Lucian: On the Syrian Goddess PDF

Preview Lucian: On the Syrian Goddess

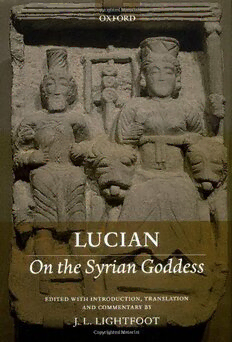

ISBN 0-19-925138-X I I 11 11 9 780199 251384 Cult relief ofA targatis, Had ad, and the UYJfL~i'ov from the temple ofA targatis, Dura Europos LUCIAN ON THE SYRIAN GODDESS Edited with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by J. L. LIGHTFOOT OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIV1lRSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford NewYork Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dares Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Siio Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ©]. L. Lightfoot 2003 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2003 All rights reserved. No part oft his publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope oft he above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data • Lucian, ofSamosata. [De de a Syria. English] On the Syrian goddess I by] .L. Lightfoot ; edited with introduction, translation, and commentary by J. L. Lightfoot p.cm. Includes bibliographical references. r. Hierapolis (Syria : Extinct city)-Religion. 2. Cults-Syria-Hierapolis (Extinct city) I. Lightfoot,J. L. 11. Title. BLro6o .L7813 2003 299'.275691-de21 2002074868 ISBN o-19-925138-X 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Typeset in Dante MT by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by T J. International, Padstow, Cornwall For Audrey Lightfoot Thomas Henry Lightfoot PREFACE THIS book started with the modest aim ofinvestigatingthe Herodoteanimitation in the treatise IIE pt Tijs .Evp{TJs fhov (De Dea Syria, henceforward DDS), ascribed to Lucian ofSamosata. It grew to this length because I found no other way to deal with the issues it raised. It is a periegetical text which purports to be an eyewitness account of a city in northern Syria, Hierapolis (modem Membij), which was sacred to a divine couple here called by the Greek names Hera and Zeus, but whose indigenous names were Atargatis and Hadad. It is written in Ionic Greek, and sets out to imitate the dialect, language, style, and mannerisms ofHerodotus, the father of History and one of the fathers of Periegesis literature. It is one of the most curious, and con tested, pieces ofi mperial prose literature, potentially the most important literary source for a religion of the Near East in its native setting under the Roman Empire. But nothing is straightforward about it, least of all its attribution to Lucian. The view taken of its authorship, in fact, is one of the most important determinants on the way it is read. I found an astonishing catholicity of opinion on the subject: on the one extreme, there are those who r~ad it as rip-roaring fantasy on the same level as the Tme Stories, arid on the other, those who take it for a pellucidly transparent window on the things it describes, with all possible shades ofo pinion in between. This situation reflects not, or not only, a healthy pluralism, but also a fracturing of opinion down fault-lines which reflect subject-divisions: Classics and Oriental Studies, Literature and History. To explicate the text is to attempt to cross more than one subject-divide. And it seemed to me, as I un covered the detritus of so much earlier opinion, insight, perplexity, and mis understanding, that this was important precisely as an interdisciplinary undertaking, an attempt to frame the subject in more mature terms than those which prevailed in a world where literary classicists did not talk to archaeologists of Roman Syria. For the very reason that it occupies a Hinterland in more than one subject area, this text is in the curious position ofbeing both famous and neglected. Classicists have not been aware of the material evidence, much of it archaeological, which helps to contextualise it, while orientalists and historians of religion have been largely unaware of its very complex literary background, on the one hand in the fifth-century BC historian Herodotus, and on the other of the second-century AD movement to resuscitate the Ionic dialect and imitate the old masters who had written in it. There is a very large literature on DDS, yet practically nothing in the way of detailed commentary. The only works with such pretensions are the badly outdated monographs by Garstang and Strong (1913) and Carl Clemen (1938); they have translations and miscellaneous observations, but no systematic X PREFACE exegesis. Further commentaries promised by Theodor Ni:ildeke and others never appeared. Apart from that, and the very occasional monograph on subjects raised by the treatise (a very honourable mention here goes to Robert Oden's Studies in Lucian' s De Syria Dea, 1977), most of the literature on DDS comes in the form either of specialist studies of particular, detailed points, or of asides in works devoted to other topics. I have read what I could find of this literature in order to produce a study and commentary on DDS which is as full as possible, and tries for the first time to do justice to both 'literary' and 'historical' aspects of the text (as if it were possible to divide the two down the middle). A great deal of material is now available on the cult of Atargatis, and it soon became obvious that, rather than have this emerge in a desultory fashion through out an overblown commentary, it would be far better to try to systematise it in an initial chapter. No synthesis of the evidence pertaining to Atargatis and related deities has yet been attempted, and my first section aims to provide at least a pre liminary one, on the basis of material published so far (for there is a great deal from sites such as Palmyra and Hatra which remains unpublished, and in some cases is in danger of being lost altogether). After that I turn to the text itself, and matters of genre, language, and style, ending with a discussion of the authorship issue and its implications for one of the main goals of the inquiry, the potential value of DDS as a historical source. In my third section, I present a new text of DDS, based on fresh collation of all surviving manuscript sources, together with a translation whose aim is not simply to reclaim the text from the virtuosic un readability of the Loeb, but also to offer an interpretation of the many small uncertainties and ambiguities lying just below the surface oft he Greek prose. The commentary itself takes up the second half of the book. Of the debts I have incurred in writing this book, three stand out. The first is to Stephanie West, who put me onto the subject in the first place, and drew my attention to certain works which would otherwise have taken me much longer to find. The second is to Peter Fraser for putting at my disposal the key to the Ashmolean library (the old library, before it turned into the Sackler): anyone familiar with its resources will understand just what this implied. This book was written mostly in the second half of a Prize Fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford. When All Souls awarded me a post-doctoral fellowship, Peter Fraser claimed credit for at least 1% of my success. I should like to assure him that, based on the length of time I held the key each week, he deserves 42.9% of the credit, precisely. The third major debt is to Ted Kaizer. Throughout this project, he shared published and unpublished material, put at my disposal his stunning collection of slides of the Roman Near East, shared his enthusiasm for travelling, and in general provided warmth, hospitality, and intellectual stimulation on a scale that his modesty would undoubtedly prevent him from recognising. I have also been helped in various ways by David Bain, Sebastian Brock, Stephanie Dalley, Matthew Dickie, Simon Digby, Lucinda Dirven, Thomas Earle, Jas Elsner, John Healey, W. G. Lambert, Fergus Millar, Donald Russell, Ian