Archaeological Researches at Teotihuacan, Mexico PDF

Preview Archaeological Researches at Teotihuacan, Mexico

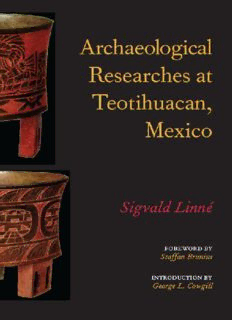

ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCHES AT TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCHES AT TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO Sigvald Linne Foreword by Staffan Brunius Introduction by George L. Cowgill THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa Copyright © 2003 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Originally published in 1934 by The Ethnographical Museum of Sweden Typeface is AGaramond The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Linne, Sigvald, 1899- Archaeological researches at Teotihuacan, Mexico / Sigvald Linne; foreword by Staffan Brunius ; introduction by George L. Cowgill. p. em. Originally published: Stockholm: V. Petterson, 1934. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8173-1293-0 (doth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8173-5005-5 (paper: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8173-8379-4 (electronic) 1. Teotihuacan Site (San Juan Teotihuacan, Mexico) 1. Title. F1219.l.T27L55 2003 972'.52-dc21 2002041617 CONTENTS Foreword: The Early Swedish Americanist Tradition and the Contributions of Sigvald Linne (1899-1986) VII Staffan Brunius Introduction to the 2003 Edition: Xolalpan after Seventy Years XIII George L. Cowgill Archaeological Researches at Teotihuacan, Mexico 1 Sigvald Linne Appendices 162 Works Consulted 221 Index 234 FOREWORD The Early Swedish Americanist Tradition and the Contributions of Sigvald Linne (1899-1986) Staffan Brunius I n the 1920s the university and the ethnographical museum of Gothenburg (Goteborg), the busy seaport city, were the institutions to attend for an academically competent and internationally well respected Swedish education in American Indian cultures. This high quality ethnographical-anthropological training was the result of one man's extraordi nary achievements-those of baron Erland Nordenskiold (1877-1932), the prominent Swedish americanist. Since the end of the 1890s Erland Nordenskiold had devoted his life to South America, first as a zoologist but soon turning to ethnography, archaeology, and (ethno-)history. His extensive fieldwork, his productive authorship, his devotion to stu dents, and his professional museum experience made him a respected and beloved teacher and supervisor. Many of Erland Nordenskiold's students would, indeed, over time make acclaimed americanist contributions of their own. These students included Sven Loven (1875-1948), Karl Gustav Izikowitz (1903-1984), Gosta Montell (1899-1975), GustafBolinder (1888- 1957), Alfred Metraux (1902-1963), Stig Ryden (1908-1965), Henry S. Wassen (1908- 1996), and Sigvald Linne. Through their teacher they would not only receive theoretical and, in most cases, fieldwork training, they would also be familiar with archival research and museum work. Following the example of Erland Nordenskiold, most of these students would as americanists concen trate almost exclusively on South America, except for Sigvald Linne who primarily, but certainly not exclusively, focused his research work on Lower Central America and Mesoamerica. Erland Nordenskiold's importance to the high standing of Swedish americanist research during the first half of the 1900s can not be underestimated. However, it must be empha sized that Nordenskiold was not the first Swede to study the American Indian. If we expand the meaning of the "americanist" concept, we find that such interest in Sweden traces its roots to the New Sweden colony (1638-1655) that covered approxi mately the present state of Delaware. From the colony derive documents with ethnographical This foreword is reprinted in the companion volume by Sigvald Linne, Mexican Highland Cul tures: Archaeological Researches at Teotihuacan, Calpulalpan and Chalchicomula in 1934-35. information, (ethno-)historical sources that have proved to be important for the study of the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. In Sweden this early interest was, not surprisingly, mostly limited to the absolute upper echelon of the Swedish society and often manifested in the time typical of Kunst und Wunderkammer (Art and miracle chambers) established in the castles and mansions of the royalty and aristocracy. The very earliest American Indian col lections in Sweden were, indeed, "curiosities" from this very period-a fact that would catch the attention of the broadly oriented Sigvald Linne later in his career (see, for ex ample, his articles Drei alte Waffin aus Nordamerika im Staatlichen Ethnographischen Mu seum in Stockholm [1955] and Three North American Indian Weapons in the Ethnographical Museum o/Sweden [1958]). From the 1700s and onward, ethnographical and Precolumbian collections from the Americas were increasingly gathered and systematically organized at universities and vari ous cabinets of naturalia, such as at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences founded in 1739. In the 1800s Swedish travelers visited the New World in greater numbers and some times described in accounts their meetings with Indians. One of those travelers was Fredrika Bremer (1801-1865) in the early 1850s. Then in the latter part of the 1800s true americanist efforts with published results were made by Swedish natural scientists, early archaeologists, and ethnographers, including such people as Carl Bovallius (1849-1907), working prima rily in Costa Rica and Nicaragua in the 1880s and later in northern South America; Eric Boman (1867-1925), working in Argentina and adjacent areas; GustafNordenskiold (1868- 1895), the elder brother of Erland Nordenskiold, working in the early 1890s in Mesa Verde in the southwestern United States; Axel Klinckowstrom (1867-1933), working in the early 1890s in northeastern South America; and Carl V. Hartman, working in the 1890s in northern Mexico, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. Instrumental for Carl V. Hartman's pio neering archaeological work in Costa Rica was Hjalmar Stolpe (1841-1905). Stolpe was himself a natural scientist, archaeologist, and an americanist, and he had researched Ameri can Indian ornamental art as well as the archaeology of Peru during the Swedish Vanadis expedition that circumnavigated the world from 1883 to 1885. Erland Nordenskiold had an important influence on Linne, but Hjalmar Stolpe's influence can not be underestimated either. Influenced by currents abroad, Hjalmar Stolpe in the early 1870s helped promote the founding of a Swedish anthropological society, later The Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography. Its prestigious journal Ymer became attractive for the early americanists in Sweden. Furthermore, impressed by what he had seen in Copenhagen, Hjalmar Stolpe was instrumental in the founding of an ethnographi cal museum in Stockholm, which traces its roots via the Museum of Natural History to the previously mentioned cabinet of naturalia of The Royal Academy of Sciences. Hjalmar Stolpe became the first director of this ethnographical museum in 1900, which today is The National Museum of Ethnography (Etnografiska Museet). It was at this very museum that Linne began his work in 1929 and for which he was the director from 1954 to 1966. V111 / Staffan Brunius Through the museum, he would publish his major works, and many of his shorter articles appeared in its journal Ethnos, first published in 1936. Linne recognized the importance of history-the history of learning, the history of ethnography-anthropology, and particularly the history of americanist research, especially as it had developed in Sweden. He had detailed knowledge about the Kunst und Wunderkammer and cabinet of naturalia periods, about his americanist predecessors, about Hjalmar Stolpe's ambitious ethnographical exhibition venture in Stockholm from 1878 to 1879, about the contents of the Swedish contributions to and the network of contacts that developed at the American-Historical Exhibition in Madrid 1892, and about the organiza tion of and contributions at the International Congress of Americanists held in Stockholm in 1894 and in Gothenburg (together with Haag) in 1924. This historical knowledge was probably an expression of a sincere intellectual curiosity; however, the academic training under Erland Nordenskiold also emphasized the impor tance of using (ethno-)historical sources in archaeological and ethnographical research. One of Linne's major publications, EI Valle y La Ciudad de Mexico en 1550 (1948), which discussed the oldest preserved map of Mexico City kept at Uppsala University library, cer tainly reflects his interest in history. Already in 1939 Linne had presented his initial re search about the contents and the background of the map at International Congress of Americanists held in Mexico City, one of the many international congresses and confer ences in which he participated. When Linne approached Erland Nordenskiold in Gothenburg in the mid-I920s he had already left behind studies in the natural sciences (chemistry). Obviously Nordenskiold made a deep impression, because from then on Linne changed his focus of study to archae ology and ethnography of the Americas. Nevertheless, he always recognized the impor tance of the natural sciences, and his first major graduate work, The Technique of South American Ceramics (1925), included microscopic analysis. It received fine reviews from Alfred Kroeber in American Anthropologist, and much later, in 1965, it was praised as a "major pioneer work" in a volume from the "Ceramics and Man" symposium held in 1961 at Burg Wartenstein. The following major work as a student for Erland Nordenskiold was his dissertation, Darien in the Past: The Archaeology ofE astern Panama and Northwestern Colombia (1929), based on fieldwork during Erland Nordenskiold's last expedition in 1927 to Colombia and Panama. Again reviews in American Anthropologist praised the work: Alfred Kroeber wrote that "the Goteborg technique and standard of scholarship are thoroughly upheld." Inter estingly enough, the great authority Doris Stone maintained as late as 1984 that Linne's work from 1929 was still the best for that particular area. In 1929 Linne moved from the west coast of Sweden back to his native Stockholm, having received a position at the ethnographical museum. The previous director of the museum, Costa Rica expert Carl V. Hartman, had retired, and the africanist Gerhard Lindblom was the recently appointed new director. Much work was needed to organize the Foreword / IX

Description: