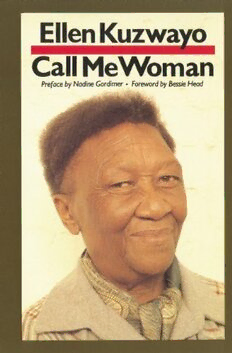

Call Me Woman PDF

Preview Call Me Woman

~ First published 1996 Ravan Press This edition published 2004 by Picador Africa an imprint of Pan Macmillan South Africa P.O. Box 411717, Craighall, johannesburg 2024 www.panmacmillan.co.za Reprinted 2005 ISBN 0 958 47082 0 © Copyright Ellen Kuzwayo 1985 © Preface Nadine Gordimer 1985 © Foreword Bessie Head 1985 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable for criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Typeset in 10 on 13pt Paiatino by PH Setting Cover design: Lionel McMurray Printed and bound in South Africa by CTP Book Printers Note on this edition In the re-publication of this work, the publishers have elected to retain the integrity of the original material. Thus subsequent events, including changes to place names, have not been chari.ged, and should be considered in the light of the time in which the author created this work. I dedicate this book to my loving mother Emma Mutsi Tsimatsima, formedy Merafe, borh Makgothi and to my sons Matshwene Everington Moloto, Bakone Justice Moloto, Ndabezitha Godfrey Kuzwayo and the Youth of my Community. Contents Acknowledgements ix Preface by Nadine Gordimer xi Foreword by Bessie Head xiii Ellen Kuzwayo' s Career xvi Principal legislation affecting the black community, and chronology of major events xix PART ONE Soweto 1 Coming Back Home 3 2 Hunger Knows No Laws 18 3 Violence in the Community 46 PART TWO My Road to Soweto 4 My Lost Birthright 63 5 Unfolding Horizons 87 6 Further Education and Growing Doubts 106 7 Physical and Emotional Shocks 112 8 Farewell Thaba'Nchu 123 9 A Home of My Own 135 10 Return to Johannesburg 153 11 Looking to the Young 169 12 Changing Roles in Mid-Stream 179 13 I See My Sons Grow Up 207 14 How the State Sees Me 227 PART THREE Patterns Behlnd the Struggle 15 Finding Our Strength 253 16 'Minors' Are Heroines 275 17 The Church and the Black Woman 287 18 Nkosi Sikelel' i Afrika-God Bless Africa 295 South African Black Women Medical Doctors 302 South African Black Women Lawyers 304 Acknowledgements My thanks to: The Maggie Magaba Trust and Zamani Soweto Sisters Council for their moral support and willingness to make their contribution when it was needed, and for their sisterhood. Harry Oppenheimer for making it possible for me to start writ ing this book- through the sponsorship he gave me. John and Jane Moores for their sponsorship to complete the book, their warm friendship and generous family hospitality. Elizabeth Wolpert, for her continued encouragement and moral support and for her patience to listen with a critical ear to my work; and both her and her family for providing their home as a base to work from during my stay in England, and where I met many old and new friends from all over the world. My sons and their families for their deep understanding and acceptance of all my efforts and commitments. Nadine Gordimer for accepting my first request to assess my work and her encouragement: 'Ellen I am pleasantly surprised by what you have written-go ahead and allow no one to interfere in your style of work!' Bessie Head for graciously dropping everything to meet me at very short notice when I was passing through Serowe. Ros de Lanerolle and The Women's Press team for accepting to publish my book on first request, and their tremendous support, guidance and patience. Marsaili Cameron, my editor, whose sensitivity and under standing helped me through the process of writing this book. Robin Lee for his professional contribution and support at the beginning when I struggled to see my direction. The University of the Witwatersrand for giving me free office space to write the book. The Universities of Fort Hare, Natal, Ngoya and the Witwatersrand for their cooperation in supplying me with research material. I want to thank all the people I interviewed for their coopera tion and willingness to work with me at all times. All my sisters in exile. I am so aware of their painful separation from their families and country. Last but by no means least - Dorcas Kepi Ramphomane, my personal secretary. For her commitment, support and understand ing - particularly at the moment when I was under pressure against time and production of work. X Preface Nadine Gordimer ELLEN KUZWAYO IS HISTORY in the person of one woman. Fortunately, although she is not a writer, she has the memory and the gift of unselfconscious expression that enable her to tell her story as no-one else could. It is a story that will be both exotically revealing and revealing ly familiar to readers. Ellen Kuzwayo' s life has been lived as a black woman in South Africa, with all this implies. But it is also the life of that generation of women anywhere-in different epochs in different countries-who have moved from the traditional place in home and family system to an industrialised world in which they had to fight to make a place for themselves. Perhaps the most striking aspect of this book is the least obvious. It is an intimate account of the psychological road from the old, stable, nineteenth century African equivalent of a country squire's home to the black proletarian dormitories of Johannesburg. Living through this, Ellen Kuzwayo emerges not only as a brave and life-affirming person; she represents in addition a particular triumph: wholeness attained by the transitional woman. In her personal attitudes, her innate fastidiousness, her social ease, she seems one of the last of the old African upper-class-Christianised, at home in European culture but not yet robbed of land and pre-conquest African culture. Yet in her break with the traditional circumscription of a married woman's life, her braving of her society's disapproval of divorce and finally her move to the city, she cast away all props. Not only did she learn to stand alone and define herself anew in response to the terrible pressures of a city ghetto; she did so without killing within herself the African woman that she was. Ellen Kuzwayo is not Westernised; she is one of those who have Africanised the Western concept of woman and in herself achieved a synthesis with meaning for all who experience cultur al conflict. xi That this conflict, in her case, was rawly exacerbated by racist laws in South Africa is self-evident. Yet Ellen Kuzwayo' s evolution as a politically active woman, all the way to the final commitment to the black struggle that brought her to prison, is shown to stem from the same instinct to turn toward freedom-and pay the price -that enabled her to become a whole and independent being as a woman. It all began that night she spent sleeping in a graveyard in escape from the tyranny of a bad marriage; from that graveyard she was reborn, as a woman and as a black person. Her simple but highly observant nanative brings statistics alive. What it means to be black in segregated Johannesburg is conveyed concretely, as if one absorbed it for oneself in a Soweto street. Whether she is doughtily defending the black women whom eco nomic necessity makes into illicit liquor sellers, or explaining the economics of the women potters of her childhood who bartered the vessel for the amount of grain it would hold, her approach is fresh and vivid. And her total honesty is very moving. She is not afraid to reveal an aspect of racism not often admitted by its vic tims: the moral ambiguity oppression brings. In a touching self examination she confesses that the conditions of black ghetto life have changed her strong moral convictions about crime. We in turn have to ask ourselves what kind of society brings a woman of this one's strict integrity to say 'I am shocked that as I become older . . . I find that my attitude has been changing. Now, when I read in the press about the theft of thousands of rands by blacks ... I often express the desire that they are not ills covered.' We are shocked, too: not by Ellen Kuzwayo, who 'would never (herself) take anyone's belongings', but by South Africa. This book is true testimony from a wonderful woman. For myself, she is one of those people who give me faith in the new and different South Africa they will create. Nadine Gordimer June 1984 xii