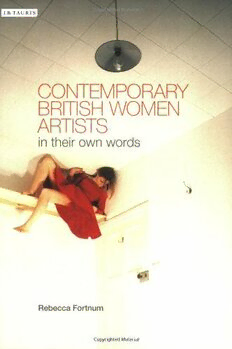

Contemporary British women artists : in their own words PDF

Preview Contemporary British women artists : in their own words

2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page i CONTEMPORARY BRITISH WOMEN ARTISTS In their own words REBECCA FORTNUM 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page ii Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road,London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue,New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States of America and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St.Martin’s Press,175 Fifth Avenue,New York NY 10010 Copyright © Rebecca Fortnum 2007 The right of Rebecca Fortnum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patent Act 1988. All rights reserved.Except for brief quotations in a review,this book,or any part thereof,may not be reproduced,stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,or transmitted,in any form or by any means,electronic,mechanical,photocopying,recording or otherwise,without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN:978 1 84511 224 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number:available Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd,Padstow,Cornwall Layout by FiSHBooks,Enfield,Middx. 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page iii CONTENTS Acknowledgments iv Introduction v Anya Gallaccio 1 Christine Borland 9 Jane Harris 17 Hayley Newman 25 Maria Lalic´ 33 Jananne Al-Ani 39 Gillian Ayres 47 Tracey Emin 55 Lucy Gunning 65 Jemima Stehli 73 Claire Barclay 81 Maria Chevska 87 Tacita Dean 95 Emma Kay 105 Sonia Boyce 113 Tania Kovats 121 Runa Islam 131 Vanessa Jackson 137 Tomoko Takahashi 145 Paula Rego 153 Artists’Biographies 161 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council,the Arts Council of England and the Research Committees of Wimbledon School of Art and Camberwell College of Art for their financial assistance in the making of this publication. I’d also like to thank Eve Fortnum, Beth Harland and Richard Elliott for all their help in so many ways, as well as Martyn Evans and Jacqueline Griffin for their professional expertise.Thanks also to Nicola Denny and Susan Lawson from I.B.Tauris. Finally, I would like to pay tribute to the dedication, integrity and insight of the artists whose words you will find in this book. Photo credits Photographs of Tacita Dean and Gillian Ayres by Richard Elliott Photograph of Tracey Emin by Johnnie Shand Kydd All other photographs of artists by Rebecca Fortnum Typographical design Gary Pearson,lomi-lomi.co.uk 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page v INTRODUCTION Something of the moment Rebecca Fortnum I think there are artistic truths that hit something of the moment of when they are made. GILLIAN AYRES This collection of interviews with British women artists captures a moment in time, to record how and why contemporary art gets made (1). In doing so it reveals the artists as individuals, articulating their experience of the world, contemplating their particular set of concerns.Often their integrity in doing so is overwhelming; a far cry from the charlatanism popularly associated with contemporary artists. Indeed, I feel these interviews confirm the existence of genuinely reflective art practice in the early twenty-first century. One aspect of this book that becomes rapidly apparent is that the artist is audience as well as maker.When Anya Gallaccio marvels over the ‘economy of gesture’in such different artists as Pina Bausch,Giotto and Vermeer,we quickly become aware of her finely honed ability to analyse an artwork’s qualities and how that clarity of thought is then directed unflinchingly at her own practice. Like many of the artists represented in this book, this evidence of creative intelligence is all the more exciting for being so seldom a topic of discussion.For the abstract painter Maria Lalic´, Beethoven’s Diabolli Variations provides an epiphany as she realises the potential of her own work’s form and structure.As a young artist,Hayley Newman hears John Cage for the first time and a whole world of possibilities for the future present themselves. Maria Chevska’s deep involvement with modernist literature generates new visual form, conversations with the texts she excavates. In reading these artists’ ruminations, one becomes aware of them engaging with other practices, present and past, in a very real way.Listening,looking and thinking;they sift art’s canons,finding works that will sustain them in their creative journeys. Another sense that emerges from these interviews is that of the material prac- tice of art. These artists live in their work. Painter Vanessa Jackson, eloquently borrowing from Heidegger,describes it as ‘set[ting] up a space that I can dwell in’. What I understand by this is that the potential for thought and contemplation offered by making a work of art is hard to find in other spheres of existence and 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page vi CONTEMPORARY BRITISH WOMEN ARTISTS requires total engagement. It exists in the complete technical and intellectual immersion in the materials and mechanics of making and can occur in any medium. This experience often eludes formal description, yet continually surfaces in these conversations.When Tacita Dean describes editing her film she confides,‘you see,I edit alone and I edit on film’.With this we form a sense of the intense, and perhaps necessarily solitary, decision making process. Runa Islam discusses how she felt making three film-based works from 1998 and says,‘naming the processes seemed impossible’.This to-ing and fro-ing between bewilderment and certainty,knowing and not knowing,is crucial to the creative process and is characteristic of this sense of living ina work.When Emma Kay gave up profes- sional singing,she realised that it was the ‘rigorous discipline’of daily exercising in the pursuit of perfection she would take with her into her text based ‘memory’ works.More traditionally,perhaps,painter Jane Harris marries the self sufficient and absorbing structures of geometry with her acute visual observations stem- ming from her art school training.Harris describes this balance of ‘external’and ‘internal’ references, saying, ‘it is to do with perception but there is a structure underlying it that has rules’.Her practice absorbs visual phenomena,relying on the integrity of its internal structures.This evidence must go some way to allay Clare Barclay’s concern about the ‘fracture between making and thinking’ in current contemporary art practice. In these practices, thinking and making happen concurrently and inform each other.Barclay goes on to assert: ‘I believe we mustn’t lose touch with the world through making and understanding how things come about’. The evidence,amongst these artists at least,is that this is far from the case. Barclay’s comment clearly reveals her belief that this sense of living inthe work includes an ethical dimension.These art practices do not require an ivory tower, but rather a window to look out on the world. The work may contain ethical judgements yet hold back from didacticism.Often a note of urgency permeates these artists’words.When Jemima Stehli talks about reaching a crossroads in her practice (‘I wanted to deal with the things which are really at stake’),it is clear that her ambition for her work is bound up with exploring issues important to her. Indeed, in different ways, for all these artists, the collision between ethics and experience is evident.For some,such as Christine Borland,this dimension forms the actual subject of the work.For others,like Lucy Gunning,it leaks out of the work’s structure. Some tackle ethical issues explicitly. Both Paula Rego and Tracey Emin have made work about abortion that draws attention to women’s real experience in contrast to the philosophical or legal perspectives of other public platforms.Tania Kovats’s Virgin in a Condomhas direct political implications yet emerged from a sustained dialogue around the notion of the Madonna ‘as a vi 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page vii INTRODUCTION site’and an awareness of the way the work’s meaning can shift in relation to its context. Indeed, it is only through this personal engagement with the material that the deep politics emerge.As Paula Rego says of her work: ‘The painting is a thing on its own, apart from you. …..When I’ve finished it’s telling me something.’ And of course it also tells others;the work mediates between its individual maker and the world, finding ways for both artist and audience to comprehend their surroundings.And there is something else.I believe that this desire to speak from experience about the world through an engaged material practice has the influence of feminism at its root. Griselda Pollock and Roszika Parker’s seminal Old Mistresses; Women, Art and Ideology and other important works of feminist art history produced in the eight- ies,informed generations of female visual artists,including most of the artists in this book.Issues to do with the personal,the body,the domestic,as well as the use of low status techniques or materials,became validated as a consequence of these feminist explorations.In these interviews I believe we witness the impact of this feminist consciousness on art practice,both directly and indirectly.For example, the important ‘feminist’artist Mary Kelly,who practised in the UK in the eight- ies, is cited by several of these artists as a key point of reference. The fact that none of the artists in this book define themselves as ‘feminist artists’ does not signal feminism’s failure;this would be to misunderstand its strength.Indeed,the triumph of feminism (within the visual arts at least) has been its ability to integrate the real issues affecting women into the language of contemporary art.Feminism is a fundamental tool in our understanding of the world.For these artists,feminist issues take the form of the debates around ethics,power,representation,knowl- edge,memory and narrative,which are integral to their work.For example,artists as different as Jananne Al-Ani, Jemima Stehli and Christine Borland all record the way their practices have responded to the established feminist dialogue around the (female) body as object.Today we can detect feminist scholarship in the UK in the writings and exhibitions of a broad range of women theorists, artists and curators (2). Much of this work looks carefully at the artworks produced by women artists in order to analyse how it can contribute to feminist debate.This is important;for too long we have policed ourselves as good and bad feminists,feminists in life but not in art,in a cul-de-sac of recriminations.Now it seems possible that we might engage seriously with feminist issues in relation to the exciting work being made and shown today by successful women artists,with- out requiring it to be a straightforward celebration or a direct critique. Sonia Boyce embraces her political positioning as an artist but has developed a specula- tive approach to her practice.She says: vii 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page viii CONTEMPORARY BRITISH WOMEN ARTISTS ‘Now I don’t need to adhere to a declaration of intent; a right and a wrong. Instead I say, let’s just see what this is and how it unfolds’. With this statement Boyce is not shunning her responsibilities,rather she is aware that the complexities of the ethical (and emotional) issues her artwork explores need particular and discursive forms to articulate them. However, we are also in debt to feminist art history for spelling out another crucial fact. Artists, even those with contemporary success, cannot expect an assured place in the history books. Indeed, the lives and thoughts of women artists through the ages have often been painstakingly reassembled by feminist scholars to whom we owe the knowledge of their practice.This leaves us with an understanding of the importance of writing women ‘in’ to the story for future generations. This book aims to mark an investment in the account of women artists in the early twenty-first century for posterity.The impact of feminism has been far reaching, but not quite enough to sweep away the status quo of centuries. Let’s look briefly at the situation for British women artists in 2006. Beck’s Futures,the excellent talent spotting competition held annually since 2000 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, is a handy barometer of the contemporary art scene in this country. Just over a third (3) of the artists nominated for the award have been female. This is not to say that the competition discriminates against women; rather I think this figure represents the state of play for professional women artists. Of Turner Prize nominations, another very visible marker in the careers of young British artists, 27 per cent have been female (and less than 10 per cent of the winners). However, if we compare the early years (1984–1996) with more recent times (1997–2005), the figures show a leap from 19 per cent to 41 per cent of women artists nominated. So it is into this arena that this book goes.We have vast progress in the status of women artists but not equality,yet.Perhaps it should also be noted that we hardly start from a level playing field. In this country the vast majority of professional artists have been to art school and these art schools,for the last ten years at least, are made up of disproportionately more female students. Lastly, a question remains in a book of this nature about the interviews themselves. What can artists contribute to the debate around their work? Recently, in my role as an academic researcher, I have initiated a project to document artists’processes (4).A more detailed knowledge of creative processes allows us to establish models for practice as research and this is proving useful in our current academic climate. But this is more than merely responding to contemporary academic demands.I believe that once we have acknowledged the fact that works of art can never be fully translated into words, a range of multivalent narratives quite happily attach themselves to visual production.And, whilst the artists are here, and willing to answer questions, we have the viii 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 2:18 pm Page ix INTRODUCTION opportunity to add their voices to any discussion about their work. If it is clear that they do not hold the ‘meaning’ of their work as a privileged author, then their accounts can often extend our thoughts about their own artworks, often creating additional levels of understanding. This chance only exists during the artist’s lifespan, after that we cannot predict with complete certainty how these words, or indeed the work, will be valued. Personally, I am grateful to the interviewers of the painter Alice Neel whose witty observations seemed to strike a chord at an early stage of my own practice. Indeed, my artist self is always interested in hearing other artists talk of their work.Rarely,if ever,have I been disappointed.Articulate or otherwise,the mysterious relationship of an artist to their work can never be exhausted and is compulsive listening, particularly for those that also try to make. I am all too aware that the current field of women artists practicing in the UK is vast and that I have selected only 20 artists from it.The artists were chosen to represent a cross section of practices from the UK’s art scene.You may detect bias, for which I can’t offer a defence – this is surely inevitable in such an endeavour. Bearing in mind that many of the readers of this volume will be artists themselves, often at an early stage in their career, I have often chosen to spend time tracing the paths of the artists’ development. Indeed, these artists provide a range of models for how creative practice can evolve.I admire all the artists in this book enormously and have found their reflections fascinating. I hope you will too. NOTES 1 Tacita Dean,Jane Harris and Tania Kovats interviews took place in 2001, Gillian Ayres,Maria Lalic,Maria Chevska,Vanessa Jackson in 2004 and all others in 2005. 2 I’m thinking,for example,of writing by Maria Walsh,Paula Smithard, Marsha Meskimmon or Rosemary Betterton or exhibitions such as Warped (Angel Row Gallery,2002),And the One Doesn’t Stir Without the Other(Ormeau Baths Gallery,2003),Unframed,(Standpoint Gallery,2004),Her Noise(South London Gallery,2005) or symposiums such as Mediated Pleasures in (post) Feminist Contexts,convened by Sue Tate and Clare Johnson at the University of West of England in 2005. 3 27 out of 73 nominated artists in Beck’s Futures (2000 – 2006) have been female.Interestingly,there has been an equal split between male and female winners.Since 2001 there have been 32 judges,12 of them female. 4 The Visual Intelligences Research Project,at the Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts,Lancaster University where I am currently Research Fellow. ix 2721 CC of Art. In Own Words. 19/9/06 4:01 pm Page x