I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! PDF

Preview I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!

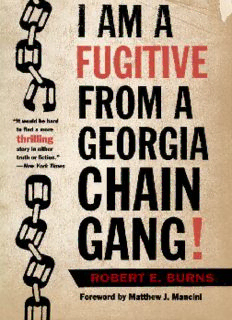

I AM A FUGITIVE FROM A GEORGIA CHAIN GANG! This page intentionally left blank ROBERT E. BURNS I AM A FUGITIVE FROM A GEORGIA CHAIN GANG! Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition by Matthew J. Mancini BROWN THRASHER BOOKS THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS ATHENS AND LONDON Published in 1997 as a Brown Thrasher Book by the University of Georgia Press Athens, Georgia 30602 Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition © 1997 by the University of Georgia Press All rights reserved The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Printed in the United States of America 01 00 99 98 97 P 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Burns, Robert Elliott. I am a fugitive from a Georgia chain gang! / Robert E. Burns : foreword to the Brown Thrasher edition by Matthew J. Mancini — Brown Thrasher ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Vanguard press, 1932. “Brown Thrasher books.” ISBN 0-8203-1943-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Burns, Robert Elliott. 2. Criminals—Georgia—Biography. 3. Convict labor—Georgia. I. Title. HV6248.B79A3 1997 365'.6'092—dc21 [B] 97-14202 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! was originally published in 1932 by the Vanguard Press and The Macfadden Publications, Inc. ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-4301-3 FOREWORD TO THE BROWN THRASHER EDITION MatthewJ. Mancini I RC)BERT E. BURNS'S account of his capture, imprisonment escape, recapture, reimprisonment, and second escape is a classic of American prison autobiography. It is a tale of devotion and betrayal, courage and cowardice, liberty and ser- vitude, imprisonment, flight, and deliverance—with quite a bit of violence and more sex thrown in than was expected in a memoir of 1932. The book caused a great sensation, and al- most as soon as it was published it was made into a stirring movie directed by one of Hollywood's leading directors and starring one of the greatest film actors in Hollywood history. In fact, it was probably the finest film to come out of Holly- wood in 1932. The author, Robert Elliott Burns, was a short, skinny, feisty, and excitable New Yorker with a tenth grade education and a restless ambition for success and respectability. Photographs of the celebrated fugitive from about the time of the books origi- nal publication show a neat, stylish dresser with sharp, hand- some features and hair combed straight back from a high fore- head. In 1917 Burns was in his middle or late twenties and still somewhat adrift.1 In 1912 he'd left his Brooklyn home and wandered for years without contacting his family, subsisting on meager wages as a Great Lakes sailor and a farm laborer. Two days after the United States entered World War I, Burns enlisted in the Army. Undoubtedly, like thousands of other vi Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition young men, he viewed the war as a means of escape from a stodgy future in the same city and neighborhood where he'd been raised. But—again like thousands of other young men— he found that the war provided him not with escape but with hell on earth. Burns served in the medical detachment of an engineering regiment that saw action in every major American engagement of the Great War—Château-Thierry, the Argonne, and St. Mihiel—was wounded, and emerged from the harrow- ing experience with his nerves shattered and his future as un- certain as ever. According to his rather sanctimonious brother, Vincent, Burns was "a typical shell-shock case" when he returned from the front.2 But Robert himself never made too much of his nervous condition and attributed his lamentable ordeal to a combination of his own actions and the treachery of others, whether low-life criminals or highly placed public officials (indeed, in Burns's narrative it is often hard to tell those two types apart). However tenuous his psychological condition was, Burns's tale did have an aura of fate or destiny about it that struck a resonant chord with the men and women of his gen- eration, especially after the start of the Depression. And the tale Burns has to tell is truly amazing. He returned from the war to find his job and his sweetheart taken by other men. The old tendency to wander reasserted itself; combined with his mental condition, it led to a second departure from Brooklyn, prolonged homelessness, and, ultimately, to an ob- scure Atlanta flophouse. There he was tricked into participat- ing in a pathetic robbery that netted its three perpetrators the princely sum of $5.81. The three were abruptly arrested and swiftly convicted, which in Georgia in 1921 meant sentenced to hard labor on the infamous chain gang. Burns's appalling sentence: six to ten years. Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition vii The reason the sentence was so dreadful, and that doing time in Georgia was so notorious, can be traced to a simple fact: the State of Georgia did not have a prison. Indeed, it had not had one since 1874, and would not acquire one until 1938. To understand the full implications of Burns's predicament, then, it is necessary to draw back into the recesses of the curious and depressing history of crime and punishment in Georgia. In the administrative and fiscal chaos of post—Civil War Georgia—as in the entire South—legislators, at once desper- ate and uncaring, chose to deal with the problem of criminal punishments by tossing it aside. They passed and enforced new laws that established an entirely different kind of prison system. Under the new regime, convicts were leased to both individuals and corporations, who undertook to maintain and guard them while the convicts themselves provided the labor the now slaveless South so desperately needed. Most states had no prison building at all, and in those that did, like Texas and Arkansas, the structures were so tiny, dilapidated, and under- staffed that they played only a minor role in those states' crimi- nal justice systems. Such was the institutional ancestry of the inaccurately named "prison" system in which Burns found himself enmeshed in 1921. Its results were horrific. Prisoners were scattered all over the state in small squads and large gangs, on plantations, coal mines, sawmills, and brickyards. There the mostly black work force endured foul shacks, putrid food, backbreaking labor, bru- tal punishments with whip and stocks, and sometimes literal torture. As the years passed, prisoners' sentences grew ever longer, while the ever-younger convict population doubled, then tripled, and by the 1890s grew to ten times its pre—Civil War size. Escape and death rates together averaged six percent annually—for forty years. viii Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition During the 1880s and 1890s, a slight variation on this kind of convict forced labor began to emerge in Georgia. It was simultaneously officially conducted and completely illegal. Georgia's counties were in need of labor on public works and were under pressure from smalltime contractors to provide them with labor (just as the state was pressured by big corpo- rations); and so the counties began leasing their own prisoners to those smaller operators. These county convicts were petty criminals who had been convicted of misdemeanors and had sentences of less than one year, in contrast to the state prison- ers, who had felony convictions and much longer sentences (in 1890, for example, nearly half of the state prisoners had sen- tences often years or more). The practice of leasing county convicts was unambiguously against the law. A statute of 1879 outlawed it, and two sepa- rate decisions of the state supreme court reaffirmed the ban, but to no avail. As late as 1908 the state's Prison Commission was still complaining to the governor that it had "for ten consecutive years, in each of its annual reports, reported such [county] chaingangs to the General Assembly as being orga- nized and conducted illegally, and contrary to law, and that it had no power or authority to break them up, or impose fines."3 It is in these county-based chain gangs that we can see the real seeds of Burns's prison experience. In 1908, amid much fanfare and self-congratulation, the Georgia legislature abol- ished the convict lease, which had not only defined the states prison policies but had increasingly come to symbolize the state's alleged backwardness in other regions of the country. But the abolition legislation was hardly a paradigm of humanitar- ian reform, as so many officials, North and South, tried to make it seem at the time. Instead it was a means of providing the plaintive, labor-deprived counties with the workers that the Foreword to the Brown Thrasher Edition ix legislature and the courts had so long denied them but which they took anyway. According to the 1908 law, the state con- victs would simply be parceled out to counties, which would construct labor camps to house and feed the prisoners. The new plan had something for everyone. Counties gave up the illegal practice of leasing their misdemeanants, and in compensation, so to speak, the state turned over its felons to the counties for hard labor. The state could engage in a charade of progressive reform while not incurring any cost, the counties could have access to convict labor without those bothersome legislative in- vestigations, and the citizens could enjoy better roads, bridges, and other public works at rock-bottom tax rates. Even the cor- porations that had leased state convicts were satisfied, because by 1908 the costs of the leasing contracts had risen to about the level of the wage bill for free unskilled labor anyway. Serious students of southern history may safely ignore Burns s attempt to explain the historical origins of his predicament (193—95).4 It is an unsteady compound of hearsay, myth, and stereotype that hardly touches on the realities of race, political corruption, economic calculation, public administration, or the material conditions of the convict camps. But he was accurate in asserting that "today, the county is the contractor. Although the county does not pay the State any money for the use of the convicts, they are compelled to clothe, feed, and house the prisoners at the county expense" (195). This was the essence of the new system that went into effect in 1909, just a dozen years before Burns's conviction. Believing his sentence to be literally unendurable, Burns devised an ingenious and successful escape plan, which is re- counted here in thrilling, vivid detail. After a desperate flight, he made his way to Chicago, and there, over a period of seven years, he remade himself. He worked, sweated, saved, bought

Description: