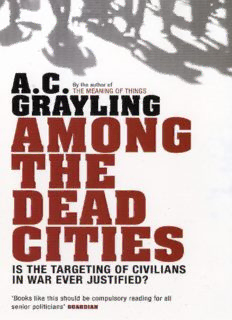

Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan PDF

Preview Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan

AMONG THE DEAD CITIES The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan A. C. Grayling For Madeleine Grayling, Luke Owen Edmunds, Sebastian, Thomas, Nicholas and Benjamin Hickman and Flora Zeman who are our future and need us to do justice in all things. ’The term “war crimes” … includes … murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population before or during the war.’ US State Department to the British Ambassador in Washington, 18 October 1945 Contents 1 Introduction: Was it a Crime? 2 The Bomber War 3 The Experience of the Bombed 4 The Mind of the Bomber 5 Voices of Conscience 6 The Case Against the Bombing 7 The Defence of Area Bombing 8 Judgement Maps Appendix Acknowledgements Bibliography Notes A Note on the Author Picture credits Other Books By the Same Author 1 Introduction: Was it a Crime? In the course of the Second World War the air forces of Britain and the United States of America carried out a massive bombing offensive against the cities of Germany and Japan, ending with the destruction of Dresden and Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Was this bombing offensive a crime against humanity? Or was it justified by the necessities of war? These questions mark one of the great remaining controversies of the Second World War. It is a controversy which has grown during the decades since the war ended, as the benefit of hindsight has prompted fresh examination of the ‘area bombing’ strategy – the strategy of treating whole cities and their civilian populations as targets for attack by high explosive and incendiary bombs, and in the end by atom bombs. Part of the reason why the area-bombing controversy continues to grow is that in today’s Germany and Japan people are beginning to speak about what their parents and grandparents endured in the bomber attack, and to see them as victims too, to be counted among the many who suffered during that immense global conflict. What should we, the descendants of the Allies who won the victory in the Second World War, reply to the moral challenge of the descendants of those whose cities were targeted by Allied bombers? This fact – that the descendants of the bombed have begun to raise their voices and ask questions about the experience of their parents and grandparents – provides one powerful reason why it matters today to try to reach a definitive settlement of the controversy. Another and connected reason is that history has to be got right before it distorts into legend and diminishes into over-simplification, which is what always happens when events slip into a too-distant past. At time of writing there are still survivors of those bombing campaigns, both among those who flew the bombers and those who were bombed by them. Historians of the future will in part be guided by judgements we make now. With our proximity to the war, its survivors still in our midst or close to our personal memories, but with the hindsight of a generation’s length from the events, what we say will help shape the future’s understanding of this aspect of the Second World War. A third and even more contemporary reason for revisiting Allied area bombing is to get a proper understanding of its implications for how peoples and states can and should behave in times of conflict. We live in an age of tensions and moral confusion, of terrorism and deeply bitter rivalries, of violence and atrocity. What are the moral lessons for today that we can learn from the vast example of how, when bombing brought civilians into the front line of the conflict in the Second World War, the Allies acted? In the decades after 1945 these implications were obscured by the fact that a much larger and more important moral matter occupied the mental horizon of the post-war world, and quite rightly so – the Holocaust. This egregious crime against humanity was a central fact of Nazi aggression and the racist ideology driving it, and in comparison to it other controversies seemed minor. Other controversies do not fade through lack of attention, but grow unnoticed, until – as we have seen in recent years with neo-Nazi efforts to exploit the victimhood of the bombed for their own political purposes – they become a worse problem than if they were addressed with clarity, frankness and fairness. In all these ways a new urgency attaches to the question: did the Allies commit a moral crime in their area bombing of German and Japanese cities? This is the question I seek to answer definitively in this book. To explain my personal motivation for trying to answer this question, I need only describe what I can see from where I sit writing these words. There is a small park across the road from my house in south London, completely grassed over, with a scattering of chestnut and linden trees standing in it. The trees have been growing there for half a century, and are close to maturity. As always, the chestnuts are first to break into leaf in spring; in the height of summer the lindens’ tassels of yellow flowers make a fine show against the dark green of their heart-shaped leaves. It is easy to judge the age of these trees, because the open space in which they stand became a park just a little over fifty years ago, so the trees and their park began life together. Before then, for a few years, that open space was filled with ruins, a bare scar of bricks and rubble cleared to ground level. Before then again it was a row of houses; a dozen of them, three- storeyed semidetached Victorian villas identical to the others still standing near by -one of them being the house where I live, and from whose windows I look out. The green and tranquil appearance of this little London park belies the reason for its existence. It is in fact a Second World War bombsite. The houses that stood there were blown up in the Blitz of 1940-1. It is possible to follow the line of bombs that destroyed them as they fell in this street, to be succeeded by more falling in the next street – there is a little park there too, also with fifty-year-old linden trees – and on to the very big park just beyond. Until 29 December 1940 this big park was not an open stretch of grass and playing fields, but a tangle of crowded built-up streets on either side of the Surrey Canal. It is now, as a result of one of the worst nights of the Blitz on London, an expanse of 120 acres containing football and cricket pitches, a lake, cycling paths, shrubberies, and avenues of trees. Here and there stubborn protuberances of broken brick and concrete remain, half buried beneath ivy, with some ruined adjoining walls standing beside them. One street is left intact in the park, with houses along one side and a stoutly constructed Victorian school on the other, still alive with children each day in term time (my youngest child began her education there). The street and its school protrude into the park’s open spaces as a reminder of what had been a densely crowded urban scene, and therefore as a memorial to the nights when bombs rained down on London, killing and destroying. Contemplating the street where I live and the surrounding area, I am daily reminded of the horrors of that time, and the memory drives home a point too often forgotten once wars end and memories dim: that in discussions of war and its effects on humanity, there is an argument that says that deliberately mounting military attacks on civilian populations, in order to cause terror and indiscriminate death among them, is a moral crime. Is this assertion – ‘deliberately mounting military attacks on civilian populations is a moral crime’ – an unqualified truth? If it is, people in today’s Western democracies must revisit the recent past of their countries to ask some hard questions about their behaviour in the great wars of the twentieth century, so that the historical record can be put straight. Attacks on civilian populations have often happened in wars throughout history, but this fact does not amount to a justification of the practice. If ever such a practice could be justified or at least excused, it will be because the following questions have received satisfactory answers. Are there ever circumstances in which killing civilians in wartime is morally acceptable? Are there ever circumstances – desperate ones, necessities, circumstances of danger to which such actions are taken as a defensive measure – that would justify or at least exonerate turning civilians into military targets? Can there be mitigating factors that would compel us to withhold the harshest judgement from those who planned and ordered such attacks? If one committed a crime in preventing or responding to a worse crime, would that mitigate or – more – even excuse the former? We need to know the answers to these questions, because they are crucial to resolving the controversy about Allied area bombing in the Second World War. It cannot be right to hold that the mere fact of being a victor in a conflict sanitises one’s actions; if questions arise about the morality of what one’s own side did in winning a war, they should be squarely addressed and honestly answered. Because moral questions about Allied area bombing (otherwise called ‘carpet bombing’, ‘saturation bombing’, ‘obliteration bombing’ and ‘mass bombing’) are deeply controversial, they arouse strong feelings. In discussion of these questions – discussion that began during the war itself – there have been outright defences of the Allied bombing campaigns (on various grounds but mainly that of military necessity) and outright condemnations, the former by far in the majority. Alternatively writers have said, ‘this question is too difficult, and must be left to philosophers to debate’. This last is the challenge taken up here. Two things must be made emphatically clear at the outset. First, it is unquestionably true that if Allied bombing in the Second World War was in whole or part morally wrong, it is nowhere near equivalent in scale of moral atrocity to the Holocaust of European Jewry, or the death and destruction all over the world for which Nazi and Japanese aggression was collectively responsible: a total of some twenty-five million dead, according to responsible estimates. Allied bombing in which German and Japanese civilian populations were deliberately targeted claimed the lives of about 800,000 civilian women, children and men. The bombing of the aggressor Axis states was aimed at weakening their ability and will to make war; the murder of six million Jews was an act of racist genocide. There are very big differences here. But if the Allied bombing campaigns did in fact involve the commission of wrongs, then even if these wrongs do not compare in scale with the wrongs committed by the Axis powers, they do not thereby cease to be wrongs. The figure of 800,000 civilians killed by Allied bombing, almost all of them in the course of deliberately indiscriminate attacks on urban areas, is staggeringly high in its own right, and even so says nothing about the injured, traumatised and homeless, who in many respects suffered worse. The debate about the question has often been clouded by comparing what the Allies did with what the Axis did in the way of immoral actions, always (and rightly) to the credit of the Allies – only to leave the matter there, as if drawing the comparison by itself resolves matters. It does not; which is the reason for revisiting the question and trying to settle it. But nothing in this book should be taken as any form of revisionist apology for Nazism and its frightful atrocities, or Japanese militarism and its aggressions, even if the conclusion is that German and Japanese civilians suffered wrongs. A mature perspective on the Second World War should by now enable us to distinguish between these two quite different points. Revisionist excuses for Nazism are unacceptable, and it has to be acknowledged that large numbers of people in Germany in the Nazi era, quite possibly the majority of them, supported Hitler in much of what he did. This has made many think that the civilian populations of the Axis countries deserved what they got, and that therefore it is a waste of time wringing one’s hands over the question whether the Allies committed wrongs. But – again -such an attitude will not do. An SS trooper who machine-gunned unarmed Jews in an open pit might merit a death sentence for the crime; but a civilian who had given Hitler a stiff-arm salute and approved of his policies, and who otherwise worked as (say) an accountant, scarcely merits being executed (by bombing) for doing so. And whereas an SS trooper would be identified and prosecuted before punishment, the Nazi- supporting accountant might die in a civilian bomb shelter alongside someone who disliked Hitler and did not support the Nazis’ war. Thus even if the first person’s death were merited by the mere fact of his Nazism – which it is not – his companion’s death would be too high a price for it. In any case, these thoughts do not address the main point, which remains that if the Allies countered great Axis wrongs with lesser wrongs, the latter remain wrongs. Still – and here the need for nuance enters – justice requires that one ask, Was it the case that these wrongs – if such they were -committed in countering greater wrongs, were unavoidable or necessary? Is there a plea of justification or mitigation that can be entered in their behalf, if they need either? For one must remember this: killing a man is wrong; but if one man kills another in self- defence, or in defending his family from murderous attack, the wrong in question at least becomes subject to qualification. So this too has to be taken into account, once the full picture has been considered. The second thing that must be emphatically clear is that this examination of the moral status of Allied area bombing is not intended to impugn the courage and sacrifice of the men who flew RAF and USAAF bombing missions over Nazi-dominated Europe. Criticism – or even merely discussion – of the morality of the Allied bombing campaigns has often been read as tantamount to impugning the contributions made by those aircrews, and as devaluing their sacrifices in fighting what was after all a just war, and a necessary one, against wicked and dangerous aggressors. Nothing in this book should be taken as detracting from the bravery of those

Description: