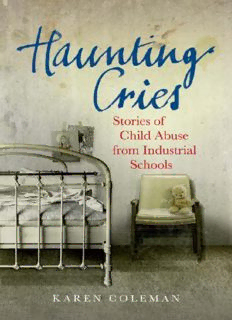

Haunting Cries. Stories of Child Abuse from Irish Industrial Schools PDF

Preview Haunting Cries. Stories of Child Abuse from Irish Industrial Schools

This book is dedicated to all those children who were abused in Irish religious institutions. CONTENTS Cover Title page Dedication Chapter 1: Exposing the Abuse: The Ryan Report, May 2009 Chapter 2: Noel Kelly and Daingean Chapter 3: Michael O’Brien and Ferryhouse Chapter 4: The Girl with the Broken Heart: Teresa Gormley and the Sisters of Mercy Chapter 5: The Boy with the Broken Arm: Mickey Flanagan and Artane Chapter 6: ‘John Brown’ and Upton and Letterfrack Chapter 7: Marie Therese O’Loughlin and Goldenbridge Chapter 8: Tommy Millar and Lenaboy and Salthill Chapter 9: Martina Keogh and Clifden and the Magdalene Laundries Chapter 10: Still Looking for Justice: John Kelly Chapter 11: Maureen Sullivan and the Magdalene Laundries Chapter 12: From Homelessness to Hope: Gerry Carey Chapter 13: The Abusers: How and Why? Chapter 14: Rough Justice: The Residential Institutions Redress Board Chapter 15: A Reputation in Tatters: The Catholic Church in Ireland Notes Acknowledgments Author’s Note Copyright About the Author About Gill & Macmillan Chapter 1 EXPOSING THE ABUSE: THE RYAN REPORT, MAY 2009 T here is a lane in the heart of Connemara, Co. Galway that leads from the village of Letterfrack up into a wooded area, where a small graveyard is tucked behind the trees and hidden from the main road. A narrow gateway opens onto a patch of ground where small headstones in the shape of black marble hearts nestle in the grass. Each headstone carries the name of a boy and the year he died. Seventy-nine boys are buried there in total; all were inmates of the notorious Letterfrack Industrial School that was run by the Christian Brothers. The first boy buried there died in 1891; the last in 1956. Their ages range from four to 16. This graveyard is not a place of rest. It is instead a burial ground of abuse where the ghosts of the boys interred there seem to hover in silence as the visitor sheds tears for their stifled cries for help. It is a place laden with such profound sadness it provokes a speechless mix of disbelief and guilt; disbelief that religious orders could have been capable of such gross inhumanity against children in their care, and guilt at being part of a State that participated in that abuse through ignorance, poverty and negligence. Letterfrack Industrial School graveyard is a spine-chilling illustration of religious child institutional abuse and an example of how Ireland allowed vulnerable children to be destroyed by tormentors masquerading as guardians. A walk along the lines of black hearts reveals a journey of suffering. Young lives struck down year after year. In 1918 alone 10 boys died in Letterfrack Industrial School; seven died within 20 days of each other in that year. Those seven boys included Michael Bergin, who died on 13 November 1918. He was 15. Michael Sullivan died seven days later. He was 14. Joseph Boxan shut his eyes for the last time on 26th of that month. He was nine. And Thomas Hickey was only 10 when he died on that same day. Two days later Michael Walsh took his last gasp at just 11 years of age. He wasn’t the only one to die that day. Anthony Edward, who was the same age as Michael, also passed away. that day. Anthony Edward, who was the same age as Michael, also passed away. Four days later William Fagan’s life was also cut short when he was only 13. Today they all lie together in Letterfrack. The Christian Brothers put these boys’ deaths down to influenza-pneumonia. That explanation may be plausible; after all the Spanish flu of that era claimed millions of lives worldwide. But the boys’ premature deaths occurred against a backdrop of unremitting hardship at Letterfrack, where a climate of fear propagated tyrannical and sadistic behaviour among the Christian Brothers running the place. One hundred boys are estimated to have died in Letterfrack from the time it first opened its doors for business in 1887 to its closure in 1974. For decades stories of abuse told by former inmates of industrial schools such as Letterfrack were dismissed by many in Ireland as the false rants of people embittered by their circumstances. But on 20 May 2009 their accounts were finally vindicated when the report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse1 was published. The five-volume tome is a shocking account of child abuse that took place in religious industrial and reformatory schools and other institutions from the 1930s up to the time of their closure. The brutality of Letterfrack cited in the Ryan Report exposed Ireland’s dreadful history of child neglect. Physical, emotional and sexual abuse were systematic there. Punishments were meted out for minor misdemeanours. Boys were battered by Brothers who abused their positions of power and vented their anger on children too poor and vulnerable to complain. Inmates who absconded in winter were hauled back, stripped of their clothes, hosed down in the yard and left to stand in the freezing cold in their underpants for hours; other absconders had their heads shaved and were subjected to perverse forms of solitary confinement, which meant their fellow inmates couldn’t talk to them until their hair had grown back. Bed-wetters were ordered to drag their wet mattresses out into the open yard where they were humiliated by their fellow inmates. Boys were lashed with leather exposing the abuse straps, tyres, fists, legs and whatever other instruments of torture the Brothers could get their hands on. They were made to work as child slaves on the bogs and in the workshops and they were never paid for any of their hard labour. The Christian Brothers who didn’t participate in this sadistic type of cruelty colluded in it by remaining silent. Few spoke out against their superiors and even when they did their pleas were largely dismissed. The reputation of the Church and the Congregation took precedence over any form of justice for the children in their care. One former resident of Letterfrack told the Ryan team about the reign of terror that pervaded the school when he was there in the 1950s and early 1960s. From the time you went into that you lived in fear, you were just constantly terrified. You lived in fear all the time in that school, you didn’t know when you were going to get it, what Brother was going to give it to you, you just lived in fear in that school.2 Another former resident described how ‘it was awful, it was very very cold, it was very very lonely, but the worst thing about it all, it was so scary’.3 Letterfrack’s endemic violence cultivated a culture of bullying among the boys themselves with peer sexual abuse at the extreme end of the spectrum. … you had to fight for survival because there was a lot of bullying and a lot of stuff going on. You had to be on your guard all the time because there was bigger kids and stronger kids, different kids and different types. Rough kids and bad kids; there was all different types. Yes, it was dog eat dog. It was survival, you had to do everything to survive, you know. You had to fight, scratch, you had to do everything for survival. There was no love or affection or caring from anyone, you know. And there was no one to talk to, you just had to form your own way of survival.4 Letterfrack was one of 21 religious institutions extensively documented in the Ryan Report. Its publication shocked the Irish nation; people reeled with disbelief as they read about the staggering levels of physical, sexual and emotional cruelty children endured in these ghastly places since the 1930s. The Report shook the already battered reputation of the Catholic Church and it highlighted the negligent role the Irish State played in the incarceration and abuse of children. In the weeks following the Report’s publication, people tried to comprehend how vulnerable children could have been treated in such an appalling way. Ireland was swamped by a tsunami of shock and grief. The Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse marked a watershed in contemporary Irish history. It validated the stories of religious brutality that former residents of these institutions had been describing for years and it raised numerous questions about the Catholic Church, the Irish State and Irish society. People wondered what kind of a country they were living in and even the most committed Irish Catholics questioned their faith. The Report was the result of a nine-year investigation into the treatment of children in institutions run by religious orders from the 1930s to the present day. The nuns and Brothers who abused their power in these hellholes were exposed as sadists and rapists, bullies and misfits. The Ryan Report showed how the lives of thousands of people had been destroyed in these pious prisons, supposed to be institutions of care. The Report blew apart the smokescreen of moral perfection that the religious orders had hidden behind for decades and it illuminated the hypocrisy of their self- had hidden behind for decades and it illuminated the hypocrisy of their self- righteous preachings. The Report’s executive summary confirmed a legacy of reprehensible neglect and brutality in the institutions investigated. Ryan concluded that the incarceration of children in these miserable places was ‘an outdated response to a nineteenth century social problem’.5 They were like Dickensian prisons where children went to bed hungry because the food was inadequate, inedible and badly prepared. Ryan declared that schools depended on ‘rigid control by means of corporal punishment’6 and that the harshness of the regime was ‘inculcated into the culture of the schools by successive generations of Brothers, priests and nuns. It was systemic and not the result of individual breaches by persons who operated outside lawful and acceptable boundaries.’7 Fear was the instrument of control in these institutions where, in many schools, ‘staff considered themselves to be custodians rather than carers’.8 Witnesses to the Ryan investigation team spoke of scavenging for food from waste bins and animal feed.9 Bullying was widespread in boys’ schools, where the younger inmates were frequently deprived of food as the older boys grabbed their rations. Children were badly clothed and they were left in soiled and wet work clothes throughout the day. Accommodation was cold, spartan and bleak and the children slept in large unheated dormitories with inadequate bedding.10 Sanitary conditions were abysmal and little provision was made for menstruating girls. The children received completely inadequate education in these tyrannical institutions. The Ryan Report found that in the girls’ schools, children were removed from their classes in order to perform domestic chores or work in the institution during the day.11 Instead of providing basic industrial training, the institutions cynically profited from the children by using them as child labour on farms and in workshops. The Report showed how a climate of fear pervaded these industrial and reformatory schools where physical abuse was systematic. The Brothers and nuns engaged in excessive beatings, sometimes with implements designed to deliver maximum pain. Children lived with the daily terror of not knowing where the next beating was coming from.12 Girls were frequently left shaking with fear for hours in cold corridors as they waited for their veiled executioners to deliver their frenzied lashings. Absconders were treated with particular ferocity. Their heads were shaved and they were flogged savagely for daring to escape from their sadistic custodians. The Report exposed how the Department of Education failed abysmally to investigate why children were absconding from the schools. Had they bothered to do so, they could have revealed decades of abuse and prevented thousands more children from enduring lasting damage. Ryan concluded that sexual abuse was endemic in the boys’ institutions and that the Congregations protected sexual predators and covered up their crimes to safeguard their own reputations. A culture of silence meant paedophiles were able to abuse with impunity and their behaviour was rarely brought to the attention of the Department of Education or the Gardaí. And even on the rare occasions when the Department found out about the sexual abuse, Ryan stated that it colluded in the silence:13 ‘There was a lack of transparency in how the matter of sexual abuse was dealt with between the Congregations, dioceses and the Department.’14 Paedophiles were shunted on to other institutions where they continued to prey on vulnerable children. When faced with accounts of abuse by former residents, Ryan declared that some religious orders remained defensive and disbelieving even in cases where men and women had been convicted in court and admitted to such behaviour: ‘Congregational loyalty enjoyed priority over other considerations including safety and protection of children.’15 The shameful cover-up went further. In some cases former Brothers with histories of sexual abuse continued their teaching careers as lay teachers in State schools after leaving the religious orders. Emotional abuse was widespread in these despotic establishments. Children were belittled and humiliated on a daily basis. Bed-wetters were forced to parade their soiled sheets in public. Ryan found that private matters such as bodily functions and personal hygiene were used as opportunities for degradation and humiliation.16 Children were told they were worthless and their families were denigrated. The psychological fall-out was enormous. Young girls and boys lived in constant fear of being beaten. Witnesses told the Ryan team how they were still haunted by the cries of other children being flogged excessively. Sibling bonds were smashed to smithereens as brothers and sisters were separated from one another. The remote locations of some of these austere institutions made it almost impossible for family visits and the unfortunate children unlucky enough to end up in these places felt abandoned by their parents and family members. Particularly vulnerable children, such as those with disabilities, were also abused in institutions like St Joseph’s School for Deaf Boys in Cabra in Dublin. Ryan described St Joseph’s as a ‘very frightening place for children who were learning to overcome hearing difficulties’.17 The Report found that corporal punishment was ‘excessive and capricious’ there and that the boys incarcerated in St Joseph’s suffered from sexual abuse from staff and older boys.18 The Ryan Report dominated the headlines over the days and weeks following

Description: