Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life PDF

Preview Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life

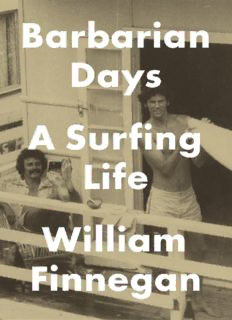

Grajagan, Java, 1979 PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 375 Hudson Street New York, New York 10014 penguin.com Copyright © 2015 by William Finnegan Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Photograph credits Image 1: © Mike Cordesius Image 2: © joliphotos Image 3: © Ken Seino Image 4: © Scott Winer Other photographs courtesy of the author ISBN 978-0-69816374-4 Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. Version_1 for Mollie He had become so caught up in building sentences that he had almost forgotten the barbaric days when thinking was like a splash of colour landing on a page. —EDWARD ST. AUBYN, Mother’s Milk CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph ONE OFF DIAMOND HEAD Honolulu, 1966–67 TWO SMELL THE OCEAN California, ca. 1956–65 THREE THE SHOCK OF THE NEW California, 1968 FOUR ’SCUSE ME WHILE I KISS THE SKY Maui, 1971 FIVE THE SEARCH The South Pacific, 1978 SIX THE LUCKY COUNTRY Australia, 1978–79 Australia, 1978–79 SEVEN CHOOSING ETHIOPIA Asia, Africa, 1979–81 EIGHT AGAINST DERELICTION San Francisco, 1983–86 NINE BASSO PROFUNDO Madeira, 1994–2003 TEN THE MOUNTAINS FALL INTO THE HEART OF THE SEA New York City, 2002–15 ONE OFF DIAMOND HEAD Honolulu, 1966–67 I HAD NEVER THOUGHT OF MYSELF AS A SHELTERED CHILD. STILL, Kaimuki Intermediate School was a shock. We had just moved to Honolulu, I was in the eighth grade, and most of my new schoolmates were “drug addicts, glue sniffers, and hoods”—or so I wrote to a friend back in Los Angeles. That wasn’t true. What was true was that haoles (white people; I was one of them) were a tiny and unpopular minority at Kaimuki. The “natives,” as I called them, seemed to dislike us particularly. This was unnerving because many of the Hawaiians were, for junior-high kids, alarmingly large, and the word was that they liked to fight. Orientals—again, my terminology—were the school’s biggest ethnic group. In those first weeks I didn’t distinguish between Japanese and Chinese and Korean kids—they were all Orientals to me. Nor did I note the existence of other important tribes, such as the Filipinos, the Samoans, or the Portuguese (not considered haole), let alone all the kids of mixed ethnic background. I probably even thought the big guy in wood shop who immediately took a sadistic interest in me was Hawaiian. He wore shiny black shoes with long sharp toes, tight pants, and bright flowered shirts. His kinky hair was cut in a pompadour, and he looked like he had been shaving since birth. He rarely spoke, and then only in a pidgin unintelligible to me. He was some kind of junior mobster, clearly years behind his original class, just biding his time until he could drop out. His name was Freitas—I never heard a first name—but he didn’t seem to be related to the Freitas clan, a vast family with a number of rambunctious boys at Kaimuki Intermediate. The stiletto-toed Freitas studied me frankly for a few days, making me increasingly nervous, and then began to conduct little assaults on my self- possession, softly bumping my elbow, for example, while I concentrated over a saw cut on my half-built shoe-shine box. I was too scared to say anything, and he never said a word to me. That seemed to be part of the fun. Then he settled on a crude but ingenious

Description: