Manhood: A Journey from Childhood into the Fierce Order of Virility PDF

Preview Manhood: A Journey from Childhood into the Fierce Order of Virility

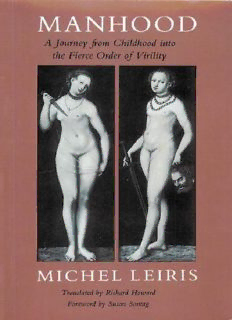

Manhood A JOURNEY FROM CHILDHOOD INTO THE FIERCE ORDER OF VIRILITY Michel Leiris TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY RICHARD HOWARD WITH A FOREWORD BY SUSAN SONTAG To Georges Bataille who is at the origin of this book The University of Chicago Press Translation copyright © 1963, 1984 by Richard Howard Translator's Note copyright © 1983 by Richard Howard Originally published in French under the title of L'Age d'homme, copyright © 1939, 1946 by Editions Gallimard Foreword is "Michel Leiris' Manhood" from Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag. Copyright © 1964, 1966 by Susan Sontag. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Leiris, Michel, 1901- (Age d'homme. English) Manhood : a journey from childhood into the fierce order of virility / Michel Leiris : translated from the French by Richard Howard, p. cm. Translation of : L'âge d'homme. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Leiris, Michel, 1901 Biography. 2. Poets, French— 20th century—Biography. 3. Anthropologists —France— Table Of Contents Foreword Translator's Note, 1983 PROLOGUE OLD AGE AND DEATH SUPERNATURE INFINITY THE SOUL SUBJECT AND OBJECT I Tragic Themes II Classical Themes WOMEN OF CLASSICAL TIMES HEROIC WOMEN SACRIFICES BROTHELS AND MUSEUMS THE GENIUS OF THE HEARTH DON JUAN AND THE COMMENDATORE III Lucrece MY UNCLE THE ACROBAT EYES PUT OUT PUNISHED GIRL MARTYRED SAINT IV Judith CARMEN LA GLU SALOME ELECTRA, DELILAH, AND FLORIA TOSCA THE FLYING DUTCHMAN NARCISSUS V The Head of Holofernes THROAT CUT PENIS INFLAMED HURT FOOT, BITTEN BUTTOCK, CUT HEAD NIGHTMARES MY BROTHER MY ENEMY MY BROTHER MY FRIEND STITCHES VI Lucrece and Judith VII The Loves of Holofernes KAY HOLOFERNES' FEAST VIII The Raft of the Medusa THE TURBAN-WOMAN THE BLEEDING NAVEL AFTERWORD The Autobiographer as Torero SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY The Author Foreword Arriving in translation in the year 1963, Michel Leiris's brilliant autobiographical narrative L'Age d'homme is at first rather puzzling. Manhood, as it is called in English, appears without any covering note. There is no way for the reader to find out that Leiris, now in his sixties{1} and the author of some twenty books, none of which are yet in English, is an important poet and senior survivor of the Surrealist generation in Paris in the 1920s, and a fairly eminent anthropologist. Nor does the American edition explain that Manhood is not recent—that it was in fact written in the early 1930s, first published in 1939, and republished with an important prefatory essay, "Literature Considered as a Bullfight" [published in this volume as an afterword: "The Autobiographer as Torero"], in 1946, when it had a great succès de scandale. Although autobiographies can enthrall even though we have no prior interest—or reason for becoming interested—in the writer, the fact that Leiris is unknown here complicates matters, because his book is very much part of a life history as well as a lifework. In 1929, Leiris suffered a severe mental crisis, which included becoming impotent, and underwent a year or so of psychiatric treatment. In 1930, when he was thirty-four years old, he began Manhood. At that time, he was a poet, strongly influenced by Apollinaire and by his friend Max Jacob; he had already published several volumes of poetry, the first of which is Simulacre (1925); and in the same year that he began Manhood, he wrote a remarkable novel in the Surrealist manner, Aurora. But shortly after beginning Manhood (it was not finished until 1935), Leiris entered upon a new career—as an anthropologist. He made a field trip to Africa (Dakar and Djibouti) in 1931-33, and upon his return to Paris joined the staff of the Musée de l'Homme, where he remains, in an important curatorial post, to the present day. No trace of this startling shift— from bohemian and poet to scholar and museum bureaucrat—is recorded in the wholly intimate disclosures of Manhood. There is nothing in the book of the accomplishments of the poet or the anthropologist. One feels there cannot be; to have recorded them would mar the impression of failure. Instead of a history of his life, Leiris gives us a catalogue of its limitations. Manhood begins not with "I was born in . . ." but with a matter-of-fact description of the author's body. We learn in the first pages of Leiris's incipient baldness, of a chronic inflammation of the eyelids, of his meager sexual capacities, of his tendency to hunch his shoulders when sitting and to scratch his anal region when he is alone, of a traumatic tonsillectomy undergone as a child, of an equally traumatic infection in his penis; and, subsequently, of his hypochondria, of his cowardice in all situations of the slightest danger, of his inability to speak any foreign language fluently, of his pitiful incompetence in physical sports. His character, too, is described under the aspect of limitation: Leiris presents it as "corroded" with morbid and aggressive fantasies concerning the flesh in general and women in particular. Manhood is a manual of abjection—anecdotes and fantasies and verbal associations and dreams set down in the tones of a man, partly anesthetized, curiously fingering his own wounds. One may think of Leiris's book as an especially powerful instance of the venerable preoccupation with sincerity peculiar to French letters. From Montaigne's Essays and Rousseau's Confessions through Stendhal's journals to the modern confessions of Gide, Jouhandeau, and Genet, the great writers of France have been concerned to a singular extent with the detached presentation of intimate feelings, particularly those connected with sexuality and ambition. In the name of sincerity, both in autobiographical form and in the form of fiction (as in Constant, Laclos, Proust), French writers have been coolly exploring erotic manias, and speculating on techniques of emotional disengagement. It is this long-standing preoccupation with sincerity—over and beyond emotional expressiveness—that gives a severity, a certain classicism even, to most French works of the romantic period. But to see Leiris's book simply in this way does it an injustice. Manhood is odder, harsher than such a lineage suggests. Far more than any avowals to be found in the great French autobiographical documents of incestuous feelings, sadism, homosexuality, masochism, and crass promiscuity, what Leiris admits to is obscene and repulsive. It is not especially what Leiris has done that shocks. Action is not his forte, and his vices are those of a fearfully cold sensual temperament—wormy failures and deficiencies more often than lurid acts. It is because Leiris's attitude is unredeemed by the slightest tinge of self-respect. This lack of esteem or respect for himself is obscene. All the other great confessional works of French letters proceed out of self-love, and have the clear purpose of defending and justifying the self. Leiris loathes himself, and can neither defend nor justify. Manhood is an exercise in shamelessness—a sequence of self-exposures of a craven, morbid, damaged temperament. It is not incidentally, in the course of his narration, that Leiris reveals what is disgusting about himself. What is disgusting is the topic of his book. One may well ask: who cares? Manhood undoubtedly has a certain value as a clinical document; it is full of lore for the professional student of mental aberration. But the book would not be worth attention did it not have value as literature. This, I think, it does—though, like so many modern works of literature, it makes its way as anti-literature. (Indeed, much of the modern movement in the arts presents itself as anti-art.) Paradoxically, it is just its animus to the idea of literature that makes Manhood—a very carefully (though not beautifully) written and subtly executed book—interesting as literature. In the same way, it is precisely through Manhooďs unstated rejection of the rationalist project of self-understanding that Leiris makes his contribution to it. The question that Leiris answers in Manhood is not an intellectual one. It is what we would call a psychological—and the French, a moral—question. Leiris is not trying to understand himself. Neither has he written Manhood to be forgiven, or to be loved. Leiris writes to appall, and thereby to receive from his readers the gift of a strong emotion—the emotion needed to defend himself against the indignation and disgust he expects to arouse in his readers. Literature becomes a mode of psychotechnics. As he explains in the prefatory essay "De la litérature considérée comme une tauromachie," to be a writer, a man of letters, is not enough. It is boring, pallid. It lacks danger. Leiris must feel, as he writes, the equivalent of the bullfighter's knowledge that he risks being gored. Only then is writing worthwhile. But how can the writer achieve this invigorating sense of mortal danger? Leiris's answer is: through self-exposure, through not defending himself; not through fabricating works of art, objectifications of himself, but through laying himself—his own person—on the line of fire. But we, the readers, the spectators of this bloody act, know that when it is performed well (think of how the bullfight is discussed as a preeminently aesthetic, ceremonial act) it becomes, whatever the disavowals of literature—literature. A writer who subscribes to a program similar to Leiris's for creating literature

Description: