Apex Science Fiction and Horror Digest 11 PDF

Preview Apex Science Fiction and Horror Digest 11

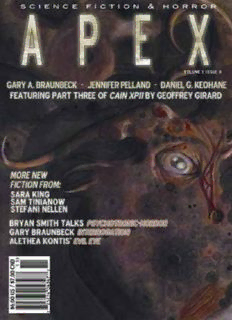

Apex Publications, LLC www.apexdigest.com Copyright ©2007 by Apex Authors First published in 2007, 2007 NOTICE: This work is copyrighted. It is licensed only for use by the original purchaser. Making copies of this work or distributing it to any unauthorized person by any means, including without limit email, floppy disk, file transfer, paper print out, or any other method constitutes a violation of International copyright law and subjects the violator to severe fines or imprisonment. What Say You Editorial by Jason B Sizemore Congratulations to Justin Stewart, our resident artist and content designer, for his Chesley Award nomination. Although he didn't win, nobody will deny that being recognized by the top SF/Fantasy art awards in the country isn't damn cool. Justin has been with us since the genesis of Apex Digest. He did the covers for our first four issues, all free of charge. He continues to do amazing work for Apex, be it creating advertising art, banners, flyers, book covers, etc. Without Mr. Stewart, there would probably be no Apex Digest. Congratulations, Justin, on your nomination. Next year, please win. Jason Sizemore: Editor in Chief Gill Ainsworth: Senior Editor Deb Taber: Editor/Art Director Alethea Kontis: Contributing Editor Mari Adkins: Submissions Editor Jodi Lee: Submissions Editor Justin Stewart: Content Designer E.D. Trimm: Copy Editor Cover art by Nigel Sade Subscription Rates: $20 for one year (four issues), or $6 for a single issue. International is $34 for a subscription and $11.00 for a single issue. Subscriptions and single issues may be obtained from Jason Sizemore c/o Apex Digest. Apex Science Fiction & Horror Digest is a publication of Apex Publications, LLC and is distributed four times a year from Lexington, Kentucky. Copyright © 2007 all rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reprinted in whole or in part without written permission. ISSN: 1553-7269 Apex Science Fiction & Horror Digest PO Box 24323, Lexington, KY 40524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.apexdigest.com Table of Contents: Blackboard Sky—Gary A. Braunbeck Interview with Gary A. Braunbeck Spinnetje—Stefani Nellen Ray Gun—Daniel G. Keohane Uncanny—Samuel Tinianow Curses of Nature—Alethea Kontis The Moldy Dead—Sara King Interview with Bryan Smith Cain Xp11 (Part 3): Sorry About the Blood—Geoffrey Girard What to Expect When Expectorating—Jennifer Pelland Gary A. Braunbeck writes mysteries, thrillers, science fiction, fantasy, horror, and mainstream literature. He is the author of 19 books; his fiction has been translated into Japanese, French, Italian, Russian and German. Nearly 200 of his short stories have appeared in various publications. He was born in Newark, Ohio, the city that serves as the model for the fictitious Cedar Hill in many of his stories. The Cedar Hill stories are collected in Graveyard People and Home Before Dark. His fiction has received several awards, including the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Short Fiction in 2003 for “Duty” and in 2005 for “We Now Pause for Station Identification,"; his collection Destinations Unknown won the Fiction Collection Stoker in 2006. His novella “Kiss of the Mudman” received the International Horror Guild Award for Long Fiction in 2005. For more information about Gary and his work, please visit: www.garybraunbeck.com. BLACKBOARD SKY By Gary A. Braunbeck "Children of the future age. Reading this indignant page, Know that in a former time, Love, sweet love, was thought a crime..." —John Milton, A Little Girl Lost # When I was six years old I fell down the stairs of our house and cracked my spine. Had it been one centimeter deeper I would have been paralyzed for life, but as luck would have it the injury required only one surgery followed by months of bed-rest, during which I could only move my arms or have my head propped up on pillows when it was time to eat. I read hundreds of books during those months, learned how to play poker from my mother, and drew so many pictures my father threatened to wallpaper every room in the house with them if I didn't stop. To save both paper and his nerves, he devised a contraption with hooks and pulleys that enabled me to raise or lower a small blackboard above my bed, allowing me to lie on my back (I was supposed to remain flat as often as possible) and draw pictures with the dozens of pieces of different-colored chalk he purchased at an art supply store. I thought of it as my blackboard sky. Some of the chalk was of the glow-in-the-dark variety, and every night before I fell asleep I would draw a picture of a guardian angel so that if I woke up in the middle of the night, frightened, I had only to look above to see my glowing angel with its luminous wings, and I'd know that I was all right, I was protected, someone was watching over me. If it weren't for that, if I'd not had my blackboard sky on which to depict glowing guardian angels and the dreams of all I planned on doing once I could walk again (flying to the moon in a rocket ship was right at the top of the list), I think my head would have started ticking like a bomb on a subway train, and I would have gone stark, staring crazy by the time I was seven. I still have that blackboard, and every so often I take it out of the closet and spend a half-hour or so drawing on it, just to remind myself that at least I had an outlet as a child when one was so desperately needed. Or, rather, I used to. I used to do a lot of things, look forward to things, plan for things, hope for things. And then came the story of the Boy in the Box Tower. # The first part was jammed between pages 93 and 94 of a used paperback edition of Anton Chekhov's The Party and Other Stories on a stained piece of notebook paper that looked as if someone had spilled coffee on it and then, in anger, crumpled it into a wad and thrown it away, only to have someone else later find it, smooth it out, and write on it. The handwriting (printing, actually) was that of a child—perhaps 7 or 8 years old—and if the spelling, punctuation, and grammar were any indication, not a particularly bright child; but I stopped thinking about those things by the time I reached the end of the first paragraph: The boy In the boxTower befour he was calld the boy in the Boxtower his name was vincent. he was not like everyone else. he was difrent. he had a special gift for distruction. vincent could distroy anything just buy looking at it when he was upset. he hated it but didn't no what he could do too stop it. it was resess and all the forth-graders went outside too play. vincent walked too a corner of the playground and sat alone. he didn't hav friends. everyone thought he was a freek. vincent wasn't intoo math or science or reeding or righting or history. he was intoo horror and ghosts and creetsures and aleyans frum space in books and movees. he yousd to watch horror movees with his dad befour his dad got all sad and killed himself. that was why vincent was always depressed. he never reelly talked two people or got along with anywon. he was always alone, even when he was home with his mom who was always drunk and on the fone with her sister asking four monee to help with the bills. a kid was walking to vincent, a big kid. "hay, freek!” the kid shouted at vincent. then he hit vincent in the face hard. vincent fell back but then got up. vincents nose was bleeding and his left eye began to twitch. "you would not bee like this if yore dad wasn't mean and hit you all the time,” said vincent to the big kid. "well at leest my dad is alive and not some psycho who killed himself!" vincent grabbed a big rock and beat the kid in the face with it. the kids face all bloody. vincent stood with tears in his eyes. the twitch in his eye went faster. he felt very hot inside. all the heat like fire heded to his eyes. vincent stared at the kid with the bleeding face. with his eyes he made the bleeding kid go on fire all over. the big kid started screeming reel loud. vincent cryd harder and took off running until he reechd the big tower of cardbored boxes. it took him 7 hours to climb to the top of the tower where there was a room for him to hide. noone new where he went, but they started looking four him. but vincent was not alone in the box tower. the device was there with him. the device always found him. the device was his only friend. "That is seriously fucked-up,” came a woman's voice from behind me. I started, nearly knocking over the stack of books I'd been inventorying, and turned to see that Claire, who worked one of the cash registers, was standing there reading over my shoulder. "Jesus, Claire! Have you been taking some kind of ninja training on your days off? I never heard you." "You were so engrossed in that, I just knew it was something odd." I tilted my head and grinned. “You were hoping it was another twenty, weren't you?" "Can you blame me?" I'd once found a twenty dollar bill inside a well-read copy of Love Story. Claire and I—along with the other volunteers who'd been working that night—had used it to order a pizza. The place we work is called, simply, BARGAINS. It's a second-hand store, not unlike those run by Goodwill and the Salvation Army, where people who can't afford to shop at regular department stores come to buy clothes, furniture, household appliances, televisions, VCRs, DVD players, assorted other electronics ... and, of course, books. I volunteer on Friday nights and Saturdays, and am in charge of the electronics and books sections. (I'd taken the day off work on this particular Friday because of a too-long doctor's appointment, and had decided to come into the story early.) I make it a point to always go through every box of donated books that comes in and remove anything left inside. Over the years I have found concert tickets, bank receipts, phone numbers, addresses, photographs of people whose names I'd never know, money, candy bar wrappers ... people will use the damnedest things as bookmarks, and then forget to remove them before tossing the books into the large metal BOOK DONATIONS bin outside the store. I'd once suggested that we request people leave their names when donating books in case something of value was found inside, but the store has no computer to create such a database, and even if it did, cataloguing who donated each book would soon become a full-time endeavor; so, instead, I go through each book before placing it on the shelves. "There's more on the back,” said Claire. I turned over the page and there, in the same childish handwriting, was this: .... the device was sending him a message, so vincent listened very carefully. he