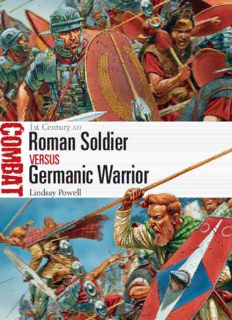

Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD PDF

Preview Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD

1st Century AD Roman Soldier VERSUS Germanic Warrior Lindsay Powell ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com 1st Century ad Roman Soldier Germanic Warrior Lindsay PPoowweellll ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION 4 THE OPPOSING SIDES 10 Recruitment and motivation (cid:116) Morale and logistics (cid:116) Training, doctrine and tactics Leadership and communications (cid:116) Use of allies and auxiliaries TEUTOBURG PASS 28 Summer AD 9 IDISTAVISO 41 Summer AD 16 THE ANGRIVARIAN WALL 57 Summer AD 16 ANALYSIS 71 Leadership (cid:116) Mission objectives and strategies (cid:116) Planning and preparation Tactics, combat doctrine and weapons AFTERMATH 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 78 INDEX 80 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com Introduction ‘Who would leave Asia, or Africa, or Italia for Germania, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?’ (Tacitus, Germania 2). This negative perception of Germania – the modern Netherlands and Germany – lay behind the reluctance of Rome’s great military commanders to tame its immense wilderness. Caius Iulius Caesar famously threw a wooden pontoon bridge across the River Rhine (Rhenus) in just ten days, not once but twice, in 55 and 53 bc. The next Roman general to do so was Marcus Agrippa, in 39/38 bc or 19/18 bc. However, none of these missions was for conquest, but in response to pleas for assistance from an ally of the Romans, the Germanic nation of the Ubii. It was not until the reign of Caesar Augustus that a serious attempt was made to annex the land beyond the wide river and transform it into a province fit for Romans to live in. Successive explorations had established its boundaries: Germania is separated from the Galli, the Raeti, and Pannonii, by the rivers Rhenus and Danuvius [Danube]; mountain ranges, or the fear which each feels for the other, divide it from the Sarmatae and Daci. Elsewhere ocean girds it, embracing broad peninsulas and islands of unexplored extent, where certain tribes and kingdoms are newly known to us, revealed by war. (Tacitus, Germania 1) However, its scale eluded the geographers of the Ancient World, including the best minds Agrippa had brought together to compile a ‘Map of the World’ (Orbis Terrarum): … the dimensions of its respective territories it is quite impossible to state, so immensely do the authors differ who have touched upon this subject. The Greek writers and some of our own countrymen have stated the coast of Germania to be 2,500 miles in extent, while Agrippa, comprising Raetia and Noricum in his estimate, makes the length to be 686 miles, and the breadth 148. (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 4.28) 4 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com Such inaccurate measurements made military planning problematic from the outset. When compared to Agrippa’s combined measurement of the three conquered provinces of Aquitania, Belgica and Gallia Comata or ‘Long Haired Gaul’ (420 Roman miles long by 318 miles wide), the whole of Germania was only eight times greater. It had taken the army of Iulius Caesar just nine years to reduce these Three Gallic Provinces (Tres Galliae). Hispania had taken 200 years. On that basis the conquest of Germania seemed an attainable objective. In 17 BC an alliance of Tencteri and Usipetes nations led The land was inhabited by a patchwork of tribal nations (nationes). The by warchief Maelo of the Romans referred to them collectively as Germani, but they identified Sugambri raided into the themselves by tribal names. Some – like the Sugambri – were related to the Roman province of Gallia Iron Age Celts who inhabited Gaul, while others, such as the Cherusci, shared Belgica. Encountering them by chance, the governor Marcus a different cultural and linguistic tradition called Germanic. Some nations Lollius was ambushed and were ruled by kings, while others were collectives that elected their leaders. the eagle standard of Legio V Most people lived relatively independently with their families on farms, rather Alaudae was captured by the than in towns, though at least one is known: Mattium, the capital of the Germans. The event became known as the Clades Lolliana Chatti (the location of which remains obscure). – ‘Lollian Disaster’. It was the During the reign of Augustus (27 bc–ad 14), the basic unit of the Roman trigger for Caesar Augustus to Army (exercitus) was the legion, derived from the Latin word legio meaning embark on a re-assessment of ‘military levy’. Soldiers (legionarii) for the army were recruited exclusively north-western border security, leading to the conception from male citizens principally from Italy, but their numbers were increasingly of a war to annex Germania. augmented by volunteers (volones) from the provinces. There were 28 legions This 19th-century painting by of 5,600–6,000 men each in service at the start of ad 9. Additionally there Friedrich Tüshaus romantically were elite Praetorian Cohorts – initially nine, but rising to 12 in the later part evokes a clash on the banks of the Rhine between the of Augustus’ principate – perhaps representing 12,000 men in all, located Roman Army and Germanic at camps around Italy. To supplement the ranks of the Roman legions, warriors, complete with non-citizen allies from outside the empire were recruited and formed their anachronistic winged own units (alae, cohortes) of 500 or 1,000 men each. These ethnic auxiliary helmets. (Public domain) 5 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com tttroops were particularly important for providing specialist infantry, such as archers (sagittarii) from Crete and cavalry (turmae) from the foothills of the Alps. Several Germanic nations served the Roman army in this capacity, often under their own chiefs. Among them were the Batavi, Chauci, Cherusci, Frisii, Sugambri and Ubii. The exact number of auxiliary units in service at the start of ad 9 is not known, but they made up about half of Rome’s total military forces. A permanent fleet of ships (classis) for sea patrols was based at Misenum ooon the Bay of Naples to patrol the sea-lanes used by grain ships sailing bbbeeetttwwween Italy, Africa, Sicily and Egypt. A fleet was located at Ravenna, which ppaattrroolled the Adriatic coastline, and another – established by Drusus the Elder Nero Claudius Drusus in 13 or 12 bc – operated from several bases along the Rhine to assist the army (Drusus the Elder) led the first of Germania with its operations. At full strength the combined manpower of serious attempt at conquering legionary, Praetorian, auxiliary and marine forces may have amounted to Germania for the Romans. In preparation for his campaigns 300,000–330,000. In ad 9 about one third were stationed at forts along the in 14 BC he founded legionary Rhine or its tributaries. Rome’s emerging German province and its borderlands fortresses whose locations on were home to a diverse community of many different nations. the Rhine became permanent The catalyst for the outright conquest of Germania appears to be a raid bases and then important cities of the empire, and have by an alliance of German nations under the leadership of Maelo of the survived to our own day. After Sugambri, in 17 bc. By chance they encountered and ambushed the Roman his death following a riding governor (legatus Augusti pro praetore) and his Legio V Alaudae, taking the accident in 9 BC, the Senate legion’s eagle standard (aquila) as a trophy. The humiliation became known posthumously awarded him the honorary war title as the ‘Lollian Disaster’ (Clades Lolliana). The following year Augustus Germanicus, meaning ‘the replaced his governor with his eldest stepson (and future emperor) Tiberius German’ or ‘of Germania’. His Claudius Nero, and joined him in person in Gaul to carry out an assessment sons were permitted to adopt and lay down plans for war. In preparation for it, in 15 bc Augustus’ youngest the title. This gold aureus was minted by his youngest son, stepson, Nero Claudius Drusus (Drusus the Elder), was given command Emperor Claudius. (Harlan J. of an army and with it he annexed the territory of the Raeti in northern Berk. Author’s collection) Italy and the central Alps, and that of the Vindelici in the Bavarian Voralpenland. The next year Drusus the Elder assumed the governorship of the Three Gallic Provinces and with it responsibility for prosecuting the war in Germania. In one of the largest construction projects of the Augustan Age, Drusus’ legionaries spent two backbreaking years building military infrastructure comprising five legionary fortresses and a connecting road along the Rhine, a system of canals (fossa Drusiana) connecting the river to the Lacus Flevo (Zuiderzee/IJsselmeer) and a fleet of tubby barges and troop transports. After months of preparation in the spring of 12 bc the offensive was launched. Drusus led his expeditionary force of seven legions in a series of annual campaigns – including an amphibious landing in the Ems estuary – moving eastwards from the Frisian coast towards the River Elbe (Albis). Only the accidental death of the commander in late 9 bc prematurely ended what had been a successful campaign. His brother Tiberius assumed the task of completing the war. Between 8 and 7 bc he led expeditions, notably achieving the surrender of Maelo and forcible relocation of the Sugambri, but by then it was becoming evident that many of the free people of Germania would not kowtow. The Romans formed alliances with several nations, among them the Cherusci, and received hostages. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus – consul of 16 bc and grandfather 6 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com of the future Emperor Nero – was the first Roman general to lead an army across the Elbe, in ad 1 or 2. As the first governor of the province Germania, he established its administrative capital at Ara Ubiorum (modern Cologne), the town constructed for the Ubii. At an altar dedicated to Rome and Augustus, delegates of the Germanic nations met in council to discuss matters affecting their communities under the aegis of a priest of German birth, Segimundus (AKA Segimund) of the Cherusci. War broke out again in ad 4 and 5 and Tiberius returned to squash the insurrection. By ad 9 the province was undergoing a standard process of transformation. The legionaries began constructing a network of roads to connect military bases and laying out urban civilian settlements to host markets and courts to adjudicate in legal disputes. The aristocracies of the subject nations were being granted titles and limited powers of self-government within the Roman federal system and encouraged to resettle in towns. Having decision-making power (imperium) granted him by the emperor and with substantial military resources at his disposal, the then governor Publius Quinctilius Varus was responsible for driving the process of nation building, for ensuring internal security and protecting the interests of its Roman citizens. He was keen to see it through. According to the most complete account to come down to us, the process This silver denarius minted of transforming the territory into a province before Varus became governor was in about 10 or 9 BC depicts a barbarian adult handing proceeding at its own pace. The Germanic nations were adapting gradually to over a child into the care of the changes being introduced by the Roman authorities. When Varus took Augustus who is seated on office, however, that policy changed. ‘In the discharge of his official duties,’ a curule chair. Exchanging writes Cassius Dio, Varus ‘was administering the affairs of these peoples also, he hostages between enemies was a common practice in strove to change them more rapidly. Besides issuing orders to them as if they both Germanic and Roman were actually slaves of the Romans, he exacted money as he would from subject societies. After surrendering nations’ (Roman History 56.18.3). He continues, ‘To this they were in no mood to Tiberius in 7 BC chief to submit, for the leaders longed for their former ascendancy and the masses Segimerus of the Cherusci handed over his sons preferred their accustomed condition to foreign domination’ (Roman History Arminius and Flavus to 56.18.4). Even so, the Germanic nations remained a disunited force. With the Roman commander. roughly 30,000 legionaries and large numbers of auxilia deployed across the They were educated in region, individually the German nations could not oust the Romans. To rally Rome, raised as members the anti-Roman sentiment the Germans needed to unite behind a single leader of the Equestrian Order and trained to lead ethnic units with a plan. According to Cassius Dio the German attack on the army of of infantry, cavalry or both. Quinctilius Varus was the vision of Arminius and his father Seggimeruus (Kenneth J. Harvey. Author’s (AKA Segimer) of the Cherusci nation. collection) Segimerus had entered into a treaty with the Romans and had hhhaannddeedd over his sons as hostages. Both were repatriated to Rome, where they llleeaarrnneedd Latin and Roman ways. Admitted as Roman citizens into the Equuueessttrriiaann Order, when old enough they became soldiers in the service of RRRoommee,, probably as praefecti of ethnic Cherusci cavalry. Velleius Paterculus stttaatteess that Arminius ‘had been associated with us constantly on privvvaattee campaigns’ (Roman History 2.118.2) which some interpret to mean tthhee Great Illyrian Revolt (ad 6–9) in the western Balkans. What pricked Arminius’ conscience, turning him from a man enjoyyyiinngg the privileges of Roman civilization to a German patriot, is not preseeerrvveedd in the extant accounts. At some point he realized he should lead a naaattiioonnaall revolt, using his knowledge of Roman warcraft against them. Howww ffaarr iinn 77 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com Rome’s German frontier,AD9 The Roman province of Germania extended from the Rhine (Lupia) and Main (Moënus) rivers. Its effort had shifted as far west as the Wadden Sea and as far east as the from war fighting to peace making, and was constructing Elbe. It was the product of two decades of concerted a network of roads to connect the camps with stations and military campaigns, beginning with Nero Claudius Drusus watch towers distributed across the newly occupied territories Germanicus (12–9 BC), continuing with his brother Tiberius at the Germans’ request, according to Dio. He also mentions Caesar (8–7 BC, AD 4–5) and concluding with Lucius Domitius civilian centres in Germania at this time, one of which – Ahenobarbus (1 BC–AD 2), who resettled the Hermunduri and, Waldgirmes in the Lahn Valley – has been identified, having ‘crossed the Elbe, meeting with no opposition, had and others may yet remain to be discovered. made a friendly alliance with the barbarians on the further Assisting in the process were pro-Roman allies, among side’ (Dio, Roman History 55.10a.2). He also moved the them the Angrivarii, Batavi, Cananefates, Chauci, Cherusci, province’s administrative centre from Vetera (Xanten) to Cugerni (the forcibly relocated Sugambri) and Frisii. As part Ara Ubiorum (Cologne). of their treaty obligations, these nationes provided men and Publius Quinctilius Varus was appointed as legatus matériel for the Roman army. Though tipped off to expect Augusti pro praetore of Germania in AD 6 to promote the trouble at the end of the summer of AD 9, Varus was unwilling process of assimilation of the nations within its boundaries. to believe the Germanic peoples were going to rise in revolt. Under his command were five legions and an unknown Arminius had assembled a formidable coalition of Angrivarii, number of auxiliary cohorts and alae. The Roman army had Bructeri, Chatti, Chauci and Marsi to join his own Cherusci. moved successively from its original winter quarters of 12 BC Having signed a treaty with Tiberius in AD 6 the Marcomanni on the Rhine to new bases along the courses of the Lippe refused to join him. advance the preparations for the uprising were made is not known. Arminius, meanwhile, had to convince his own people and others to rally behind him. Paterculus writes, ‘At first, then, he admitted but a few, later a large number, to a share in his design; he told them, and convinced them too, that the Romans could be crushed, added execution to resolve, and named a day for carrying out the plot’ (Roman History 2.118.3). In his favour, Arminius enjoyed the complete trust of the governor. Key to the success of the revolt was to create a deception so convincing that Varus would believe it and not suspect his Cheruscan officer of treachery, then follow him on an unfamiliar route, whereupon his army would be ambushed. He knew that the Roman army would need to return to its winter camps at the end of the season, and that the legions were most vulnerable on the march. To reduce their numbers, the Germanic communities asked for Roman troops to be billeted with them, ostensibly to provide security and intervene in disputes. The trap was set for a day in the late summer of ad 9. There was a tense moment when the plot was exposed. A noble of the Cherusci, Segestes, had learned of a deception planned by Arminius and Segimerus, and had gone straight to the governor. He disclosed everything he knew and demanded that the conspirators be arrested and clapped in chains. To his great surprise Varus not only refused to believe the informant ‘but actually rebuked him for being needlessly excited and slandering his friends’ (Cassius Dio, Roman History 56.19.3). In the weeks before the assault the father-and-son team had gone to great lengths to ingratiate themselves with Varus. They arranged to be close to him at all times and had shared meals with him, reassuring him that they would do everything demanded of them. They were the model barbarians. Their ploy worked. Varus’ refusal to believe the tip-off from a credible source reassured the schemers and prompted them to move ahead with their plan. 8 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com Mare Germanicum Wadden Sea CHAUCI GE R FRISII Albis M A LANGOBARDI N Flevo Aue Alara IA Lacus DOLGUBNII L CANANEFATES ANGRIVARII I BATAVIFectio BatavodurumCHHAoMlsAtVeIrhausenAmisiaGERMA Visurgis CaCsHtEraR USScCeIlerata BERA CUVGeEtReNrIa LupiaHalternObBerRaUAdCneTrnEeRpIpen NIA SEMNONES Asciburgium USIPETES Rura MARSI Hedemünden Novaesium Sala Atuataca Ara Ubiorum UBII Bonna TENCTERI Rhenus Confluentes WaldgirmesDorlaCrHATTI HERMUNDURI Laugona Rödgen Arduenna MATTIACI Silva Mogontiacum GAL Mosella AugusTtRaE VTEreRIvorum Moënus L I Marktbreit A Civitas Nemetum B E L MARCOMANNI G I C A Argentorate Danuvius Augusta Vindelicorum Dangstetten RAETIA Vindonissa GALLIA LUGDUNENSIS Roman fort N Roman Empire Roman allies FRISII Tribes allied to Rome 0 100 miles MARSITribes not allied to Rome 0 100km ITALIA 9 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com The Opposing Sides RECRUITMENT AND MOTIVATION German Germanic and Roman societies both highly valued the warrior ethos. Though there were stark differences between these ancient cultures, there were also striking similarities. War fighting was a defining characteristic of most Germanic cultures. Demonstrating an aptitude for combat was a rite of passage for a boy. When he came of age, a young man was formally presented with his own lance and shield in the presence of his tribal assembly, a ritual regarded as the youth’s admission to the public life of his community. In wartime, 100 of the ablest young men were selected from the nation’s villages to accompany the cavalry on foot. Those able to run fast formed the vanguard of the attack because they were able to keep pace with the men on horseback. A select few, having proved their courage and skill, might then become retainers or companions of the clan or war chief. The Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus observes, there is an eager rivalry between the retainers for the post of honour next to their chief, as well as between different chiefs for the honour of having the most numerous and most valiant bodyguard. Here lie dignity and strength. To be perpetually surrounded by a large train of picked young warriors is a distinction in peace and a protection in war. (Tacitus, Germania 13) As well as for the honour of serving the highest status man in the community, a warrior also fought for the prestige of his family. In battle the Germanic soldier formed up next to his kith and kin – son, brother, father and uncle, all stood side by side. Their lives depended on the men next to them, each looking out 10 ©OspreyPublishing•www.ospreypublishing.com