Hugo Munsterberg on Film: the Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings PDF

Preview Hugo Munsterberg on Film: the Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings

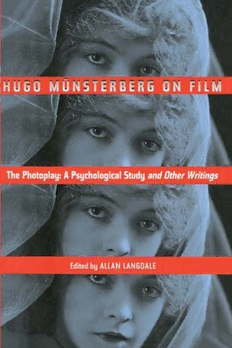

Hugo Munsterberg on Film The Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings Edited by ALLAN LANGDALE Routledge New York London 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Contents Acknowledgments v Editor's Introduction S(t)imulation of Mind: The Film Theory of Hugo Miinsterberg Allan Langdale I The Photoplay: A Psychological Study Introduction I The Outer Development of the Moving Pictures 45 2 The Inner Development of the Moving Pictures 54 Part 1: The Psychology of the Photoplay 3 Depth and Movement 4 Attention 5 Memory and Imagination 6 Emotions Part II: The Aesthetics of the Photoplay 7 The Purpose of Art I09 8 The Means of the Various Arts I20 9 The Means of the Photoplay I28 I 0 The Demands of the Photoplay I39 II The Function of the Photoplay IJI iii Contents Additional Writings and Texts Margaret Miinsterberg on The Photoplay Why We Go to the Movies Hugo Munsterberg Peril to Childhood in the Movies Hugo Munsterberg Interview with Hugo Miinsterberg 20I Speech on the Paramount Pictographs 204 Index 207 iv Acknowledgments There have been several people who encouraged me in my plan to offer a new edition of Hugo Miinsterberg's The Photoplay: A Psycho logical Study. My first exposure to the text was several years ago in Edward Branigan's film theory class at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and Edward's energetic promotion played a central role in the realization of the project. Similarly, Constance Penley has for many years advocated my interest in film studies, and Chuck Wolfe helped greatly with his support during my search for a pub lisher. Edward Branigan, Chuck Wolfe, Melinda Szaloky, Lisa Parks, and Dore Carter lent invaluable advice during the editing process, and I am very thankful for their efforts. I would also like to thank William Germano for embracing the proposal and making it possible for a new generation of film scholars and students of the history of psychology to have access to The Photo play and to these supplementary writings of Hugo Miinsterberg. Joe Palladino deserves mention for his kind encouragement, while Chris Husted can be credited with applying unrelenting pressure on me to undertake the reissue. They all have my sincere gratitude. I am indebted to the staff of the Special Collections department of the Boston Public Library who were generous with their Miinsterberg archive materials. I would also like to extend thanks to Frank A. J. L. James of the Royal Institution for assisting me with an important ref erence and the mysterious web-based personage "Mr. X," who tracked down another article I had trouble locating. The book could not have been completed without the kindness of Suzanne and Reece Duca and the unwavering support of my mother, Nancy. Finally, I would like to thank the students of the film studies department at UCSB, who have been a source of continual energy and inspiration. v S(t)imulation of Mind: The Film Theory of Hugo Mi.insterberg Allan Langdale ... films have the appeal of a presence and of a proximity that strikes the masses and fills the movie theaters. This phenomenon, which is related to the impression of reality, is naturally of great aesthetic sig nificance, but its basis is first of all psychological.1 -Christian Metz In July of 1930 Welford Beaton published an article provocatively titled "In Darkest Hollywood" in The New Republic. In it he enthusi astically champions a book, published 14 years before, which sadly seems to have already disappeared from sight: Neither in the main Hollywood library nor in any of its branches can a copy of this book be found. It is not for sale in a Hollywood book store. I have not encountered a dozen people who have read it, or two dozen who have heard of it. The film industry is one of tremen dous proportions, yet this great contribution to its mentality is out of print.2 The great contribution Beaton was referring to was The Photoplay: A Psychological Study, written by one of the leading figures in the field of psychology, Hugo Miinsterberg.3 Forty years after Beaton's lament, in the introduction to the 1970 Dover reprint of Miinsterberg's book, Richard Griffith also noted the book's disappearance.4 One could write those same words of Beaton's today, but in the thirty-one year interim since the Dover edition there has been modest but significant attention devoted to Miinsterberg in Hugo Miinsterberg on Film general and to The Photoplay in particular.5 The book is regarded by many to be the first serious piece of film theory, and is one of the first books to argue for the potentialities of film as an independent art form. 6 Few would dispute its important place in the history of film theory. Yet this significant piece of early film theory has been largely unavailable to the current generation of film students and scholars-to say nothing of students of psychology and philosophy for whom this book should also hold substantial interest. It is with this in mind that we have published a new edition of The Photoplay along with a num ber of supplementary writings by Miinsterberg on film, none pub lished in English after their original appearance in the years 1915 to 1917.7 Included is an interview as well as a speech by Miinsterberg8 and a piece entitled "Why We Go to the Movies," which is an excur sion into film that prefigures The Photoplay.9 Another article, "Peril to Childhood in the Movies," deals with the issue of the effects of film violence on children. This essay not only reflects attitudes towards film violence in the early 20th century, but is a revealing expression of Miinsterberg's social idealism.10 Also included is the section on The Photoplay from Margaret Miinsterberg's 1922 biography of her father, an admiring remembrance composed by a daughter attempting to record a definitive and positive portrayal of a man America had since turned its back upon.11 Today, relatively few people in the disciplines of film studies or psychology know very much about Hugo Miinsterberg and yet around 1915 he was probably the most famous academic in the United States. His books were widely read and his ideas discussed in broad circles.12 One of the first students of the emerging school of experimental psychology in his youth, Miinsterberg later distinguished himself as the founding father of applied psychology.13 Miinsterberg is well known for his books and articles on the subject, including Vocation and Learning (1912), Psychology and Industrial Efficiency (1912), Busi ness Psychology (1915), and Psychology: General and Applied (1916).14 He developed psychological tests to help the Boston Elevated Rail way Company find the least accident prone drivers for their trolleys, 2 S(t)imulation of Mind and composed similar experiments for the Hamburg American Ship ping Company to test for those persons who would make the best ship captains.15 To place The Photoplay in a historical and biographical context, some details of Miinsterberg's life and career should be considered.16 Hugo Miinsterberg was born in Danzig in 1863, the son of a Jewish lumber merchant, Moritz Miinsterberg, and his second wife Anna. He had two older brothers, Otto and Emil-who had been born to Moritz's previous wife, Rosalie-and one younger brother, Oskar.17 The family's central tragedies were the deaths, first, of Rosalie, then of Anna in 1875 when Hugo was twelve years old. This loss, accord ing to Phyllis Keller in her largely psycho-biographical account of Miinsterberg's life, had profound effects on his personality and atti tudes.18 He developed a great desire to please his father-perhaps in consolation for their mutual loss-but he also developed a fear of abandonment and rejection, a fear that, as we shall see, was ultimately realized on a grand scale later in his life. His early education was eclectic and ranged between arts and sciences; he studied languages, music, wrote stories and poetry, and was interested in archaeology, botany, and read widely in literature. In the years after the death of his father in 1881, Miinsterberg adopted a strident nationalism and began to idealize the role of culture in the perfecting of German soci ety.19 He also embraced scholarship and increasingly began to identify himself with academic success, being the only one of the Miinsterberg sons to complete his Gymnasium training and to pass his Abitur exam inations, thus opening the door to an academic career.20 Along with his two younger brothers, Miinsterberg was baptized shortly after the death of his father; a decision, as Matthew Hale notes, that was not at all uncommon in German society in the late 19th century since adher ing to one's Judaism could severely curtail a young man's institutional ambitions, including attending a university. 21 Miinsterberg's academic training began in 1882 with the study of medicine in Leipzig where, in the summer of 1883, he heard lectures by the major figure in German experimental psychology, Wilhelm 3