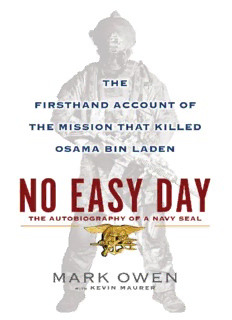

No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission That Killed Osama Bin Laden PDF

Preview No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission That Killed Osama Bin Laden

DUTTON Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.); Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England; Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd); Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd); Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India; Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd); Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Published by Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © 2012 by Mark Owen All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions. REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA has been applied for. ISBN 978-0-525-95372-2 eBook ISBN 978-1-101-61130-2 Designed by Spring Hoteling Photographs are from the author’s collection. Maps by Travis Rightmeyer The publisher acknowledges that the name Mark Owen is a pseudonym. While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. The only easy day was yesterday. —Navy SEAL Philosophy Long live the Brotherhood. CONTENTS TITLE PAGE COPYRIGHT AUTHOR’S NOTE PROLOGUE: Chalk One CHAPTER 1: Green Team CHAPTER 2: Top Five/Bottom Five CHAPTER 3: The Second Deck CHAPTER 4: Delta CHAPTER 5: Point Man CHAPTER 6: Maersk Alabama CHAPTER 7: The Long War CHAPTER 8: Goat Trails CHAPTER 9: Something Special in D.C. CHAPTER 10: The Pacer CHAPTER 11: Killing Time CHAPTER 12: Go Day CHAPTER 13: Infil CHAPTER 14: Khalid CHAPTER 15: Third Deck CHAPTER 16: Geronimo CHAPTER 17: Exfil CHAPTER 18: Confirmation CHAPTER 19: Touch the Magic EPILOGUE CONFIRMING SOURCES ABOUT THE AUTHORS PHOTO INSERT AUTHOR’S NOTE When I was in junior high school in Alaska, we were assigned a book report. We had to pick a book we liked. Moving down the row of books, I stumbled upon Men in Green Faces by former SEAL Gene Wentz. The novel chronicled missions in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Full of ambushes and firefights, it centered on the hunt for a rogue North Vietnamese colonel. From page one, I knew I wanted to be a SEAL. The more I read, the more I wanted to see if I could measure up. In the surf of the Pacific Ocean during training, I found other men just like me: men who feared failure and were driven to be the best. I was privileged to serve with and be inspired by these men every day. Working alongside them made me a better person. After thirteen consecutive combat deployments, my war is over. This book is closure for that part of my life. Before leaving, I wanted to try and explain what it was that motivated us through the brutal SEAL training course and through a decade of constant deployments. We are not superheroes, but we all share a common bond in serving something greater than ourselves. It is a brotherhood that ties us together, and that bond is what allows us to willingly walk into harm’s way together. This is the story of a group of extraordinary men who I was lucky enough to serve alongside as a SEAL from 1998 to 2012. I’ve changed the names of all the characters, including myself, to protect our identities, and this book does not include details of any ongoing missions. I’ve also taken great pains to protect the tactics, techniques, and procedures used by the teams as they wage a daily battle against terrorists and insurgents around the world. If you are looking for secrets, this is not your book. Although I am writing this book in an effort to accurately describe real-world events as they occurred, it is important to me that no classified information is released. With the assistance of my publisher, I hired a former Special Operations attorney to review the manuscript to ensure that it was free from mention of forbidden topics and that it cannot be used by sophisticated enemies as a source of sensitive information to compromise or harm the United States. I am confident that the team that has worked with me on this book has both maintained and promoted the security interests of the United States. When I refer to other military or government organizations, activities, or agencies, I do so in the interest of continuity and normally only if another publication or official unclassified government document has already mentioned that organization’s participation in the mission I’m describing. I sometimes refer to certain publicly recognized senior military leaders by their true names, only when it is clear that there are no operational security issues involved. In all other cases, I have intentionally depersonalized the stories to maintain the anonymity of the individuals involved. I do not describe any technologies that would compromise the security of the United States. All of the material contained within this book is derived from unclassified publications and sources; nothing written here is intended to confirm or deny, officially or unofficially, any events described or the activities of any individual, government, or agency. In an effort to protect the nature of specific operations, I sometimes generalize dates, times, and order of events. None of these “work-arounds” affect the accuracy of my recollections or my description of how events unfolded. The operations discussed in this book have been written about in numerous other civilian and government publications and are available in open sources to the general public. These confirming open-source citations are printed in the Confirming Sources list at the end of this book. The events depicted in No Easy Day are based on my own memory. Conversations have been reconstructed from my recollections. War is chaotic, but I have done my best to ensure the stories in this book are accurate. If there are inaccuracies in it, the responsibility is mine. This book presents my views and does not represent the views of the United States Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or anyone else. In spite of the deliberate measures I have undertaken to protect the national security of the United States and the operational security of the men and women who continue to fight around the world, I believe No Easy Day to be an accurate portrayal of the events it describes and an honest portrayal of life in the SEAL teams and the brotherhood that exists among us. While written in the first person, my experiences are universal, and I’m no better or worse than any man I’ve served with. It was a long, hard decision to write this book, and some in the community will look down on me for doing so. However, it is time to set the record straight about one of the most important missions in U.S. military history. Lost in the media coverage of the Bin Laden raid is why and how the mission was successful. This book will finally give credit to those who earned it. The mission was a team effort, from the intelligence analysts who found Osama bin Laden to the helicopter pilots who flew us to Abbottabad to the men who assaulted the compound. No one man or woman was more important than another. No Easy Day is the story of “the guys,” the human toll we pay, and the sacrifices we make to do this dirty job. This book is about a brotherhood that existed long before I joined and will be around long after I am gone. My hope is one day a young man in junior high school will read it and become a SEAL, or at least live a life bigger than him. If that happens, the book is a success. Mark Owen June 22, 2012, Virginia Beach, Virginia PROLOGUE Chalk One At one minute out, the Black Hawk crew chief slid the door open. I could just make him out—his night vision goggles covering his eyes—holding up one finger. I glanced around and saw my SEAL teammates calmly passing the sign throughout the helicopter. The roar of the engine filled the cabin, and it was now impossible to hear anything other than the Black Hawk’s rotors beating the air. The wind buffeted me as I leaned out, scanning the ground below, hoping to steal a glance of the city of Abbottabad. An hour and a half before, we’d boarded our two MH-60 Black Hawks and lifted off into a moonless night. It was only a short flight from our base in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, to the border with Pakistan, and from there another hour to the target we had been studying on satellite images for weeks. The cabin was pitch-black except for the lights from the cockpit. I had been wedged against the left door with no room to stretch out. We’d stripped the helicopter of its seats to save on weight, so we either sat on the floor or on small camp chairs purchased at a local sporting goods store before we left. Now perched on the edge of the cabin, I stretched my legs out the door trying to get the blood flowing. My legs were numb and cramped. Crowded into the cabin around me and in the second helicopter were twenty-three of my teammates from the Naval Special Warfare Development Group, or DEVGRU. I had operated with these men dozens of times before. Some I had known ten years or more. I trusted each one completely. Five minutes ago, the whole cabin had come alive. We pulled on our helmets and checked our radios and then made one final check of our weapons. I was wearing sixty pounds of gear, each gram meticulously chosen for a specific purpose, my load refined and calibrated over a dozen years and hundreds of similar missions. This team had been handpicked, assembled of the most experienced men in our squadron. Over the last forty-eight hours, as go day loomed and then was postponed and then loomed again, we had each checked and rechecked our equipment so we were more than ready for this night. This was a mission I’d dreamt about since I watched the September 11, 2001, attacks on a TV in my barracks room in Okinawa. I was just back from training and got into my room in time to see the second plane crash into the World Trade Center. I couldn’t turn away as the fireball shot out of the opposite side of the building and smoke billowed out of the tower. Like millions of Americans back home, I stood there watching in disbelief with a hopeless feeling in the pit of my stomach. I stayed transfixed to the screen for the rest of the day as my mind tried to make sense of what I’d just witnessed. One plane crash could be an accident. The unfolding news coverage confirmed what I had known the moment the second plane entered the TV shot. A second plane was an attack, no doubt. No way that happened by accident. On September 11, 2001, I was on my first deployment as a SEAL, and as Osama bin Laden’s name was mentioned I figured my unit would get the call to go to Afghanistan the next day. For the previous year and a half, we’d been training to deploy. We’d trained in Thailand, the Philippines, East Timor, and Australia over the last few months. As I watched the attacks, I longed to be out of Okinawa and in the mountains of Afghanistan, chasing al Qaeda fighters and serving up a little payback. We never got the call. I was frustrated. I hadn’t trained so hard and for so long to become a SEAL only to watch the war on TV. Of course, I wasn’t about to let my family and friends in on my frustration. They were writing asking me if I was going to Afghanistan. To them, I was a SEAL and it was only logical that we would be immediately deployed to Afghanistan. I remember that I sent an e-mail to my girlfriend at the time trying to make light of a bad situation. We were talking about the end of this deployment and making plans for my time at home before the next deployment. “I’ve got about a month left,” I wrote. “I’ll be home soon, unless I have to kill Bin Laden first.” It was the kind of joke you heard a lot back then. Now, as the Black Hawks flew toward our target, I thought back over the last ten years. Ever since the attacks, everyone in my line of work had dreamt of being involved in a mission like this. The al Qaeda leader personified everything we were fighting against. He’d inspired men to fly planes into buildings filled with innocent civilians. That kind of fanaticism is scary, and as I watched the towers crumble and saw reports of attacks in Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, I knew we were at war, and not a war of our choosing. A lot of brave men had sacrificed for years to fight the war, never knowing if we would get a chance to be involved in a mission like the one about to begin. A decade after that event and with eight years of chasing and killing al Qaeda’s leaders, we were minutes away from fast-roping into Bin Laden’s compound. Grabbing the rope attached to the Black Hawk’s fuselage, I could feel the blood finally returning to my toes. The sniper next to me slid into place with one leg hanging outside and one leg inside the helicopter so that there was more room in the already-tight doorway. The barrel of his weapon was scanning for targets in the compound. His job was to cover the south side of the compound as the assault team fast-roped into the courtyard and split up to our assignments. Just over a day ago, none of us had believed Washington would approve the mission. But after weeks of waiting, we were now less than a minute from the compound. The intelligence said our target would be there; I figured he was, but nothing would surprise me. We’d thought we were close a couple times before. I had spent a week in 2007 chasing rumors of Bin Laden. We had received reports that he was coming back into Afghanistan from Pakistan for a final stand. A source said he’d seen a man in “flowing white robes” in the mountains. After weeks of prep, it was ultimately a wild-goose chase. This time felt different. Before we left, the CIA analyst who was the main force behind tracking the target to Abbottabad said she was one hundred percent certain he was there. I hoped she was right, but my experience told me to reserve judgment until the mission was over. It didn’t matter now. We were seconds away from the house and whoever was living in there was about to have a bad night. We had completed similar assaults countless times before. For the last ten years, I had deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, and to the Horn of Africa. We had been part of the mission to rescue Richard Phillips, the captain of the container ship Maersk Alabama, from three Somali pirates in 2009, and I had operated in Pakistan before. Tactically, tonight was no different from a hundred other operations; historically, I hoped it was going to be very different. As soon as I gripped the rope, a calm came over me. Everyone on the mission had heard that one-minute call a thousand times before and at this point it was no different than any other operation. From the door of the helicopter, I started to make out landmarks I recognized from studying satellite images of the area during our weeks of training. I wasn’t clipped into the helicopter with a safety line, so my teammate Walt had a hand on a nylon loop on the back of my body armor. Everybody was crowding toward the door right behind me ready to follow me down. On the right side, my teammates had a good visual of the trail helicopter with Chalk Two heading to its landing zone. As soon as we cleared the southeastern wall, our helicopter flared out and started to hover near our predetermined insert point. Looking down thirty feet into the compound, I could see laundry whipping on a clothesline. Rugs hung out to dry were battered by dust and dirt from the rotors. Trash swirled around the yard, and in a nearby animal pen, goats and cows thrashed around, startled by the helicopter. Focused on the ground, I could see we were still over the guesthouse. As the helicopter rocked, I could tell the pilot was having some trouble getting the aircraft into position. We veered between the roof of the guesthouse and the wall of the compound. Glancing over at the crew chief, I could see he had his radio microphone pressed against his mouth, passing directions to the pilot. The helicopter was bucking as it tried to find enough air to set a stable hover and hold station. The wobbling wasn’t violent, but I could tell it wasn’t planned. The pilot was fighting the controls trying to correct it. Something wasn’t right. The pilots had done this kind of mission so many times that for them putting a helicopter over a target was like parking a car. Staring into the compound, I considered throwing the rope just so we could get out of the unstable bird. I knew it was a risk, but getting on the ground was imperative. There wasn’t anything I could do stuck in the door of the helicopter. All I needed was a clear spot to throw the rope. But the clear spot never came. “We’re going around. We’re going around,” I heard over the radio. That meant the original plan to fast-rope into the compound was now off. We were going to circle around to the south, land, and assault from outside the wall. It would add precious time to the assault and allow anyone inside the compound more time to arm themselves. My heart sank. Up until I heard the go-around call, everything was going as planned. We had evaded the Pakistani radar and anti-aircraft missiles on the way in and arrived undetected. Now, the insert was already going to shit. We had rehearsed this contingency, but it was plan B. If our target was really inside, surprise was the key and it was quickly slipping away. As the helicopter attempted to climb out of its unstable hover, it took a violent right turn, spinning ninety degrees. I could feel the tail kick to the left. It caught me by surprise and I immediately struggled to find a handhold inside the cabin to keep from sliding out the door. I could feel my butt coming off the floor, and for a second I could feel a panic rising in my chest. I let go of the rope and started to lean back into the cabin, but my teammates were all crowded in the door. There was little room for me to scoot back. I could feel Walt’s grip tighten on my body armor as the helicopter started to drop. Walt’s other hand held the sniper’s gear. I leaned back as far as I could. Walt was practically lying on top of me to keep me inside. “Holy fuck, we’re going in,” I thought. The violent turn put my door in the front as the helicopter started to slide sideways. I could see the wall of the courtyard coming up at us. Overhead, the engines, which had been humming, now seemed to scream as they tried to beat the air into submission to stay aloft. The tail rotor had barely missed hitting the guesthouse as the helicopter slid to the left. We had joked before the mission that our helicopter had the lowest chance of crashing because so many of us had already survived previous helicopter crashes. We’d been sure if a helicopter was going to crash it would be the one carrying Chalk Two. Thousands of man-hours, maybe even millions, had been spent leading the United States to this moment, and the mission was about to go way off track before we even had a chance to get our feet on the ground. I tried to kick my legs up and wiggle deeper into the cabin. If the helicopter hit on its side, it might roll, trapping my legs under the fuselage. Leaning back as far as I could, I pulled my legs into my chest. Next to me, the sniper tried to clear his legs from the door, but it was too crowded. There was nothing we could do but hope the helicopter didn’t roll and chop off his exposed leg. Everything slowed down. I tried to push the thoughts of being crushed out of my mind. With every second, the ground got closer and closer. I felt my whole body tense up, ready for the inevitable impact. CHAPTER 1 Green Team I could feel the sweat dripping down my back, soaking my shirt, as I slowly moved down the corridor of the kill house at our training site in Mississippi. It was 2004, seven years before I would ride a Black Hawk into Abbottabad, Pakistan, on one of the most historic special operations raids in history. I was in the selection and training course for SEAL Team Six, sometimes called by its full name: United States Naval Special Warfare Development Group, abbreviated DEVGRU. The nine-month selection course was known as Green Team, and it was the one thing that stood between me and the other candidates moving up to the elite DEVGRU. My heart was beating fast, and I had to blink the perspiration out of my eyes as I followed my teammate to the door. My breathing was labored and ragged as I tried to force any extraneous thoughts from my head. I was nervous and edgy, and that was how mistakes were made. I needed to focus, but no matter what was in the room we were about to enter, it paled compared to the cadre of instructors watching on the catwalk. All of the instructors were senior combat veterans from DEVGRU. Handpicked to train new operators, they held my future in their hands. “Just get to lunch,” I muttered to myself. It was the only way I could control my anxiety. In 1998, I’d made it through Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL, or BUD/S, by focusing on just making it to the next meal. It didn’t matter if I couldn’t feel my arms as we hoisted logs over our heads or if the cold surf soaked me to the core. It wasn’t going to last forever. There is a saying: “How do you eat an elephant?” The answer is simple: “One bite at a time.” Only my bites were separated by meals: Make it to breakfast, train hard until lunch, and focus until dinner. Repeat. In 2004, I was already a SEAL, but making it to DEVGRU would be the pinnacle of my career. As the Navy’s counter-terrorism unit, DEVGRU did hostage rescue missions, tracked war criminals, and, since the attacks on September 11, hunted and killed al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan and Iraq. But nothing about making it through Green Team was easy. It was no longer good enough for me to be a SEAL. During Green Team, just passing was failing and second place was the first loser. The point was not to meet the minimums, but crush them. Success in Green Team was about managing stress and performing at your peak level—all the time. Before each training day, we completed a punishing physical training or PT workout of long runs, push-ups, pull-ups, and anything else the sadistic instructors could cook up. We pushed cars, and on multiple occasions we pushed buses. When we got to the kill house, a purpose-built ballistically safe building made up of hallways and rooms used to practice close-quarters battle, or CQB, our muscles were already tired and sore. The point of doing the PT was to make us physically tired to simulate the stress of a real mission before they tested us in a demanding tactical environment. I didn’t have time to steal a glimpse at the instructors as we moved down the hall. This was the first day of training, and everybody’s nerves were running high. We had started CQB training after completing a full month’s worth of high-altitude parachute training in Arizona. The pressure to perform had been evident there too, but once we got to Mississippi it was ratcheted up. I shook the nagging aches and pains from my mind and concentrated on the door in front of me. It was made of thin plywood with no doorknob. The door was battered and broken from teams that went before us, and my teammate easily pushed it open with his gloved hand. We paused for a second at the threshold, scanning for targets before we entered. The room was square, with rough walls made of old railroad ties to absorb the live rounds. I could hear my teammate enter behind me as I swept my rifle in an arc searching for a target. Nothing. The room was empty. “Moving,” my teammate called as he stepped into the room to clear around a corner. Instinctually, I slid into position to cover him. As soon as I started to move, I could hear murmuring above me in the rafters. We couldn’t stop, but I knew one of us had just made a mistake. For a second, my stress level spiked, but I quickly pushed it out of my mind. There was no time to worry about mistakes. There were more rooms to clear. I couldn’t worry about the mistakes I made in the first room. Back in the hall, we entered the next room. I spotted two targets as I entered. To the right, I saw the silhouette of a crook holding a small revolver. He was wearing a sweatshirt and looked like a 1970s thug from the movies. To the left, there was a silhouette of a woman holding a purse. I snapped a shot off at the crook seconds after stepping into the room. The round hit center mass. I moved toward it, shooting a few more rounds. “Clear,” I said, lowering my muzzle. “Clear,” my teammate answered. “Safe ’em and let ’em hang,” one of the instructors said from above. No less than six instructors were looking down at us from a catwalk that spidered out over the kill house. They could walk safely along the walkways watching as we cleared the different rooms, judging our performance and watching for any tiny mistakes. I put my rifle on safe and let it hang against me by its sling. I wiped beads of sweat out of my eyes with my sleeve. My heart was still pounding, even though we were finished. The training scenarios were pretty straightforward. We all knew how to clear rooms. It was the process of clearing a room perfectly under the simulated stress of combat that would set us apart. There was no margin of error, and at that moment I wasn’t sure exactly what we had done wrong. “Where was your move call?” Tom, one of the instructors, said to me from the catwalk. I didn’t answer. I just nodded. I was embarrassed and disappointed. I’d forgotten to tell my teammate to move in the first room, which was a safety violation. Tom was one of the best instructors in the course. I could always pick him out because he had a huge head. It was massive, like it housed a giant brain. It was his one distinct physical trait; otherwise you’d miss him because he was mellow and never seemed to get upset. We all respected him because he was both firm and fair. When you made a mistake in front of Tom, it felt like you let him down. His disappointment with me was plastered across his face. No screaming. No yelling. Just the look. From above, I saw him shoot me the “Dude, really? Did you just do that?” look. I wanted to speak or at least try and explain, but I knew they didn’t want to hear it. If they said you were wrong, you were wrong. Standing below them in the empty room, there was no arguing or explaining. “OK, check,” I said, defenseless and furious with myself for making such a basic error. “We need better than that,” Tom said. “Beat it. Do your ladder climb.” Snatching up my rifle, I jogged out of the kill house and sprinted to a rope ladder hanging on a tree about three hundred yards away. Climbing up the ladder, rung by rung, I felt heavier. It wasn’t my sweat-soaked shirt or the sixty pounds of body armor and gear strapped to my chest. It was my fear of failure. I’ve never failed anything in my SEAL career. When I got to San Diego six years earlier for BUD/S, I never doubted I’d make it. A lot of my fellow BUD/S candidates who arrived with me either got cut or quit. Some of them couldn’t keep up with the brutal beach runs, or they panicked underwater during SCUBA training. Like a lot of other BUD/S candidates, I knew I wanted to become a SEAL when I was thirteen. I read every book I could find about the SEALs, followed the news during Desert Storm for any mention of them, and daydreamed about ambushes and coming up over the beach on a combat mission. I wanted to do all of the things I’d read in the books while growing up. After completing my degree at a small college in California, I went to BUD/S and earned my SEAL trident in 1998. After a six-month deployment throughout the Pacific Rim, and a combat deployment to Iraq in 2003–2004, I was ready for something new. I’d learned about DEVGRU during my first two deployments. DEVGRU was a collection of the best the SEAL community had to offer, and I knew I would never be able to live with myself if I didn’t try. The Navy’s counter-terrorism unit was born in the aftermath of Operation Eagle Claw, the failed 1980 mission ordered by President Jimmy Carter to rescue fifty-two Americans held captive at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran. After the mission, the Navy identified a need for a force capable of successfully executing those kind of specialized missions and tapped Richard Marcinko to develop a maritime counter-terrorism unit called SEAL Team Six. The team practiced hostage rescue as well as infiltrating enemy countries, ships, naval bases, and oil rigs. Over time, missions branched out to counter-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. At the time Marcinko established the command, there were only two SEAL teams, so “six” was chosen to make the Soviets think the Navy had more teams. In 1987, SEAL Team Six became DEVGRU. The unit started with seventy-five operators, handpicked by Marcinko. Now, all of the members of the unit are handpicked from other SEAL teams and Explosive Ordnance Disposal units. The unit has grown significantly and filled out with numerous teams of operators as well as support staff, but the concept remains the same. The unit is part of the Joint Special Operations Command, called JSOC. DEVGRU works closely with other National Missions Force teams like the Army’s Delta Force. One of DEVGRU’s first missions was in 1983 during Operation Urgent Fury. Members of the unit rescued Grenada’s governor-general, Paul Scoon, during the U.S.–led invasion of the small Caribbean nation after a Communist takeover. Scoon was facing execution. Six years later in 1989, DEVGRU joined with Delta Force to capture Manuel Noriega during the invasion of Panama. DEVGRU operators were part of the U.S.–led mission to capture Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid in October 1993, which turned into the Battle of Mogadishu. The fight was chronicled in Mark Bowden’s book Black Hawk Down. In 1998, DEVGRU operators tracked Bosnian war criminals, including Radislav Krstic, the Bosnian general who was later indicted for his role in the Srebrenica massacre of 1995. Since September 11, 2001, DEVGRU operators had been on a steady cycle of deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, targeting al Qaeda and Taliban commanders. The command got the immediate call to insert into Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, and operators in the command were responsible for some of the high-profile missions like the Jessica Lynch rescue in Iraq in 2003. It was missions like these and the fact that they are the first to get the call that motivated me. Before you can screen for Green Team, you need to be a SEAL, and most candidates typically have two deployments. The deployments usually mean the candidate has the necessary skill level and experience, which was needed to complete the selection course. As I climbed the rungs on the ladder in the Mississippi heat, I couldn’t help but think about how I’d almost failed the three-day screening process before even starting Green Team. The dates for the screening fell during my unit’s land warfare training. I was at Camp Pendleton, California, hiding under a tree, watching Marines build a base camp. It was 2003 and we were a week into our reconnaissance training block when I got orders to report back to San Diego to start the three-day screening process. If I was lucky enough to get selected, I would begin the nine-month Green Team training course. If I was lucky enough to pass, I would join the ranks of DEVGRU. I was the only one in my platoon going. A buddy in a sister platoon was also screening. As we drove down together, we both were washing the green paint off our faces. Still dressed in our camouflage uniforms, we smelled of body odor and bug spray after spending days in the field. My stomach hurt from eating nothing but Meals, Ready-To-Eat, and I tried to hydrate, sucking down water as we drove. I was not in the best physical shape, and I knew the first part of the screening was a fitness test. The next morning, we were out at the beach. The sun was just peeking over the horizon as I finished the four-mile timed run. After a short break, I joined about two dozen other candidates in a line on a concrete pad. A breeze blew off the Pacific, and there was a little chill in the air from the

Description: