Native North American armor, shields, and fortifications PDF

Preview Native North American armor, shields, and fortifications

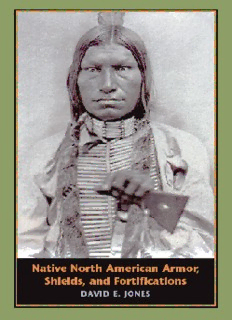

00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page i Native North American Armor, Shields, and Fortifications G&S Typesetters PDF proof THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40AM Pageiii Native North American Armor, Shields, and Fortifications by David E. Jones University of Texas Press, Austin G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page iv Copyright © 2004 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2004 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819. (cid:1)(cid:2) The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, David E., 1942– Native North American armor, shields, and fortifications / by David E. Jones. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN0-292-70209-4 (cl.: alk. paper) ISBN0-292-70170-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Warfare. 2. Indian weapons—North America. 3. Indian armor—North America. 4. Fortification—North America. I. Title. E98.W2J66 2004 623.4(cid:1)41—dc21 2003007786 G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page v Contents Acknowledgments vi Introduction vii Chapter 1 People of the RiversThe Prairie Culture Area 1 Chapter 2 Standing Fights and Poison Arrows The California Culture Area 14 Chapter 3 The Horse WarriorsThe High Plains Culture Area 27 Chapter 4 The Castle BuildersThe Northeast Culture Area 47 Chapter 5 The Importance of Influential Neighbors The Plateau/Basin Culture Area 64 Chapter 6 Warriors with Glittering ShieldsThe Southwest Culture Area 73 Chapter 7 Land of the Cold Snow ForestsThe Subarctic Culture Area 88 Chapter 8 The Salmon KingsThe Northwest Coast Culture Area 95 Chapter 9 The StrongbowsThe Southeast Culture Area 118 Chapter 10 Home of the North WindThe North Pacific Culture Area 145 Conclusion 159 Bibliography 165 Index 183 G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page vi Acknowledgments I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my wife, Jane Morris Jones, for en- couragement, emotional and intellectual support, and invaluable edi- torial assistance. I am also grateful to Gil Gillespie for artwork, and to Dr. Michael G. Davis and Dr. Wayne Van Horne for reading an early draft of this manuscript and making crucial suggestions. Of course, the final re- sponsibility for any statement made in this work is mine. vi G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page vii Introduction The nature of North American Indian cultures at the time of European contact in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is poorly understood. Eu- ropeans who first entered the New World were, for the most part, un- trained in scientific observation. In addition, depopulation from intro- duced diseases caused rapid changes in traditional Indian lifeways. This drastic reduction in populations forced abandonment of ancient home- lands; emptying of towns; and devastating economic, religious, and po- litical restructuring. Warfare against superior numbers of Europeans and advanced military technology shattered the societies that remained. One fact, however, stands strikingly clear: At the time of contact, war- fare was endemic among the North American Indians. (See Holm 1996 for further discussion and sources concerning early Indian warfare.) Her- nando De Soto, one of the first to traverse Indian country in the South- east, found rabid hostilities among neighboring groups. His chroniclers described a semiprofessional warrior caste and fortified villages. Later trav- elers reported the grouping of Indians into chiefdoms and large confed- eracies, both to better defend themselves and to aggress against others. The Chickasaw fought the Choctaw, the Creeks fought with the Cherokee, the Calusa battled with Timucuans, and at the time of contact, all north- ern Florida Indians hated the Apalachee. In the Southwest the Apaches fought the tribes of the Pueblos. On the Plains the Blackfeet fought the Crow, the Sioux fought the Cheyenne, and the Crow fought the Sho- shone. Explorers like Henry Hudson in New York, Samuel de Champlain in Canada, and George Vancouver on the Northwest Coast reported a sim- ilar situation in terms of Indian relationships. The early accounts of In- dian culture also depicted sophisticated offensive and defensive martial technology. The most complex, and to most contemporary Americans probably the most surprising, was the presence of armor among almost all Indian groups. Given the significance of armoring in warfare and the obvious ubiquity of warfare in native American culture at the time of contact, one would vii G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40AM Pageviii NATIVE NORTH AMERICAN ARMOR, SHIELDS, AND FORTIFICATIONS think that historians and ethnologists would have dealt with the subject exhaustively. However, in perusing the past several years of American An- tiquity,I found no archaeologically related references to armor, and in sur- veying forty thousand citations in The Ethnographic Bibliography of North America, I encountered the word “armor” only once, in Hough’s “Primi- tive American Armor,” published in 1895 in the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Hough’s report simply described the specimens of native American armor housed in the United States Na- tional Museum; no systematic survey of the topic was attempted. Frank R. Secoy (1953), in his classic Changing Military Patterns of the Great Plains In- dians,devoted a handful of pages to Indian armor but, again, drew most of his references from the Hough article. This pattern of dependence on the Hough piece has been repeated in a number of scanty references to ar- mor found in various “dictionaries” and casual accounts of American In- dian lore and material culture. Because a wide-ranging study of North American Indian defensive tech- nology—armor, shields, fortifications—is lacking, this work will seek to fill that void with a systematic survey from the Southeast to the Northwest Coast, from the Northeast Woodlands to the desert Southwest, and from the Subarctic to the Great Plains. I will provide a preliminary step toward a broader ethnological investigation of the relationship among warfare, defensive technology, and the evolution of political entities. Likewise, the focus of this work will assist the understanding of the relationship of sub- sistence base to defensive technology, as well as to many other ethnolog- ical, historical, and ethnohistorical issues related to warfare. Many questions that rely on a basic survey of information arise. What are possible diffusion routes of armor and general defensive technology coming into native North America from surrounding cultures? Did trade systems in which armor was a major commodity exist in North America? Is armor style related to subsistence activity? Under what conditions do shields evolve—change shape and size—and become mystical accoutre- ments of the warriors? It is to the service of such investigations that the material in this book is directed. For example, John Keegan (1994, 139–142), when discussing fortifica- tions in A History of Warfare, differentiates among refuges, strongholds, and strategic defenses and suggests that each form relates to a certain type of political environment. Refuges function as short-term defense and only work against an enemy without the means to linger in an area for long periods. Refuges simply have to deter an enemy from organizing an as- viii G&S Typesetters PDF proof 00-T2779-FM 10/22/03 11:40 AM Page ix INTRODUCTION sault. A stronghold, on the other hand, must be able to withstand attack- ers who can maintain supply lines to the siege site. Strongholds must be large enough to protect and house a garrison when under attack. They typically possess walls, towers, and some sort of moat—wet or dry. In the “strategic systems” type of fortification, multiple strongholds connect, much like a wall, to deny enemies access over a wide offensive front. Kee- gan concludes that refuges are most likely found in small-scale societies of the band or tribal type, whereas “Strongholds are a product of small or di- vided sovereignties; they proliferate when central authority has not been established or is struggling to secure itself or has broken down” (1994, 142). With regard to strategic defenses, he writes, “strategic defenses are the most expensive form of fortification to construct, to maintain and to garrison, and their existence is always a mark of the wealth and advanced political development of the people who build them” (1994, 142). The application of Keegan’s observations on fortification and political structure to the North American Indian scene depends, of course, on the presentation of sufficient information to be able to pursue his argument. This book seeks to fill this informational gap. Throughout this volume I will use the term “warfare” in a very general sense to mean fighting among members of a specific social group or be- tween two or more groups. A more refined rendering might consider “war- fare” to mean a state-level form of massed social aggression involved with maintaining and supplying an army in the field, with the ultimate aim of occupying an enemy’s territory, while “raids” can be described as military operations which, if successful, require only one strike. A “raid” might be seen as a message to a potential enemy to stop the behavior that is upset- ting the attacking group. A “feud” is more or less a family affair. Classi- cally, it is about the vengeance of kinsmen against those individuals who have assaulted the life or honor of the kin group. A “military demonstra- tion” is a show, a display engineered to impress the enemy with the futil- ity of further hostilities or to distract an enemy while the real strategy is being acted out. Most North American Indian warfare was of the raid and feud variety, although true warfare, in which one group maintained concerted pressure on another for the purposes of genocide or the removal of a people from their territory, existed. In some places at some times, war was unremitting, while in others lack of defensive arrangements or the dilapidation of for- mer stout palisades indicated a low level of hostilities. In some cases thou- sands of fighters were involved; much more often, however, the number ix G&S Typesetters PDF proof

Description: