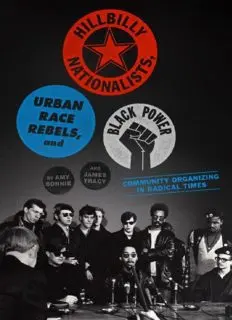

Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times PDF

Preview Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR HILLBILLY NATIONALISTS, URBAN RACE REBELS, AND BLACK POWER “Hillbilly Nationalists recovers the voices of white, working-class radicals who prove abolitionist John Brown’s legacy is alive and well. Over ten years, Sonnie and Tracy have collected rare documents and conducted interviews to fill a long- missing piece of social movement history. Focusing on the 1960s–70s and touching on issues just as relevant today, these authors challenge the Left not to ignore white America, while challenging white America to recognize its allegiance to humanity and justice, rather than the bankrupt promises of conservative politicians.” —ANGELA Y. DAVIS, AUTHOR OF ABOLITION DEMOCRACY: BEYOND PRISON, TORTURE AND EMPIRE “This book is, without question, the definitive resource for scholars, students, and activists interested in some of the most innovative and understudied coalitional politics of the New Left.” —DARREL ENCK-WANZER, EDITOR OF THE YOUNG LORDS: A READER “In our world, ‘white, working-class anti-racism’ is considered an oxymoron, or at best a pipe dream. Amy Sonnie and James Tracy prove these assumptions wrong, excavating a forgotten history of poor white folks who, in alliance with black nationalists, built a truly radical movement for social justice, economic power, and racial and gender equality. They have written a beautiful, powerful, surprising account of class-based interracial organizing; I expect Hillbilly Nationalists to inspire a new generation of activists who understand that a true rainbow coalition is not only desirable but our only hope.” — ROBIN D. G. KELLEY, AUTHOR OF FREEDOM DREAMS: THE BLACK RADICAL IMAGINATION AND THELONIOUS MONK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL “Sonnie and Tracy are master storytellers whose stories of working-class, interracial solidarity chart a new direction in the history of the modern freedom movement. Based on dozens of oral histories and previously untapped personal records of movement activists, this book offers an inspiring and largely invisible history of poor and working-class whites who built a ‘vanguard of the dispossessed’ with Black Panthers, Young Lords, and others in the radical movement for racial and economic justice. Written with nuance and power, this is a major contribution to the study of civil rights, social justice, working-class communities, and the politics of whiteness in the United States.” —JENNIFER GUGLIELMO, AUTHOR OF LIVING THE REVOLUTION AND ARE ITALIANS WHITE? “Hillbilly Nationalists is the story of reformers and revolutionaries, dreamers and doers, who remind us of a transformative organizing tradition among white, working-class communities. Inspired by Black Power and global events, these organizers did what only poor folks can do: they pooled their resources to build a vibrant social movement that escapes easy classification. Sonnie and Tracy combine first-rate historical research and extensive oral histories to capture the legacies of those unsung heroes and heroines who battled for the hearts and minds of working-class Americans in the 1960s and 1970s.” — DAN BERGER, EDITOR OF THE HIDDEN 1970s: HISTORIES OF RADICALISM AMY SONNIE is an activist, educator and librarian who has worked with U.S. grassroots social justice movements for the past 17 years. She is cofounder of the national Center for Media Justice. Her first book, Revolutionary Voices, an anthology by queer and transgender youth (Alyson Books, 2000), is banned in parts of New Jersey and Texas. Her work has appeared in the San Franscisco Bay Guardian, Alternet, Philadelphia Inquirer, Clamor, the Oxygen Television Network, Bitch magazine, and The Sojourner. JAMES TRACY is a longtime social justice organizer in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is the founder of the San Francisco Community Land Trust and has been active in the Eviction Defense Network and the Coalition On Homelessness, SF. He has edited two activist handbooks for Manic D Press: The Civil Disobedience Handbook and The Military Draft Handbook. His articles have appeared in Left Turn, Race Poverty and the Environment, and Contemporary Justice Review. ROXANNE DUNBAR-ORTIZ (Foreword) grew up in rural Oklahoma, daughter of a landless farmer and a half-Indian mother. She is Professor Emerita in the Department of Ethnic Studies at California State University East Bay, and author of numerous books on Indigenous peoples’ histories, as well as three acclaimed historical memoirs: Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie; Outlaw Woman: A Memoir of the War Years, 1960-1975; Blood on the Border: A Memoir of the Contra War; and Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico, 1680-1980. Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times © Amy Sonnie and James Tracy Foreword © Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz All rights reserved First Melville House Printing: September 2011 Melville House Publishing 145 Plymouth Street Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.mhpbooks.com eISBN: 978-1-61219-008-2 Cover photo: the original Rainbow Coalition on April 4, 1969, at a press conference urging interracial unity on the one-year anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination. Standing, from left to right: Andy Keniston, Hi Thurman, William Fesperman, Bobby McGinnis, Mike James, Bud Paulin, Bobby Rush, Elisa McElroy and Alfredo Matias. Seated: Junebug Boykin, Nathaniel Junior, Luis Cuzo. Courtesy of Michael James Archives. v3.1 Contents Cover About the Authors Title Page Copyright List of Abbreviations Foreword by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Epigraph Introduction Chapter 1 The Common Cause Is Freedom: JOIN Community Union and the Transformation of Peggy Terry Chapter 2 The Fire Next Time: The Short Life of the Young Patriots and the Original Rainbow Coalition Chapter 3 Pedagogy of the Streets: Rising Up Angry Chapter 4 Lightning on the Eastern Seaboard: October 4th Organization and White Lightning Epilogue Acknowledgments & Interviews Notes List of Abbreviations BYNC Back-of-the-Yards Neighborhood Council CFM Chicago Freedom Movement COINTELPRO Counterintelligence Program [of the FBI] CORE Congress of Racial Equity ERAP Economic Research and Action Project HRUM Health Revolutionary Unity Movement JOIN Jobs or Income Now LID League for Industrial Democracy NAACP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People NWBCCC Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition NWRO National Welfare Rights Organization O4O October 4th Organization PFP Peace and Freedom Party PL Progressive Labor [Party] RYM / RYM IIRevolutionary Youth Movement SCEF Southern Conference Educational Fund SCLC Southern Christian Leadership Conference SDS Students for a Democratic Society SNCC Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee UPWC United Parents Who Care Foreword BY ROXANNE DUNBAR-ORTIZ I first met representatives of the New Left at San Francisco State College (now University) in the Spring of 1961, my first semester there. I was twenty-two years old, having moved to San Francisco from Oklahoma with my husband. During 1960, my first year living in San Francisco and working fulltime in an office machine repair factory, I followed the television images of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in the South and all over the country and I was ripe for recruitment to the Movement. In particular, I closely watched the local anti- death penalty sit-ins at San Quentin prison to prevent the execution of author- inmate Caryl Chessman, and followed the student demonstrations against the House Un-American Activities Committee at San Francisco City Hall as police attacked hundreds of students with batons, blasting them with fire hoses and arresting dozens. I wanted to meet those brave young people. I had long hungered to go to college and now it seemed like a way to get involved with the Movement too—I was thinking less about the risk and more about my excellent typing skills. So, that day on the San Francisco State campus when I saw an information table about the Mississippi Freedom Rides, I thought, “Finally!” After a full year in San Francisco, this was the first seemingly public invitation to join. Back in Oklahoma I came from a childhood of rural poverty. For my last year of high school I moved from “the sticks” to work full time in Oklahoma City, which meant I attended the trade high school, secretarial track of course. It was the first year of school desegregation in Oklahoma, a year after the Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, which ordered the desegregation of public schools. I attended the first public school in Oklahoma to integrate. It was no accident that the single wholly working-class white school received that honor. Predictably, there were acts of white racist violence against the few Black students. I began to pay attention to the sit-ins at local drugstore counters. I read the local extremely rightwing newspaper, because that was the only one available, but the photographs spoke for themselves about the violence being meted out against Black people all over the South. Then, I married into a family that abhorred racial discrimination. My father-in-law, a New Deal Democrat, had been a leader in efforts to desegregate the local crafts unions. From my in- laws’ point of view, “lower-class” whites were the racist culprits, the kind of people I came from. I nearly held my breath for three years until I could leave Oklahoma and my past forever. I hoped San Francisco would be free of “racist low-class” white people. In San Francisco everything seemed possible. Attending college was a dream come true and here, during my first semester, I found the noble activists I hoped had all the answers. Without knowing it, they intimidated me to the core. Behind the table sat two handsome young white men wearing jeans and plaid shirts. Standing behind them were two young women with long, straight blonde hair, dressed in black turtlenecks, skirts and leotards with shiny black boots. They were all laughing and talking with each other. I felt thrilled, as if a whole new world lay before me. I was also panic-stricken, not knowing what to say. (I look back and see, through their eyes, this working-class young woman dressed in the style of the new first lady, Jackie Kennedy, in a pastel linen shift and matching cardigan sweater with matching purse and medium high heels, panty hose, of course, and a bouffant hairdo. And then, out came the pronounced Okie accent when she got up the nerve to speak). I fingered a flyer on the table that asked for donations to send freedom riders—Black and white students on northern buses— to Mississippi to protest segregated interstate transportation. It seemed a brilliant but dangerous program. They also had a sign-up sheet for volunteers. How I wanted to sign! Suddenly, I heard my voice asking if they were going to talk to poor whites in the South. They seemed stunned by the question, perhaps thinking I was joking. But, my surely terrified face and trembling hands must have made clear that I was serious, and that I was myself one of the poor whites. Immediately, I wished I could take back the question and start over. Then, one of the young men said, “No,” and added that they weren’t recruiting them either. It seemed I had spoiled my attempt to somehow join the cause. It took several years before I tried to get involved again—only after I had successfully gotten rid of my accent, changed my way of dressing, grown my hair long and driven the working-class rural Okie girl underground in order to be accepted by the Movement. My experience is perhaps exceptional, but only because most individuals from my kind of background instinctively avoided putting themselves in positions of such humiliation and rejection. I am glad I persisted in my radical commitment, but the truth is that the Movement was, and still is, mired in class hatred. One of my mentors, the late