Casanova the Irresistible PDF

Preview Casanova the Irresistible

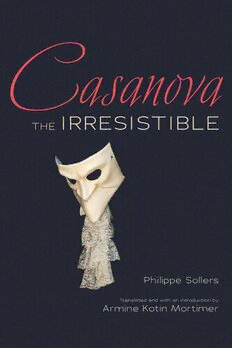

Ca sanova I r r e s I st I b l e the Philippe sollers translated and with an introduction by Armine Kotin Mortimer Casanova IrresIstIble the Ca sanova IrresIstIble the Philippe Sollers translated and with an Introduction by Armine Kotin Mortimer University of illinois Press Urbana, Chicago, and springfield Originally published as Casanova l’admirable by Éditions Plon, © 1998 Introduction and Translation © 2016 by Armine Kotin Mortimer All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America c 5 4 3 2 1 ∞ This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sollers, Philippe, 1936– author. | Mortimer, Armine Kotin, 1943– translator. Title: Casanova the irresistible / Philippe Sollers ; translated and with an introduction by Armine Kotin Mortimer. Other titles: Casanova l’admirable. English Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2016] | Translated from the French. | Includes index. Identifiers: lccn 2015047409 (print) | lccn 2015051355 (ebook) | isbn 9780252039980 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780252098154 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: Casanova, Giacomo, 1725–1798. | Adventure and adventurers—Europe—Biography. | Europe—Biography. Classification: lcc d285.8.c4 s6613 2016 (print) | lcc d285.8.c4 (ebook) | ddc 940.2/53092—dc23 lc record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015047409 Translator’s Introduction Armine Kotin Mortimer People think they know Casanova, but they are wrong, Philippe Sollers writes in the opening of this book. The man has become a myth, a circus animal, a mechanical lover, a more or less senile or ridiculous marionette. Let’s instead see what he really wrote about himself, says Sollers. His 1998 Casanova l’admirable stems from a fresh, idiosyncratic reading of the thousands of pages of Casanova’s memoirs, Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life), written in French between 1789 and 1798 and now published in twelve volumes. This remarkable work, the chief source of information about Casa- nova, has been subjected to abridgment and bowdlerizing as well as incom- plete and inaccurate translations, the objects of Sollers’s critique. He corrects these depredations by retelling the story and interweaving into it exposition, observations, analyses, and opinions of his own. His tactic is to seek the “truth,” and he directs his scorn at those biographical accounts that distort the story for their own purposes, mostly because of Casanova’s sensational descriptions of his relations with women. Serious Casanovists have shown that the writer fictionalizes only a little, and that the inevitable errors such as a memoirist might make are mostly minor. Sollers wants readers to know the plain realities of this crafty, cunning, colorful human being: “Let us rather conceive of him as he is: simple, direct, courageous, cultivated, seductive, funny. A philosopher in action.” Giacomo Casanova wrote his memoirs in a castle in Dux (now Duchcov) in Bohemia during a period of nine years at the end of his life. Their 4,545 manu- script pages are immensely detailed. Casanova made notes, kept documents, and wrote out events soon after they happened. He left these accumulating materials with friends or carried them with him everywhere—and he moved v vi around constantly, eventually ending up in Dux, where he was employed by Count Waldstein as a librarian for the last thirteen years of his life. The story he wrote can be compared to the excellent 1961 biography Casanova by James Rives Childs (1893–1987), who drew heavily on archival sources. Rives Childs’s augmented Casanova: A New Perspective, published in 1988, remains the most authoritative reference. Casanova was born in Venice to two actors. Raised by a grandmother, he was launched on his various careers (if they can be so called) in his mid-teens. Destined at first to the priesthood, he lacked the vocation; lawyering didn’t take, either. Throughout his life, in the absence of noble birth and secure finances, he used his wits and his chameleon qualities to fashion himself into whatever identity was needed. For instance, he sees a patrician collapse in a gondola: “Giacomo happens to be there, he takes charge, takes him back to his palace, prevents people from taking bad care of him, turns himself into a doctor, takes it seriously. Fortune guides him. ‘Now I have become the doctor of one of the most illustrious members of the Venetian Senate,’” he notes, and he is rewarded by being adopted. He had no fixed profession, and one might even say no fixed address. (The title of Ian Kelly’s recent Casanova: Actor, Lover, Priest, Spy is suggestive.) Though he was “homeless,” Venice remained home for him, the place to which he yearned to return during his years of wandering. But he spent very little time there and was in fact exiled from the Most Serene Republic more than once. No doubt that is why he has usually been called an “adventurer,” a description that covers all the activities in which Casanova engaged in the hope of sustaining himself: soldier, theater violinist, magician, alchemist, mathematician, doctor, matchmaker, assistant to various political entities, employee of the Inquisition, financier, manufacturer of silk fabrics, historian, gambler, and more—not to forget librarian at the end. He was curi- ous about everything and was constantly in motion. Love was of course Casanova’s chief pleasure in life. Sollers, however, is among those writers on his subject who object to a common image of the Story of My Life as the narrative of a repetitive, obsessive series of mechanical and superficial sex acts. Repetitive, yes, but neither mechanical nor superficial, nor truly obsessive. The Casanova experiment is scientific, Sollers wants to show, and as such gains by being repeated, because new insights accumulate with each event—and also because, in good scientific practice, an experiment should be repeatable. The actions of his body brought him knowledge about the nature of the human being; he behaved like a scientist who is curious to discover whatever he can about the world in which he finds himself. Such is the persona Sollers presents: a fearless experimenter with his body, even when it brought him pain instead of pleasure. vii Most important, and Sollers insists on this, Casanova was a writer. Besides his memoirs, he wrote books, pamphlets, and articles in three languages, including a multivolume science fiction novel. This focus on the writing may surprise readers who know that Sollers frequently writes about women and sexuality. Not just a great lover who took the experiences of his body as his primary subject, Casanova was a great writer who composed much as a musician might, as Sollers writes more than once, to achieve an ensemble greater than the sum of its parts or of its notes: “Casanova is a great composer. In life as in writing. His intent is to show that his life unfolded as if it were being written.” A great deal of Sollers’s admiration for this “irresistible” narrative rests on the fact that this Italian living in German-speaking Bohemia chose to write the story of his life in French. For Sollers, French is the revolutionary language, the language of freedom. People of the eighteenth century enjoyed a freedom that was, Sollers writes, so concentrated that they seem perpetually in advance of us. “Listen to Mozart—you will hear it right away. Same fresh air effect when we read Casanova.” The eighteenth century is alive for Sollers and exemplified by the key figures he writes about: Mozart, Vivant Denon (founder of the Louvre Museum), Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Denis Diderot (in a rarely seen video in which Sollers acts the part of this important Enlightenment intellectual). So vitally does he feel their qualities, it’s as if those men never died; so alive are they in his mind that the eighteenth century superimposes itself on the twenty-first. As a result, there comes a moment in Sollers’s writing about them when the eighteenth-century figures appear in his presence and blend with him: eventually, where Sollers himself is the earlier figure. Casanova the Irresistible is, it turns out, also about Sollers. It’s a textual strategy of self-identification, a way of stating his stance, similar to the unique way he has of writing about himself in his novels from 1983 on. In those novels, Sollers builds an image of a consistent narrator persona across multiple first-person characters with common characteristics: an omnipresent speaker, the focal point from which everything is seen; a writer of keen intelligence; and always a marginalized social critic—in sum, through all the “Multiple Related Identities,” an image of the author himself. In Sollers’s view of Casanova, those characteristics of the autobiographical persona are present in a more subtle, not to say surreptitious, way. This somewhat devious (though perfectly clear) substitution is most visible at the end of Casanova the Irresistible, where we will see “another” Casanova strolling around Venice on that key date of June 4, 1998, while all around him celebrations mark the fact that the city’s favorite son has been dead for two viii hundred years. “I wanted to speak about another Casa. The one who on this very day, in Venice, picks his way among the Japanese tourists near the Doge’s Palace. No one pays attention to him. Two hundred years after his death, he seems to be in excellent shape. Hale and hearty as when he was thirty, just before his arrest.” At this point, Sollers has entirely identified with Casanova; the superposition, the subtle substitution, are complete. But in style and man- ner, in artful undercurrents, the reader comes to recognize how the author has “updated” his subject throughout the essay as well. In the very manner of writing about Casanova, Sollers seeks to make him present among us as a model from which we should glean lessons unavailable from the majority of those who speak and write now. Sollers has said that he wrote this book to shame society for what it has repressed or neglected and for its failure to be cognizant of its failings. In it he affirms a philosophy of life stemming from Casanova’s admirable qualities. His reasons are thus quite personal as well as social. Casanova comments that his body and his soul are one: “I have never been able to conceive how a father can tenderly love his charming daughter without at least once having slept with her. This conceptual impotence has always convinced me, and still convinces me all the more strongly today, that my mind and my matter form a single substance.” Apart from the astonishing affirmation of father-daughter incest, the importance of this passage lies in the philosophy it expresses: the sameness of body and soul, or of mind and matter. Sollers proposes in Casanova “un homme heureux,” a happy man. Here was a man who had fun in life, motivated throughout by his desire to enjoy himself, simply put; the happiness of his soul was no different from the happiness of his body. Authors rarely deign to describe themselves as happy people, but Sollers affirms it for the one he calls Casa, and more importantly, through him, for himself. This attitude is typical of Philippe Sollers. He has always maintained his inde- pendence from any trend, critical fashion, style, or adherence. Born near Bor- deaux in 1936, Sollers made his brilliant entry onto the Parisian intellectual scene in 1958–1960 with back-to-back publications and the founding, with oth- ers, of the journal Tel Quel, destined to become the arbiter of French thought for the next two decades and the spearhead of what became known in the United States as “French theory.” A leading exponent of the avant-garde, Sollers wrote novels reputed as “difficult” and “experimental” during the sixties and seventies (Drame, translated as Event; Nombres; Lois; the two punctuation-less books H and Paradis, the last appearing in 1981 and 1986 after serial publication), then suddenly began writing novels in a “readable” style with the publication in 1983 of the brilliant Femmes, translated by Barbara Bray as Women. He continues ix to publish novels as well as book-length essays and extended interviews on many topics, in art, literature, music, photography, biography, and social his- tory. In addition to his tremendous written output, Sollers maintains a striking media presence as well as a blog and “Interventions” on his website, making him one of the most widely known authors in France. He lives in Paris with his wife, Julia Kristeva. In France, this man, often misunderstood by casual readers, is nevertheless a touchstone of intellectual life, a person of considerable erudition who has chosen to express himself via a verbal art unique to him. From his self-defined stance as a marginalized thinker on humanity’s behalf, he is a gadfly who pricks the conscience of his country. William Cloonan describes Sollers as a “public intellectual” considered on a par with Lacan, Barthes, and Foucault. Michel Braudeau calls Sollers a “remarkable critic, partisan of the Enlightenment and of happiness, love, and music, egocentric and very generous, the most agile runner on every sort of track, always the first to arrive.” “Happiness, love, and music” characterize all of Sollers’s writing, not unlike Casanova’s. This is especially evident in the novels written since the “turning point” of 1983, when Gallimard, the publisher Sollers called the “central bank,” brought out Femmes. That bestseller was followed by fifteen novels, among them Portrait du joueur, Le Cœur absolu, Le Lys d’or, La Fête à Venise, Le Secret, Passion fixe, L’Étoile des amants, Une vie divine, Trésor d’amour, Médium, and the 2015 L’École du mystère. His book-length essays include the autobiographical Un vrai roman: Mémoires and Portraits de femmes. Many of his books, includ- ing ones from before 1983, have been released in paperback editions, and a few of the novels have been translated into English. Among the nonfiction books, the most recent translation into English is Mysterious Mozart.