Beyond born again : toward evangelical maturity PDF

Preview Beyond born again : toward evangelical maturity

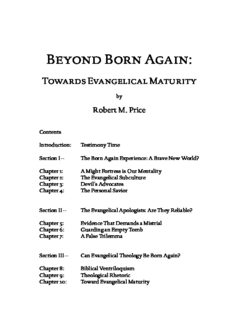

Beyond Born Again: Towards Evangelical Maturity by Robert M. Price Contents Introduction: Testimony Time Section I-- The Born Again Experience: A Brave New World? Chapter 1: A Might Fortress is Our Mentality Chapter 2: The Evangelical Subculture Chapter 3: Devil's Advocates Chapter 4: The Personal Savior Section II-- The Evangelical Apologists: Are They Reliable? Chapter 5: Evidence That Demands a Mistrial Chapter 6: Guarding an Empty Tomb Chapter 7: A False Trilemma Section III-- Can Evangelical Theology Be Born Again? Chapter 8: Biblical Ventriloquism Chapter 9: Theological Rhetoric Chapter 10: Toward Evangelical Maturity Appendix-- Getting a New Start (1993) Introduction: Testimony Time "Wishes and hopes can also mature with men. They can lose their infantile form... and their youthful enthusiasm without being given up." -- Jürgen Moltmann, The Crucified God "I know you better now And I don't fall for all your tricks And you've lost the one advantage of my youth." -- Larry Norman, "The Great American Novel" "When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; But when I became a man, I put away childish things." -- The Apostle Paul, I Corinthians 13:11 By now, most people have heard of "Born Again Christians." The recent media prominence of these interesting people was, of course, sparked by Jimmy Carter's "testimony" that he had been "born again." Reactions to the new visibility were of at least two types: one can still spot bumper stickers sporting either "I found it" or "I lost it" slogans. Some applaud the new "Evangelical renaissance." Others are uneasy because of the political repression they fear (cf. Malcolm Boyd's prediction of a "demagogic, chauvinistic national religious movement.... 'Do you accept Jesus Christ as your personal Lord and Savior?' would be the inquisitorial question asked.") [1] Still others doubt that there has been any revival at all, only increased visibility, or the faddishness of the phrase "born again." But however one feels about Born Again Christians, one should at least know who they are and what they stand for. In response to this need, we have witnessed a flood of books analyzing Evangelicals and their "old-time religion." Most have been written by Evangelical Christians themselves (e.g., Donald Bloesch, The Evangelical Renaissance; David Wells and John Woodbridge, The Evangelicals, Richard Quebedeaux, The Young Evangelicals and The Worldly Evangelicals; Morris Inch, The Evangelical Challenge), but a few have been written by non- or ex-Evangelicals (e.g., James Barr, Fundamentalism). Of which kind is the book you now hold in your hands? It's hard to say.... If you are familiar with Tillich's phrase "on the boundary," perhaps you will understand my reticence to jump into a category. But here, what do such categories mean? For even an "ex-Evangelical" is often merely one more kind of Evangelical with one of several available prefixes. For instance, have you ever seen a "Liberal" religion professor give a hard time to fundamentalist students in his class? Often the most militant of such professors were once fundamentalists themselves and are now trying to settle a score. They have in fact become Liberal fundamentalists! Let me share briefly with you my background in the Evangelical Christian scene. Every writer is working from a biographical context, and it's only fair that the reader be told what it is. This is especially true on a subject as ticklish as ours. Well, I was converted as an adolescent in a Conservative Baptist Church. Having Jesus Christ as my personal savior gave me "eternal security" from the flames of hell which I otherwise had to fear. During the next few years I absorbed much biblical teaching through the filter of dispensationalist fundamentalism. I learned to pray and read scripture, and to "witness" to my friends (and to feel pretty guilty if I didn't do these things). An acknowledged "spiritual leader" among the youth membership, I found the peer-acceptance that all teenagers so desperately need. Church activities weren't enough, so I joined a student group called "HiBA" (or "High School Born- Againers") in order to see as many as possible of my classmates "come to the Lord." Eventually, several did. Just think, I was a father (spiritually at least) several times by age seventeen! My Campus Crusade for Christ training in evangelism served me in good stead. Of course, winning others to Christ was only half the problem. ________________________________________ 2 After all, I could only help my converts to mature spiritually as much as I myself had. I must be a true man of God. Reading devotional works such as Robert Boyd Munger's My Heart, Christ's Home, Miles Stanford's Principles of Spiritual Growth, and even C. S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters considerably advanced my progress in piety. But never had I found so much spiritual wisdom as in Bill Gothard's "Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts," a week-long seminar on God's (and Gothard's) unbeatable principles for a successful Christian life. I took this amassed lore with me when I went to college. It did not take me long to become a leader in the campus chapter of Inter Varsity Christian Fellowship. My knowledge of biblical doctrine and evangelistic technique was welcome here. As I encountered new influences (though not too many, sheltered as I was), my Christian life grew in new ways. As I erected new barriers, I began to let down some old ones. One the one hand, there were all of those "unsaved professors." One should avoid religion courses offered by such people. Who knows what disturbing things one might hear? But eventually I was ready for combat on this enemy turf. I had become interested in "apologetics," the science of defending the faith. Mentally, I stocked up on the writings of such knights of the truth as Francis Schaeffer, F. F. Bruce, John Warwick Montgomery, and Os Guiness. Ready to do battle, I'm sure I irritated my professors no little. In a battle like this, one must close ranks with the like-minded. Within the circle of Inter Varsity, I soon encountered new varieties of Evangelical belief and lifestyle. I learned to tolerate and even welcome different ideas on eschatology, worldliness, etc. Wider horizons were a pleasant discovery. Eventually, I had become a convinced and enthusiastic "neo-Evangelical," going to movies (after the long cinematic abstinence of my teenage fundamentalist period), qualifying biblical inerrancy, and teaching the Bible in a Catholic Charismatic prayer group. My commitment to Jesus Christ gave me an exciting and satisfying sense of purpose. The Bible was a thing of constant fascination, and I learned to exult in the love of Jesus, and of my brothers and sisters. During my college years, I read voraciously, becoming familiar with "our" (Evangelical) literature on most subjects. Not satisfied with encountering the writers only through their works, I took several opportunities to visit other cities where I sought out and conversed with various Evangelical leaders. In Wheaton, I met Carl F. H. Henry, Merrill Tenney, C. Peter Wagner, and Billy Melvin, President of the National Association of Evangelicals. At a conference in Ohio, I met my favorite inspirational writer Peter Gillquist. On a trip to Berkeley I stayed with the Christian World Liberation Front (now the Berkeley Christian Coalition), talking with Sharon Gallagher and Jack Sparks (now of the Evangelical Orthodox Church). In Chicago, I met David F. Wells and Donald Dayton. I talked with Dave Jackson of Reba Place Fellowship and Jim Wallis of the Post-American (now Sojourners). I discussed ministry and theology with these fascinating people and finally decided to go on to seminary. I chose Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, specializing in New Testament. This way, I felt I could prepare for a teaching ministry in my own way by concentrated biblical study. Also, I could continue ________________________________________ 3 my apologetical attack on Liberal, unbelieving biblical criticism and theology. Though I didn't have definite plans for the future (being confident of God's eventual guidance), what eventually happened still surprised me. One often hears the paradoxical statement that many enthusiastic students lose their faith while in seminary. As the story goes, the wide-eyed seminarian finds his faith in the Bible undermined by the destructive biblical criticism of his Liberal professors. Let me say that there is very little chance of this happening to anyone at my alma mater, where the commitment to Evangelical thought and practice is unswerving. My experience does not therefore fit the stereotype I have just described, but I did undergo quite a change. I found to my unpleasant surprise that by my second year, I was unable to affirm much of that upon which I had spent my life up to that point. I might add that I was dragged to this conclusion kicking and screaming. As I have said, one of my greatest interests was in apologetics, which in turn greatly contributed to my interest in New Testament studies. The reading of stalwarts like John Warwick Montgomery and Francis Schaeffer convinced me that the stakes indeed were high: if Evangelical Christianity were not true, and based upon historically true events, why then life really held no significance at all! This put me in quite a charged situation. On the one hand, it all must be true! Yet, on the other, I must be honest-- I could not try to convince an unbeliever with an apologetical argument I would not myself accept. My enthusiasm for the true faith, and the secret fear that the faith might not be true, were sources of fuel that fed each other. My zeal was great, but it was interrupted by periods of doubt that might last for months. The more terrible the doubt, the more zeal was needed to make up for it. As the zeal grew greater, the stakes became higher, and the fear in turn grew deeper. Naturally, I was reluctant to find any weakness in the various arguments in favor of the resurrection of Christ, or the historicity of the gospels, etc. Yet if there were weaknesses, I had to know! Eventually, I believe, I found them in the course of my own research. At the same time, my suspicions were beginning to mount concerning the viability of the way I had been told to interpret experience. I encountered personal disappointments which I piously assumed God must have sent "for a purpose." Praise the Lord, I figured. Still, I couldn't help but notice that I didn't need "God's will" as an explanatory factor. Human failure and immaturity seemed adequate explanations. Besides, what did it imply about life if every significant experience was significant only as a "test" sent by God? And could you be sure you had discerned God's will, since the last time you thought you had it, everything fizzled anyway? I began to wonder if my picture of life was adequate for the increasingly ambiguous world I lived in. Born- again living seemed to me just a crutch which no longer facilitated healing and growth, but actually protracted immaturity. During this period, I did not let my doubts and dissatisfactions stop me from sharing the good news of Jesus Christ. But evangelism began to present difficulties of its own. One cold night in Beverly, Massachusetts, I trudged out with a handful of other seminarians to "witness" to local sinners. As I sat conspicuously in a ________________________________________ 4 tavern telling a stranger about the abundant life Christ offered her, I suddenly found myself at a loss for words. Behind my evangelistic rhetoric, what did it all mean? Just how would her life change if she "accepted Christ"? Well, she would begin to seek guidance daily in God's Word, and to go to church, and... uh... well, basically, to take up new religious habits, I guess. This girl already believed in being kind, loving and honest. She didn't need religion for that. What did she need it for, I had to ask myself? Her "problem" seemed to be mainly that she didn't know the requisite passwords and shibboleths: "Christ is my personal savior," "I'm born again." Around the same time, I found myself in a Cambridge cafe having supper with some friends. We were on our way to a lecture by Harvey Cox, whose books I'd always found fascinating, though I'd filled their margins with vociferous criticisms. I suddenly thought, "Listen, is there really that much difference 'them' and 'us'?" I had always accepted the qualitative difference between the "saved" and the "unsaved." Until that moment, it was as if I and my fellow- seminarians had been sitting in a "no-damnation" section of an otherwise "unsaved" restaurant. Then, in a flash, we were all just people. My feeling about evangelism has never been quite the same. I had to reevaluate my faith. I had some idea of what other theological options were like. But since I had always read them only to refute them, it was going to take some adjustment to be able to give them a sympathetic hearing. In the summer of 1977, I took course work at Princeton Theological Seminary, learning much from Donald Juel and visiting professor Monica Hellwig. The next fall, I went to Boston University School of Theology and Harvard Divinity School (members of the Boston area consortium to which I had access as a Gordon-Conwell student). There I had the privilege of taking courses with Howard Clark Kee, Helmut Koester, and Harvey Cox. A new world had opened up to me, both theologically and personally. I felt like a college freshman, thinking through important questions for the first time. The anxiety of doubt had passed into the adventure of discovery. It was like being born again. This sharing of my "testimony" brings me now to the theme of the present book. One might call it an attempt to "put away childish things." Of course, I allude to Paul's eschatological vision in 1 Corinthians 13. The imperfect must fade with the advent of the perfect. Childish things, adequate in their day, must be set aside, perhaps painfully, when maturity knocks. My experiences and researches lead me to believe that there is a new maturity on the horizon, beckoning to Evangelical Christians. The current, tiring struggle over biblical inerrancy are part of the "birth pangs" of this "new age." In this book I will sketch several of the difficulties to be found in traditional Evangelical approaches. I will go on to outline some possible directions for the future already becoming apparent in the thinking of Evangelicals here and there. What I will be proposing is a really new Evangelicalism, something transcending Harold J. Ockenga's "Neo-Evangelicalism" (fundamentalism with better manners) and Richard Quebedeaux's "Young Evangelicalism" (politically and behaviorally liberalized Neo- Evangelicals). Let it be ________________________________________ 5