Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip PDF

Preview Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip

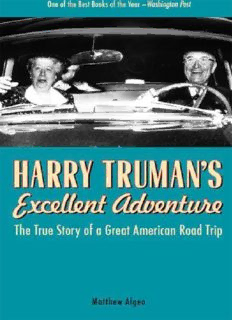

Praise for Harry Truman’s Excellent Adventure “Utterly likable.” —Christopher Buckley, Washington Post “A lively, humorous glimpse into an unlikely presidential vacation and a vanished era.” —History Magazine “Brassy, bright, energetic, brief, and declaratively American.” —Washington Times “An engaging account…. Well-researched.” —Wall Street Journal “This very readable book takes us back to a country quite different in many ways from today. Readers will feel almost like they’re sitting in the back seat of the 1953 Chrysler, enjoying the trip.” —BookPage “Algeo chronicles this unlikely excursion in great and wonderful detail…. [An] enchanting glimpse into a much simpler age.” —Library Journal “Charming.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch “Engaging.” —Booklist “With deliberate detours, this book is a portal into the past with layers of details providing unusual authenticity and a portrait of the president as an ordinary man.” —Publishers Weekly “An absolutely wonderful book.” —Virginian-Pilot “Now, this is what’s called a road trip.” —In Transit, New York Times travel blog “With this excellent road story, Algeo has helped preserve the essence of a great man.” —Jackson (MS) Free Press The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Algeo, Matthew. Harry Truman’s excellent adventure / Matthew Algeo. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-55652-777-7 ISBN-10: 1-55652-777-2 1. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972. 2. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Travel —United States. 3. Automobile travel—United States. 4. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Finance, Personal. 5. Presidents—Retirement—United States. 6. Presidents—United States—Biography. I. Title. E814.A75 2009 973.918092—dc22 [B] 2008040136 Cover design: Visible Logic, Inc. Interior design and cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Front cover photo: AP/Wide World Photos Map design: Chris Erichsen © 2009 by Matthew Algeo Afterword © 2011 by Matthew Algeo All rights reserved First hardcover edition published 2009 First paperback edition published 2011 Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-56976-707-8 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 To Allyson, the best girl ever. I like roads. I like to move. —Harry S. Truman Contents Preface 1 Washington, D.C., Inauguration Day, 1953 2 Independence, Missouri, Winter and Spring, 1953 3 Hannibal, Missouri, June 19, 1953 4 Decatur, Illinois, June 19–20, 1953 5 Indianapolis, Indiana, June 20, 1953 6 Wheeling, West Virginia, June 20–21, 1953 7 Frostburg, Maryland, June 21, 1953 8 Washington, D.C., June 21–26, 1953 9 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 26–27, 1953 10 New York, New York, June 27–July 5, 1953 11 Pennsylvania (or, Abducted), July 5–6, 1953 12 Columbus, Ohio, July 6–7, 1953 13 Richmond, Indiana, July 7, 1953 14 Indianapolis, Indiana, July 7–8, 1953 15 St. Louis, Missouri, July 8, 1953 Epilogue Postscript Afterword Acknowledgments Sources Bibliography Index Preface O n the afternoon of July 5, 1953, a slightly bored state trooper named Manley Stampler was patrolling a lonely stretch of the Pennsylvania Turnpike near the town of Bedford, about one hundred miles east of Pittsburgh. Around three o’clock, Stampler spotted a gleaming black Chrysler ahead of him in the left lane, with a line of cars behind it. The Chrysler was blocking traffic. It wouldn’t move over to the right lane. Pennsylvania law required—still requires, in fact—that traffic keep right, except to pass. Stampler zipped up the right lane, pulled alongside the Chrysler, and motioned for it to pull over. It was, in the trooper’s estimation, as routine as a routine traffic stop could be. The Chrysler obediently moved to the right shoulder and slowed to a stop, its tires crunching on the loose gravel. Stampler passed the car and parked in front of it. He stepped out of his cruiser, adjusted his wide-brimmed hat, and slowly strode back toward the Chrysler. When he reached the driver’s window, he bent down and peered inside. Behind the wheel was a white male, mid-to late sixties, round face, big round-rimmed glasses, close-cropped gray hair. Seated next to him was a matronly woman, presumably his wife, looking slightly perturbed. Stampler immediately recognized the couple as Harry and Bess Truman. Until very recently they had been the president and first lady of the United States of America. Now they were in the custody of Trooper Manley Stampler. “Shit,” Stampler thought to himself. “What am I gonna do now?” Harry Truman was the last president to leave the White House and return to something resembling a normal life. And in the summer of 1953 he did something millions of ordinary Americans do all the time, but something no former president had ever done before—and none has done since. He took a road trip, unaccompanied by Secret Service agents, bodyguards, or attendants of any kind. Truman and his wife, Bess, drove from their home in Independence, Missouri, to the East Coast and back again. Harry was behind the wheel. Bess rode shotgun. The trip lasted nearly three weeks. One night they stayed in a cheap motel. Another night they crashed with friends. All along the way, they ate in roadside diners. Occasionally mobs would swarm them, beseeching Harry for an autograph or just a handshake. In towns where they were recognized, nervous local officials frantically arranged “escorts” to look after the famous couple. Sometimes, though, the former president and first lady went unrecognized. They were, in Harry’s words, just two “plain American citizens” taking a long car trip. Waitresses and service station attendants didn’t realize that the friendly, well-dressed older gentleman they were waiting on was, in fact, America’s thirty-third president (or thirty-second—Harry himself could never understand why Grover Cleveland was counted as two presidents). Everywhere they went, the Trumans crossed paths with ordinary Americans, from Manley Stampler to New York cabbies. But their trip also took them to the upper reaches of society in mid-twentieth-century America. In Washington, Harry had lunch with two young up-and-coming senators, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, and ran into the new vice president, Richard Nixon. Bess had tea with Woodrow Wilson’s widow. In New York, the couple took in the most popular shows on Broadway, and Harry appeared (albeit quite by accident) on a new television program called the Today show. It was a long, strange trip, and, after nearly eight hard years in the White House, Harry Truman loved every minute of it. As one newspaper put it, he was “carefree as a schoolboy in summer.” It would stand out as one of the most delightful and memorable experiences in his long and exceedingly eventful life. It was also an episode unique in the annals of the American presidency, and it helped shape the modern “ex-presidency,” which has become an institution in its own right. Today ex-presidents get retirement packages that can be worth more than a million dollars a year. When Harry Truman left the White House in 1953, his only income was a small army pension. He had no government-provided office space, staff, or security detail. Shortly before leaving office, he’d had to take out a loan from a Washington bank to help make ends meet. One of the reasons he and Bess drove themselves halfway across the country and back was that they couldn’t afford a more extravagant trip. Harry and Bess Truman’s road trip also marked the end of an era: never again would a former president and first lady mingle so casually with their fellow citizens. The story of their trip, then, is the story of life in America in 1953, a

Description: