archi & bd la ville dessinée - Dean Motter PDF

Preview archi & bd la ville dessinée - Dean Motter

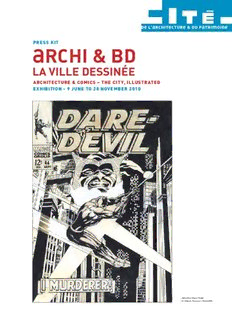

Press kit ARCHI & BD LA VILLE DESSINÉE ArCHiteCtUre & COMiCs – tHe CitY, iLLUstrAteD eXHiBitiON - 9 JUNe tO 28 NOVeMBer 2010 Daredevil, Gene Colan © Galerie 9ème art, Paris 1968 Press kit ARCHI & BD LA VILLE DESSINÉE ArCHiteCtUre & COMiCs – tHe CitY, iLLUstrAteD eXHiBitiON - 9 JUNe tO 28 NOVeMBer 2010 iNAUGUrAtiON - tUesDAY 8 JUNe 2010 Press BrieFiNG COMMeNCes At 5PM Exhibition designed and created by the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine / Institut français de l’architecture Curated by : Jean-Marc Thévenet and Francis Rambert, Director of the IFA Scenography : Projectiles Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine - Palais de Chaillot - 1 place du Trocadéro, Paris 16e (Trocadéro metro station) Open daily from 11am to 7pm except Tuesdays - Open Thursday evenings until 9pm Admission : adult = 8 euros / concession = 5 euros - free for under 12s Press CONtACts Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine Agostina Pinon Tél. 01 58 51 52 85 / 06 03 59 55 26 [email protected] Opus 64 Valérie Samuel et Arnaud Pain Tél. 01 40 26 77 94 [email protected] www.CiteCHAiLLOt.Fr 3 iNtrODUCtiON The Cité plays host to a number of different temporary exhibitions every year on the theme of architecture and the city. Having Jean-Marc Thévenet, former Director of the Angoulême International Comics Festival, organize an exhibition on the theme of the city and comics was a tremendous opportunity for the Cité to become involved in a form of creative and artistic expression that not only has great public appeal, but also has obvious links with the world of architecture and urban development. The city fascinates comic strip artists. Indeed some, like François Schuiten, make it their primary source of inspiration and many use it as a framework, a stage, a means of expressing their perception of contemporary urban reality and their dreams of better cities. Comic strip artists have documented the milestones of the 20th century and modern times and we thought it would be particularly interesting to present these works in chronological order, though a few ‘jumps’ in time have been taken in order to highlight close relationships and affinities between authors of different generations. New York, Paris and Tokyo are cities that are particularly inspirational for comic books and this is reflected in the exhibition. The innovative scenography, designed by Projectiles (winners of the “Young Architects Award”) offers an entertaining opportunity to wander around a mysterious maze where 150 comic book authors and 350 works are presented. In perfect counterpoint to these works, Francis Rambert, Director of the Institut Français d’Architecture, has chosen a selection of sketches, drafts and plans of cities, public buildings and villas – utopias drawn by some of the greatest architects since the beginning of the 20th century – which effortlessly create a dialogue between architecture and comic strip art and highlights the influence of the “9th art” on architects as well as the profound similarity of their imagined realities. François de Mazières Chairman of the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine Le Promeneur, Jirô Taniguchi © Casterman 2008 Taniguchi/Kusumi 4 CO-CUrAtOrs FrANCis rAMBert AND JeAN-MArC tHÉVeNet GiVe Us tHeir iNsiGHt iNtO tHe eXHiBitiON First and foremost, let’s lay down some relevant historical reference points : when did comic strip art embrace the city and when did architecture embrace this form of expression ? JMT : As far as comic strip art is concerned, the first real depictions of the city appeared in the Sunday pages of American newspapers. People appreciated this very popular form of entertainment and a particular favourite is New Yorker Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo character, created in 1905. McCay was fascinated by the burgeoning urban development at the turn of the century, despite the foundation period of the city by pioneers being long gone. FR : The direct influence of comic book art on architecture became evident in the 1960s with the publication of the Archigram magazine created by the group of the same name. The first fictional world of imaginary cities, however, can be found in the visionary drawings of Virgilio Marchi and Antonio Sant’Elia, a young architect of the futurist movement. As early as the turn of the 20th century, when trams and animal-drawn carts were still very much the norm, Marchi was drawing ideal contemporary cities depicting dynamic, mobile concepts. Little Nemo, Winsor McCay, 1907 Bringing up father, George McManus © Peter Maresca and Sunday Press Books © Galerie 9ème art, Paris 1939 5 What does the illustrated city exhibition set out to accomplish ? JMT : The exhibition brings together two different types of creative professionals, architects and comic strip artists, who are fundamentally and above all true visionaries. The comic strip has portrayed the future with surprising insight. The works produced by Enki Bilal or François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters over the last twenty years are proof of that. This exhibition is also a testimonial to how that insight has evolved. Opinions and approaches have changed. Certain considerations, like their meditations on utopias, belong to the past. The voyage, the travel diary, their understanding of the city, the importance of urban décor are highlighted by the prism of intimacy. Also, other lands such as Asia and of course the L’étrange cas du docteur Abraham, Schuiten former eastern block countries are being © Casterman. explored. Schuiten/Peeters 1987 FR : We are constantly being told that there are no more utopias, but we something to dream of, we need to be able to project ourselves into fictional worlds. This exhibition shows that the urban fiction worlds explored by comic strip artists and architects actually cross paths and sometimes even dialogue. Amidst these brief interconnections in a world overrun by screens, tribute has to be paid to freehand drawing. Take Mies van der Rohe’s iconical Friedrichstrasse project drawings, for example, or Hugh Ferris’ tower drawings that transport us into the city of our dreams. And Hans Hollein’s aircraft carrier integrated into a landscape that embarks us on a trip to a radical yet fantasy world. Why exclude comic strip art when exploring the relationship between art and architecture? JMT : Until recently comic book art was considered as a popular genre on a level with science fiction, thrillers and fantasy fiction novels. Art Spiegelman, creator of Maus and à l’ombre des tours mortes recalls : “popular art leaves no mark on the memory”. There was a time when no major artistic or cultural event featured comic books – they were dismissed as trivial and something of a cottage industry. Those days are gone and comic strip narrative style is now actually a reference. The comic strip has become a mainstream communication form even outside the field of comic books. It has an established historical base and a framework (authors, graphical trends…) that are now becoming references in their own right. 6 FR : Obviously, with directors like Godard, Antonioni and Wenders, the film media has been an invaluable source of inspiration for architects. At the same time, the strong visuals of comic strips, rather than any intrinsic reference value, have influenced the way in which some architects present their work. I can give two or three examples : the Danish group BIG who published a book entitled Yes is More, An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution, which is a take on well-known comics and super heros. The super hero in this book is Bjarke Ingels, an architect who appears on almost every page and explains what he is doing as if he were talking at a conference, except that here the media is an album. Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron also opted for a comic strip presentation to present their MetroBasel urban project, complete with frames and speech bubbles. They even took stills of Belmondo and Seberg from a Godard film and inserted them into a metropolitan setting. We could also mention Koolhaas’s Content album, which is a cross between a book and a magazine. Louis Paillard, Stéphane Maupin or Andres Jacque, a young architect from Madrid, are other architects who have used comic strip formats for their work. Although the exhibition is not intended for children, let’s not forget Tison and Taylor’s famous Barbapapa family, inspired by an urban experience in Le Vaudreuil carried out by the Atelier de Montrouge, and which actually serves as a medium for raising awareness about architectural concerns. What is the famous libertarian group Archigram’s vision of the city, given that their architectural designs clearly drew on the graphic traditions of comic art ? FR : The group published a series of comic-strip style magazines Archigram 1, 2, 3, 4, in which they developed new visions on what urban life and society might be like in the future. Projects including Walking City and Plug-in City depicted omnipresent machines, a mechanical and indeed high-tech, yet happy environment in drawings inspired by Pop Art. Those were fabulous times when utopias were born. Alternative groups flourished, like the Haus-Rucker-Co collective in Vienna. Then there was Claude Parent’s phenomenal projects including the spiral City and the cone-shaped City and the raised platforms of Yona Friedman’s Spatial City project. JMT : The first issue of Archigram appeared in 1961, embracing a deliberately utopian vision that could only find scope for expression in the Pop Art-inspired comic strip art form. The early 1960s was a period of optimism fuelled by the impetus of Expo 58 whose success was mainly due to an aesthetically innovative take on everyday objects (transport, clothing, design) and very real visions of what life in the future would be like, with a range of exhibitions devoted to the theme of ‘living in the year 2000’. Belgian authors adopted this aesthetic approach, though in a less contemporary manner than Archigram. This can be seen, to name but a few, in Franquin’s Les Pirates du silence and Will’s Les Aventures de Tif et Tondu. Projet utopique de ville oblique, «Les spirales» - Ponts III, perspective, Claude Parent, 1982 © Collection DAF/ Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine, archives d’architecture du XXe siècle 7 Can comic strips be used as a tool to put across certain ideas, like Rem Koolhaas’s Euralille drawings that are captioned “against the fear of towers” and designed in the style of Spanish artist Mariscal? FR : Koolhaas didn’t use conventional mediums to portray the radically hypermodern Euralille city complex, intended more as a generic hub in a European network rather than merely a place of local identity. The architect has taken a humoristic approach to this enormous project that is conceived as an urban laboratory on the theme of congestion, speed and the “turbo-city” concept. Moreover, it is a patent attempt to seek the approval of the public: only specialists can decipher architects’ plans. The idea behind using comic strip vocabulary is to show that buildings will be alive with energy. That’s what the scenario presentation is all about – just like a Loustal or Bilal album… JMT : On the surface, comic strips are a popular art form and represent the ideal medium for reaching a public audience. However, in reality, this art form is acknowledged for its ability to anticipate future trends and portray current situations. Comic strips are always a today medium. Their great narrative flexibility is a major asset. In addition, as this exhibition demonstrates, there is a close relationship between architects and comic strip artists, as if, at least for the most visionary among them, they share a common genetic code. Comic book art and architecture often cross paths. Jean Nouvel involved comic book authors in a retrospective of his work. Philippe Druillet and Claude Parent have broached the subject of perhaps working together on future projects La maison de verre, Jacques de Loustal © Jacques de Loustal 2007 How many plates will be exhibited? JMT : 350 works will be on display. The aim of the exhibition is not to provide an exhaustive review or an encyclopaedic vision of the art form, but rather to present a selection of the most significant and representative works of the last century. The exhibition is not a mere documentation of architectural design, but an exploration of imaginary urban landscapes. In view of this, Tokyo is voluntarily represented from a more European angle in the works of Frédéric Boilet or those of Taniguchi, who is Japanese but writes narrative with a decidedly western flavour. It became essential to show the mood of the city as in the works of Ceesepe, Spanish author and one of the symbols of the ‘Movida’ movement of the early eighties. In response to Ceesepe, are the works of Benjamin, a young Chinese author from a different century. The 20th century Movida has yielded way to an apocalyptic vision of 21st century metropolises. The ultimate aim is to present comic strips that take inspiration in various, unexpected medias: paintings, video clips. Each work conveys its own individual meaning and message. The polished graphic talents of certain authors sit side by side with more impressionist works that are essential to our comprehension of the ties that exist between comic strip art and illustrated cities. FR : Almost a hundred architectural documents will form part of this dialogue of artistic creativity, including several very special works such as James Wines’ “Highrise of Homes” which is a critical approach to architecture and urban planning. Wines, who is the founder of the SITE group, draws a high-rise residential complex with individual houses with gardens on every level. Why couldn’t we have a house in the city ? This drawing is representative of a sociological and urban reality. It raises the question of innovative, utopian vision, which is of particular interest. Through their imaginary visions of urban life, comic strip artists are telling a story. Sometimes this story is pure invention. Indeed, architects often use comic strip art to inject a futuristic dimension to their projects. Jacques Rougerie’s book Habiter la mer is a genuine comic strip album inspired by Jules Verne. The architect used comic strip art to tell a fictional, futuristic story about the discovery of an underwater world. One can recall Patrice Novarina, an architect who enjoys dabbling with panels and speech bubbles, submitting a proposal for the Babelsberg development project (the Potsdam cinema studios where The Blue Angel was filmed) in comic strip form. 8 What can you tell us about Projectiles’ scenography? FR : The scenography is extremely flexible, punctuated with a succession of different rhythms. The challenge was to avoid repetitive displays of small plates. The scenography has been arranged to that the walls appear to be mobile. Large format documents have been placed aside small drawings. There will also be events on the theme of Pierre Chareau’s Glass House. Antoine Mathon, great-grandson of the famous Parisian house’s original owner and client has asked four artists (Loustal, Jean-Claude Götting, André Juillard and François Avril) to give their take on a fragment of the history of this architectural masterpiece. There is an intermingling, not a confrontation of references. Architecture draws inspiration from comic strip art, and comic strip art draws inspiration from architecture. JMT : The scenographers were faced with a double challenge: rhythm and light. Both elements are essential for a comic book exhibition to be successful. The use of varied graphics and the format of the plates are, over the duration of an exhibition, important factors in making the experience pleasurable for visitors. Exhibiting original artwork in this case was the obvious choice, however the role of the scenographers was to make the presentation less museum-like and more contemporary, so enlargements of plates and panels are used to vary the visual rhythm and offer a new approach on a number of works. Most authors spontaneously agreed to have their works englarged. Savior, Benjamin © Xiao Pan 2010 The city themes focus mainly on New York and Japan, but are we witnessing a move towards other emerging metropolises? FR : Yes, but that’s a normal phenomenon. Our attention is always attracted to where the buzz is, for example the mushrooming cities of China. It is interesting to see that the iconic architecture that is popping up all over China is already extremely present in comic strip art. A good example would be Zou Jian, the Chinese author who has already depicted the big arch of Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV tower in his Beijing Chronicles. These remarkable architectural works have made a huge impact on urban space and have consequently made their way into stories. Having said that, there will always be stories in New York’s Brooklyn district, that Paul Auster is so fond of, that are waiting to be illustrated and that have already been adapted by David Mazzucchelli. JMT: The comic strip community is fuelled by young authors that are in touch with their time. China is definitely one of the emerging comic strip continents, and India will shortly be following suit. For a long time China happily churned out sketchbooks for mass audiences that copied, illegally of course, the adventures of Tintin. Comic strip art was considered as decadent and took a long time to develop. In opening up to the world, comic strip art has been ‘decompartmentalized’ and no longer has an ethnocentric vision. It is no longer Franco-Belgian or American or Asian, it covers all continents. Mediums like blogs encourage cross-border and cross-cultural exchanges that reinforce the dynamics of comic strip art in its most international form. 9 Is the chaos of urban life, a theme that fascinates architects, depicted in Japanese comic art? JMT: The chaos of urban life is universal in comic strip art! The city and its ability to be a source of stress is omnipresent in certain manga presented here such as Tekkon Kinkreet by Matsumoto and 20th Century Boys by Urasawa as well as in the reinterpretation of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis by the grand Japanese master Tezuka. Chaos can take many forms: there is the physical chaos depicted in manga or certain modern comics that make American metropolises look like they are in the middle of a civil war. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to say pressure rather than chaos. But a psychological pressure suffered by a hero who is more often than not dominated by the environment in which they live. This is a concept that is clearly defined in the works of authors such as Chris Ware, Adrian Tomine and Daniel Clowes to name but a few FR : In some comic strips, what is important is that the main character is roaming in a city – the actual city need never be explicitly mentioned, like in Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation. In architecture, the portrayal of urban landscapes requires precision. Cinema, comic strip art and architecture can intertwine in many ways, and evidence of this is the importance of the storyboard in the works of directors like Terry Gilliam and Jean-Jacques Beineix, the same tool that architects use to illustrate cities for competitions and publications. The ultimate aim of the exhibition is to show that these disciplines mutually overlap, that they are not self-contained. Has information technology had as great an impact on comic strip art as it has had on architecture and urban development? JMT : Information technology has enabled artists to radically increase the input in comic strip creation. Artists need no longer do with just a plate. They can divide up the story into a succession of images. The sequential nature of comic strip art has changed as a result. Each individual panel of a composition can be read as a whole. An emerging theory in comic strip art is that it can be read as much as it can be looked at. This vision is broached in the last part of the exhibition that covers the subject of new outlets for comic strip art. The use of information technology brings us closer to other mediums, such as video games, which are embracing new graphic technologies. The influence of these strong visuals can be seen in new- generation comics or other more personal works. FR : Whatever graphic evolution takes place, the drawings will always be a visual critique of the city: Tardi who always focuses on the Haussmann buildings of the old town, Sempé who has just published a truly poetic book about New York (you can really tell he loves that town)… in this case it is an endearing critique. Then there are more severe critiques like that of Reiser who addresses the issue of architecture. JMT : …every small part ends up being part of a whole, one single vision of the city: “isn’t that how men live?” Interview by Sophie Trelcat 10

Description: