Before, during and after PPG 16 p4 The changing role of the local authority archaeologist PDF

Preview Before, during and after PPG 16 p4 The changing role of the local authority archaeologist

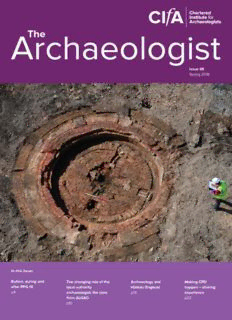

The Archaeologist Issue 98 Spring 2016 In this issue: Before, during and The changing role of the Archaeology and Making CPD after PPG 16 local authority Historic England happen –sharing p4 archaeologist: the view p13 experience from ALGAO p22 p10 Celebrating over 30 years at the forefront of Archaeological Geophysics Utility Detection & Mapping Topographic Geophysical Measured Building Railway & Pipeline Archaeological Laser Scanning Setting Out Boundary Disputes 01274 352066 As Built Records UXO Detection Void Detection SUMO Group Member CCTV Statutory Plan Collation www.gsbprospection.com [email protected] call :01684 592266 web : www.stratascanSUMO.com If your business is in archaeology make it your business to be in the CIfA Yearbook and Directory Contact Cathedral Communications for more information 01747 871717 Spring 2016 ⎥ Issue 98 Contents Notes for contributors 2 Editorial Themes and deadlines 4 Before, during and after: life pre-PPG 16, its impact after 1990, and the current TA99:will celebrate the depth and breadth of the struggle to retain its legacy Stuart Bryant and Jan Wills many types of work that archaeologists do in museums. We are looking for short case studies 9 Pre-Construct Archaeology: a child of PPG 16 Gary Brown about research projects, new approaches to display/interpretation, the outcomes of education, training and volunteer activities, or an account of 10 The changing role of the local authority archaeologist: the view from ALGAO the changing role of a curator and the challenges Quinton Carroll they face today. For further information, see the 'Noticeboard'. 12 What’s been going on? Archaeological investigations in England since 1990 Deadline for abstracts and images: 1 August Timothy Darvill TA100: Are you helping to deliver the aims and objectives set out within Scotland’s Archaeology 13 Archaeology and Historic England Steve Trow Strategy? We are looking for ideas, examples and opinions – how best to deliver a Scotland where 16 CIfA, advocacy and local authority services: 25 years on from PPG 16 Rob Lennox archaeology is for everyone? Deadline for abstracts and images: 1 December 19 Examples of PPG 16 sites across the UK 20 Assessing the value of community-generated historic environment research Dan Miles Contributions to The Archaeologistare encouraged. Please get in touch if you would like to discuss 22 Making CPD happen –sharing experience Andrea Smith ideas for articles, opinion pieces or interviews. We now invite submission of 100–150 word 24 Registered Organisation News abstracts for articles on the theme of forthcoming issues. Abstracts must be accompanied by at least 26 Registered Organisation Spotlight three hi-resolution images (at least 300dpi) in jpeg or tiff format, along with the appropriate photo 28 Member News captions and credits for each image listed within the text document. The editorial team will get in touch 31 Annual review of allegations of misconduct made against members and Registered regarding selection and final submissions. Organisations Alex Llewellyn We request that all authors pay close attention to CIfA house style guidance, which can be found on 32 Noticeboard the website: www.archaeologists.net/publications/ notesforauthors TAis made digitally available through the CIfA website and if this raises copyright issues for any authors, artists or photographers, please notify the editor. Copyright of content and illustrations remain with the author, and that of final design with CIfA. Authors are responsible for obtaining reproduction rights and for providing the editor with appropriate image captions and credits. Opinions expressed in The Archaeologistare those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIfA. Commisioning editorAlex Llewelllyn [email protected] Copy editorTess Millar Members’ news: please send to Lianne Birney, [email protected] Registered Organisations: please send to Jen Wooding, [email protected] CIfA, Miller Building, University of Reading Reading, RG6 6AB Cover photo: ULAS investigating the base of ceramic Design and layout by Sue Cawood kilns in Warwickshire, in advance of housing development. Printed by Fuller Davies Credit: Adam Stanford, Aerial-Cam The Archaeologist⎥1 Issue 98⎥ Spring 2016 EDITORIAL Roger M Thomas MCIfA (255) Publication produced by Historic England to mark the 25th anniversary of PPG 16. Available to download from Historic England website (https://historicengland.org.uk/). Cover photo credit: MOLA. in our home nations: a clear place for archaeology in the land-use planning process and a ‘polluter pays’ principle, under which the developer – not the state – is p4 responsible for dealing with the impacts of a development. In this, PPG 16 was reflecting wider trends in environmental protection, and also the terms of the Council of Europe’s Valletta Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage, published in 1992 (PPG 16 was developed in parallel with the Convention, with some of PPG 16’s authors also involved in drafting the Convention). The contributions in the following pages Major anniversaries encourage both reflect a range of perspectives. Jan Wills and p10 retrospection and looking ahead. November Stewart Bryant, both former local government 2015 saw the 25th anniversary of the archaeologists, review how archaeology in publication of Planning Policy Guidance note England developed between 1950 and the 16on Archaeology and Planning– almost present, and look ahead at what the future universally known as ‘PPG 16’. PPG 16 was a may hold (some of it very worrying). Gary slim document: its main text consists of only Brown of Pre-Construct Archaeology shows 31 paragraphs, occupying less than seven how the policy allowed new, commercial, pages. Relative to its size, though, PPG 16 archaeological organisations to develop, and had the most profound impact of any Quinton Carroll outlines its effect on local archaeological publication ever produced in government archaeology. Tim Darvill explains England. It generated a huge (more than ten- how theArchaeological investigations fold) increase in resources for archaeology, project (Bournemouth University and Historic p16 created a new industry, shaped the England) tracked the patterns of PPG 16- archaeological profession as we know it based work from 1990 to 2010. Steve Trow today, and produced extraordinary quantities looks at the archaeological role of Historic of new information and knowledge about the England, against the background of the past throughout the country. This issue of change in 1990 from a state-funded to a The Archaeologistmarks this anniversary by developer-funded system of archaeological bringing together contributions which look work. Rob Lennox draws attention to the back to the world as it was pre-1990 and at current severe pressures on the system of what happened after, but which also reflect local authority archaeological advice, and on what may lie ahead. describes CIfA’s advocacy work on this topic. We also include a small selection of Of course, CIfA is a UK-wide body, whereas vignettes, provided by a range of p22 the letter of PPG 16 only applied in England. archaeological organisations, of some Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland significant development-led archaeological produced their own equivalents between discoveries. This is important. In the end, we 1994 and 1999; the twentieth anniversary of do archaeology because it is interesting, and Scotland’s ‘NPPG 5’ in 2014 was celebrated these discoveries remind us of this; it is in TA91. There was naturally a great deal in surprisingly easy to lose sight of the point in common between the approaches adopted the busy-ness of our working lives. 2⎥The Archaeologist Spring 2016 ⎥ Issue 98 25 years PPG 16 of Any practising archaeologist under the age of about 40 will probably have little direct knowledge of how things were before 1990. Whatever the weaknesses of the present system, and the threats facing it, there is absolutely no doubt that we are in a hugely better position now than we were in the 1980s (let alone the 1960s and 1970s). Even in the 1980s, important sites could be lost without record through lack of evaluation, or through lack of state funds to pay for rescue excavation. So, if we look back, we have much to be thankful for. And what of the future? What might PPG 16 led to major investigations in development-led archaeology look like in previously unexplored areas. Excavations Without PPG 16, many extraordinary objects another 25 years’ time? The picture is mixed. beside the A1, North Yorkshire, 2014. would have been lost. Medieval devotional Funding pressures on central and local Credit: Dave MacLeod. © Historic England. panel, London. Credit: Andy Chopping/MOLA government bodies seem unlikely to abate Image number 28535_025 for some years, at best, and changes to the planning system pose serious challenges. Against these rather gloomy prognoses, one can also see some potential grounds for optimism. We have a very skilled and capable archaeological sector. Digital technologies offer scope for innovation in our recording methods, and for sharing information in ways that are much more ‘seamless’ than at present. Major university- based synthesis projects are proving beyond doubt the scope for development-led results to transform understanding of England’s human past. The value of the historic environment, including archaeological remains, for contributing to place-making and PPG 16 resulted in the growth of a strong archaeological profession. Excavations at Ysgol Bro quality of life is increasingly recognised. Dinefwr on behalf of Carmarthenshire County Council in 2014/15, by AB Heritage with Rubicon Perhaps the biggest challenge we face is that Heritage. Credit: AB Heritage Ltd/Rubicon Heritage Services Ltd of making sure that ‘development-led’ archaeology remains vibrant and exciting, both for us as professionals and for the wider public who, in one way or another, are paying for it. The solutions to that important challenge lie in our own hands. Roger M Thomas MCIfA (255 ) We can, then, look back with satisfaction on Roger is a member of the Historic what we have achieved since 1990, Environment Intelligence Team at Historic recognise that no system is perfect and that England. He led the production of Historic there are always areas for improvement, and England’s Building the Future, Transforming look forward with anticipation to what the our Pastpublication, launched in November next 25 years will hold for us. 2015 to mark the 25th anniversary of PPG 16. The Archaeologist⎥3 Issue 98⎥ Spring 2016 Before, during and Before: 1950–1975 The years between about 1950 and 1975 saw enormous expansion in after: life pre-PPG 16, housing, industry and infrastructure. The impact of all this on archaeology provoked widespread concern, leading to the formation its impact after 1990, of Rescue, the publication of many studies on the archaeological implications of development – especially in urban areas – and pressure on government to address both the lack of funding and the and the current organisational capacity to respond. For most of this period, responses relied heavily on voluntary efforts and on tolerant developers allowing struggle to retain its access to sites in advance of the commencement of work. Prior to 1981, when the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 came into force, even scheduled monuments had only limited legacy protection from damaging activities. Many known sites were destroyed without record. From what we now know about the density of archaeological sites in the English landscape, an even greater number of unknown ones must have suffered the same fate. Stewart Bryant MCIfA (83) and Jan Wills MCIfA (188) PPG 16 articulated the importance and the vulnerability of archaeological evidence, setting out a simple process for assessing the impact of proposed development and securing the preservation or recording of the archaeological remains affected depending on their significance. (above, left) (above) Worcester Emergency recording medieval city wall in Worcester City, during the ring road 1960s. Credit: Thanks construction, 1970s. to the late Phil Barker Credit: Jan Wills 4⎥The Archaeologist Spring 2016 ⎥ Issue 98 Local authority services had continued to expand, often proactively supported and part-funded by the DoE, so that by 1980 there were county archaeologists and SMRs in almost all counties in England, although full national coverage was not achieved until 1989. Pre-1990, only a very small proportion of developments (invariably where archaeology was already known to be an issue) had provision for any investigation other than unfunded ‘watching briefs’. This included many major developments: most notably the M25, the largest single infrastructure project of the 1980s and carried out with very limited archaeological recording. During: PPG 16 and its impact PPG 16 had a long gestation, but its eventual publication in 1990 was Jan drawing Anglo-Saxon wooden buildings prompted by a number of archaeology and development causes in Durham, early 1970s. Credit: Jan Wills célèbres, culminating in the discovery of the remains of Shakespeare’s Rose Theatre in London and the subsequent campaign to save it. This caused much political embarrassment, and government was finally persuaded that archaeological considerations needed to be properly Encouraged by a far-sighted government circular of 1972 (focused on integrated into the planning system in order to avoid similar difficulties threats to rural archaeological sites), some local authorities began in future. appointing staff (often museum-based) to address these issues. Embryonic Sites and Monuments Records (SMRs) were established, but coverage was patchy and funding limited. In 1974 the Department of the Environment (DoE)announced the establishment of 13 new regional archaeological advisory committees, led by a national committee, to advise on priorities for excavation, with a budget of just over £1 million. Following this initiative, the mix of local authorities, new committees and ‘units’ sought to respond to threats to archaeology through annual bids to the ‘rescue archaeology budget’ for excavations in advance of development. There was never enough money, and funding for post-excavation was almost always squeezed. Before: the 1980s The DoE’s rescue archaeology budget was supplemented in the 1980s by funding from various government job-creation schemes that supplied large numbers of workers for excavations – but not necessarily skilled people. The best of these projects were good and launched a number of archaeological careers; the worst left behind a trail of unpublished material. The 1980s also saw the beginning of developer funding, but it was wholly voluntary and almost entirely a London phenomenon; developers in other parts of the country were more often persuaded to supply some support in kind rather than cash. Although it had now been established that archaeology was a material consideration in the planning process, there was no clear basis in policy for the identification and recording of archaeological sites affected by development. The term ‘evaluation’ had begun to enter the archaeological lexicon, but the concepts of pre-determination and phased programmes of evaluation to characterise the archaeology and assess the impact of development were not used before the late 1980s. Nor was it easy through the planning process to secure mitigation. Where planning conditions were used it was mainly to secure unfunded watching briefs, although PPG 16-style ‘Grampian’ conditions were pioneered, and some more ambitious attempts were made to use voluntary Section 52 (now Section 106) planning agreements to secure archaeological recording. Machining, early 1980s style. Credit: Jan Wills The Archaeologist⎥5 Issue 98⎥ Spring 2016 Cirencester urban deposits. Credit: Gloucestershire County Council PPG 16 articulated the importance and the vulnerability of archaeological evidence... Existing patchy, voluntary and discretionary arrangements for dealing The immediate impact of PPG 16 was variable across England. with archaeology viathe planning process were now replaced by a Professional practice evolved slowly across the decade that mainstream responsibility for all planning authorities. PPG 16 articulated followed, there being little formal advice or guidance on the importance and the vulnerability of archaeological evidence, setting implementation until this was developed by the profession’s own out a simple process for assessing the impact of proposed development organisations such as the Association of County Archaeological and securing the preservation or recording of the archaeological remains Officers (later the Association of Local Government Archaeological affected depending on their significance. Responsibility for funding this Officers), the then Institute of Field Archaeologists, and the Standing work fell on the developer (Bryant and Thomas 2015, 9–10, provides a Conference of Archaeological Unit Managers (now the Federation of more detailed summary of PPG 16’s provisions1). Archaeological Managers and Employers). There were also significant cultural and institutional barriers to change amongst planners, The seemingly simple and logical processes introduced by PPG 16 developers and archaeologists, especially in the large parts of the were to have a profound impact on the structure of the archaeology country that had little or no prior experience of planning-based sector, would to lead to a dramatic increase in its size and also archaeology. fundamentally affect the nature of the power relations within it, as well as transforming understanding of the extent and complexity of After 1984, English Heritage continued the previous DoE support for archaeological evidence within the English landscape. local authority services, helping to fund the appointment of SMR officers and archaeological planning advisors if these did not yet exist. The requirement for developers to fund the costs of evaluation, This recognised the crucial curatorial role of providing advice within excavation and post-excavation led to the exercise of choice over the the planning system: advice that determined archaeological planning provider, and to the subsequent growth of a private sector of policy at a local level, initiated the process of establishing the archaeological consultants and contractors with budgets that far archaeological implications of individual development proposals and exceeded the previous levels of state funding. In addition, a clear followed this through by specifying what archaeological work was separation was found to be necessary between the organisation needed and monitoring it. requiring the archaeological work to be carried out (the local planning authority advised by a county or district archaeologist) and the By 2000, the planning system, through the application of PPG 16, had organisation that undertook the work on behalf of the developer (the become by far the most important means of managing change contracting field unit). Developers naturally looked to minimise their affecting the 90 per cent of the archaeological resource that is not costs and used the then highly controversial process of competitive designated. In parallel, after the end of English Heritage’s Monuments tendering as a means of doing so. Thus began the splitting of the Protection Programme in about 2000, very few archaeological sites profession into parallel strands of public/private, curatorial/contracting were scheduled, there being some consensus that management via – a structure that persists today. the planning system was generally more appropriate. 6⎥The Archaeologist Spring 2016 ⎥ Issue 98 Perhaps only now, 25 years after the introduction of PPG 16, are we successful. It protected and conserved archaeology affected by beginning to see the full impact of the extensive assessment, development, enabled a dramatic increase in the understanding of our evaluation and excavation of those years on our understanding of the past, was a major factor in the growth and development of the past, through the synthesis of this material in nationwide research profession, and has been regarded very positively by the planning and projects such as the Roman rural settlement projectand the EngLaid development sectors (including within government) in that it has not project, amongst others. imposed constraints or costs that have affected the viability of developments, or unduly delayed them. Aftermath: heading back in time – the current crisis PPG 16’s success also enabled a relatively smooth transition when for planning and archaeology planning policy on archaeology and the built historic environment was merged as Planning Policy Statement 5 Planning for the historic PPG 16 was the longest-lived of the 25 or so PPGs in operation from environmentin 2010. The short-lived PPS5 was superseded by the the 1980s until 2012, and was widely regarded as one of the most National Planning Policy Framework(NPPF) in 2012, which gives the Cirencester. Credit: Gloucestershire County Council Perhaps only now, 25 years after the introduction of PPG 16, are we beginning to see the full impact of the extensive assessment, evaluation and excavation of those years on our understanding of the past. Roman temple site in Gloucestershire. Credit: Gloucestershire County Council The Archaeologist⎥7 Issue 98⎥ Spring 2016 historic environment a mainstream role as one of the elements of ‘technical details consent’. It is not currently clear how assessment of sustainable development, on an equal footing with other planning archaeological impact will be possible under this new system. PiP is issues. expected to apply to the development of sites on the new Brownfield Register and to local plan development allocations: in other words, to However, the policies for undesignated archaeology in the NPPF are a high proportion of medium- and large-scale development. not (unlike those for scheduled monuments and listed buildings) In parallel with these changes in the planning system, the network of underpinned by specific protective legislation, meaning they are archaeological staff that advises local authorities on proposed relatively vulnerable and subject to changing government policy. The development is being rapidly eroded due to local authority budget current government’s approach to planning policy and legislation cuts, especially in the north of England. This trend seems likely to reflects a general desire to de-regulate, and a specific objective to continue. facilitate house building; the planning system is felt to impede the latter. Consequently, a succession of measures has sought to increase These changes raise the prospect of a return in part to the pre-PPG 16 the scope of permitted development (i.e. developments that can be period, greatly increasing the risk that developments will go ahead carried out without obtaining planning permission, such as house without proper assessment or mitigation of their archaeological extensions below a certain size). The latest – and undoubtedly the impacts, with all the potential problems of unexpected discoveries most dangerous – phase in this process has been the Housing and revealed only after planning permission has been granted. Once Planning Bill 2015–16, which introduces a new two-stage planning again, effective lobbying by the sector is essential if the legacy of PPG application process of ‘permission in principle’ (PiP), followed by 16 is to be sustained into the future. Bourton-on-the-Water Iron Age settlement, 1990s. Credit: Jan Wills Post-PPG 16 evaluation in Hertfordshire, 1995. Credit: Stewart Bryant 1Bryant, S & Thomas, R M, 2015 Planning commercial archaeology and Jan Wills MCIfA (188) the study of Roman towns in England, in M Fulford & N Holbrook (eds) Jan worked on rescue archaeology projects in the Midlands and north The Towns of Romans Britain, the Contribution of Commercial of England during the early part of her career, before moving to a Archaeology Since 1990. Britannia Monograph Series No. 27,7–19. succession of local authority posts where she has managed both curatorial and fieldwork teams. As a county archaeologist she advised on archaeology and development under PPG 16 and its successors. A former Executive Committee member and Chair of ALGAO, and now Honorary Chair of CIfA, she continues to work with sector Stewart Bryant MCIfA (83) partners to influence the development of legislation and policy After graduating from Cardiff in 1979 Stewart worked for the Greater affecting archaeology and the historic environment, most recently the Manchester Unit before moving to Hertfordshire in 1986 as assistant Historic Environment Good Practice Advice in Planningnotes and the to and then as County Archaeologist until 2014. Stewart has also current proposed changes to the planning system. represented ACAO and ALGAO variously as Secretary, Vice Chair and Chair. In these roles he became heavily involved in the failed Heritage Bill and then the production of the archaeological content of PPS5, followed by the NPPF and subsequent guidance and planning advice. Stewart is currently working part-time as a policy advisor for CIfA and he is a council member of the Society of Antiquaries of London. He is also Honorary Research Associate with the EngLaid projectand is actively Jan Wills, pre- pursuing his other research interest – PPG 16. Credit: the later Iron Age. Jan Wills 8⎥The Archaeologist

Description: