Liszt, or merely a Spohr? But it was considered unwholesome to raise such questions, and the Western and Russian music viii RUSSIAN MUSIC AND NATIONALISM departments continued along their separate paths, meeting only in the conservatoire canteen for lunch. When I chose to pursue my career in the West, I was soon able to find the answer to such questions: for university students in the United Kingdom, where I was now based, or in the USA, I found that Glinka was a non-entity. And not only Glinka, but every other Russian composer until Stravinsky, who was regarded as a special case. When Musorgsky or Shostakovich made an appearance on rare occasions, they were relegated to specialist options for final-year students, an eccentric dessert rather than a solid, nutritious main course. The mystique that worked prodigiously well for concert promoters from Diaghilev onwards, was clearly poison in the more rarefied atmosphere inhabited by students and academics. Against this bizarre dichotomy in the West, the only alternative seemed to be the bloated and complacent nationalism of the Russian approach. I found both distasteful and ultimately wrong-headed, and I set myself the task of helping to construct a more considered discourse on Russian music, avoiding both mystification and its twin, disdain, in order to bring Russian music within the proper remit of musicology or the broader field of cultural studies. It would be ungracious, of course, for me to give the impression that I was alone in such endeavours. Musicology in the English-speaking world was undergoing radical changes at the time when I left Russia. While some of these changes turned out to be no more than passing fads, there have been substan tial and lasting consequences of this upheaval, not least an openness to the questioning of former prejudices. Foremost among those musicologists who promoted this new openness and questioning was Richard Taruskin, whose inspiring volume Defining Russia Musically made musicologists in the West take Russian music much more seriously, and is currently exerting its influ ence even among Russian musicologists. But the task of dispelling both mystique and hostile prejudice - two sides of the same coin - is nowhere near accomplished. Historians of nationalism from Eric Hobsbawm nearly half a century ago to Benedict Anderson in recent years have been busy exposing the fraudulent origins of nationalist and imperialist myths. But these myths are not simply honest conceptual errors, to be abandoned once they are intellec tually defeated. Politicians and the media, both in the West and in Russia, have been rebuilding them over the past decade-and-a-half. Yet for many years such myths were widely considered alien or repugnant after decolonization and defeat in Vietnam, while in the East, for a briefer period, Russians had to come to terms with defeat in Afghanistan and the loss of Russia’s Soviet empire. But now official rhetoric once again tells us of “new-caught sullen peoples, Half devil and half child” as Kipling’s “white man’s burden” re-enters not merely conservative but also liberal discourse. The purpose of this volume is to a large PREFACE ix extent to demonstrate how such myths are bom and perpetuated, how they flourish and reach the stage of self-defeating absurdity, how they can die off only to be resurrected in an instant. Thus the story of Russian musical nationalism should begin from its central myth, that of the Russian national character, or “Russian soul” as it is usually called. Chapter 1 serves, in part, as a foundation for the later chapters, since it examines the evolution of the national-character myth in Russia. The idea that nations, like individuals, have varied and distinctive characters, was first developed and incorporated into an elaborate ideology by Herder, inaugu rating what we now call Romantic nationalism. The national-character myth has dominated the reception and historiography of Russian music for the past two centuries, beginning from the premières of Glinka’s Russian operas, through to the commercial success of Russian concert music in the West during the twentieth century. For those who cling to a belief in the Russian soul (sometimes beneath a rational veneer), it will come as a surprise that as late as the 1830s the Russian intelligentsia could not describe any such entity, although they certainly sought after it. By this time, Herderian ideas had been already become quite widespread in Europe, and the European elites thought they knew what “a true Frenchman” or “a true German” was. It was only over the next four' decades that a stereotype was slowly constructed, largely through the works of literary figures in the two generations following Pushkin. Russians came to define themselves in opposition to “Europe” or “the West”, and they saw them selves endowed with melancholy or even tragic soul that searched, however, vainly, after ultimate truth, as against a supposed Western focus on whatever was commercially expedient. But in rational terms, this can be seen as the self- portrait of a declining class filtered through European Romanticism; that class was the Russian gentry, which was no longer able to sustain its old ways after centuries of dividing up estates among successive generations of sons. But this principal version of the Russian national character, generated through literature, is not necessarily reflected in Russian nationalist music. At first, among Glinka’s contemporaries, there was a certain reciprocation between musicians and writers in constructing the melancholy aspect of the stereotype, but after Glinka, and indeed because of him, the two arts diverged sharply. In the works of The Five (or the “Kuchka”, to use their Russian sobriquet) a very different image of the Russian soul was constructed, not on the inward gaze of the nineteenth-century intelligentsia, but rather on the intelligentsia’s idealizations of “the people” (consisting of peasants, rather than urban workers). This image was accordingly much more sanguine and robust and, for lack of inspiration in contemporary reality, it was firmly rooted in an epic past.