POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945 PDF

Preview POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945

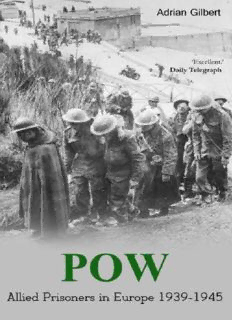

Pow Allied prisoners in Europe 1939–1945 Adrian Gilbert All Rights Reserved This edition published in 2014 by: Thistle Publishing 36 Great Smith Street London SW1P 3BU www.thistlepublishing.co.uk To Louis, and to Rosie and Freya Adrian Gilbert Adrian Gilbert has written extensively on military history. Among his books are World War One in Photographs; Britain Invaded, an imaginary account of a cross-channel German invasion in 1940; The Imperial War Museum Book of the Desert War, featuring firsthand accounts from British and Commonwealth forces in North Africa, 1940–42; and Sniper: One-on-One, a history of sharpshooting and sniping. Contents Illustrations Preface Maps 1. Battlefield Surrender 2. Capture from Air and Sea 3. The Road to the Camps 4. Camps and Captors 5. The Fabric of Daily Life 6. Leadership and Discipline 7. Forced Labour 8. 'Time on My Hands': Leisure, Entertainment and the Arts 9. The Written Word: Internal Escape and Self-Improvement 10. Other Nationalities 11. Medical and Spiritual Matters 12. Resistance, Punishment and Collaboration 13. Escape from Germany 14. An Italian Adventure 15. Migration and Liberation 16. Homecoming Postscript Notes Bibliography Illustrations Section One 1. Wounded Canadian soldiers at Dieppe 2. Delmar T. Spivey, SAO of Center compound, Stalag Luft III 3. Jim Witte in PG 78 at Sulmona 4. Revd Bob McDowall in New Zealand, 1940 5. Jack Vietor – a sketch by a fellow POW in Stalag Luft I 6. Bob Prouse shortly after joining up in Canada 7. Jimmy James on his return to England 8. Doug LeFevre on the run in northern Italy 9. Oflag IXA/H at Spangenberg 10. A German guard surveys Stalag Luft III 11. Stalag IVB at Mühlberg 12. A victim of the German shackling order 13. Wash day at a British POW work camp 14. Latrine contents are pumped into a 'honey wagon' 15. American air-force officers at Stalag Luft I 16. Two Indian POWs of a work detachment 17. A Sikh lieutenant of the Free Indian Legion Section Two 18. British POWs in a work-camp quarry, Stalag VIIIB 19. An imaginary radio show, Stalag Luft III 20. The cast of the 1940 Christmas panto, Oflag VIIC 21. An accordion–guitar band from a British Stalag 22. A Christmas card of Oflag VIIB 23. A scene from a POW production of Hamlet 24. The forged Ausweis of Billie Stephens 25. A British POW redraws a map of Germany 26. The Great Escape 'Harry' tunnel 27. Wing Commander H. M. A. 'Wings' Day 28. The prisoners' courtyard in Oflag IVC, Colditz 29. A convoy of Red Cross trucks en route to Germany 30. British POWs open Red Cross parcels 31. The contents of an American Red Cross parcel 32. A representative from the Swiss Protecting Power 33. Allied POWs cheer their liberation 34. Emaciated POWs from Fallingbostel Photographic credits: I, Sipho; 2, US Air Force Academy McDermott Library; 3, J. H. Witte; 4, 11, Mary Tagg; 5, Marc and Francesca Vietor; 6, Linda and Rob Prouse; 7, B. A. James; 8, Mrs LeFevre; 9, 10, 16, 18, 19, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 34, Imperial War Museum; 12, 14, 27, H. C. M. Jarvis; 13, 15, 21, 30, Museum & Archive, British Red Cross Society; 17, author's collection; 20, C. Whitcombe; 22, 23, Jonathan Goodliffe; 24, W. Stephens; 31 American Red Cross; 33, PNA. Preface A PPROXIMATELY 295,000 BRITISH and American servicemen were captured by the Axis forces of Germany and Italy during the Second World War. A precise number for British, Commonwealth and Empire POWs in Europe seems impossible to obtain; estimates for the three armed forces and the merchant marine range from 170,000 to 200,000 men, although the higher figure seems most likely. POW figures for the United States are more certain, however: around 95,000 soldiers and airmen were imprisoned by the Axis. Whereas most American prisoners were captured relatively late in the war – the majority entering captivity in 1944 – the British suffered several major defeats in the first half of the conflict, with the bulk of their prisoners being captured between 1940 and 1942. Consequently, the British were the long-stay detainees who tended to set the tone of the Anglo-American POW experience. British and American prisoners enjoyed a special status within the prison camps of Germany and Italy. Their homelands had not been overrun by the Axis – unlike those of many other Allied prisoners – and, as the war progressed, Britain and the United States accumulated ever-increasing numbers of enemy prisoners; the Germans and Italians were aware that the fate of their own men in captivity was largely dependent on the care of the British and American prisoners under their control. But if the treatment of British and American prisoners was better than that experienced by other POWs, captivity was still a wretched business. The gung- ho escape narratives that came to define prison life in the post-war years give a false gloss to the drab realities of existence behind barbed wire: poor living conditions, chronic – sometimes acute – hunger, deadening monotony, and the misery of being beholden to the will of the enemy with no release date in sight. Despite the fundamentally negative nature of POW life, there were positive aspects that sprang from the prisoners' own determination to make the most of

Description: