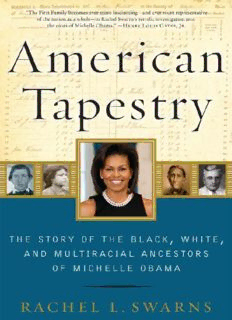

American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama PDF

Preview American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama

AMERICAN TAPESTRY THE STORY OF THE BLACK, WHITE, AND MULTIRACIAL ANCESTORS OF MICHELLE OBAMA RACHEL L. SWARNS Dedication TO THOSE WHO CAME BEFORE Contents Cover Title Page Dedication PROLOGUE: The Mystery of Michelle Obama’s Roots PART I - Migration ONE - Phoebe, the Wanderer TWO - St. Louis THREE - Siren Song of the North FOUR - A Family Grows in Chicago FIVE - Exploding Dreams SIX - A Child of the Jazz Age SEVEN - A Man of Promise EIGHT - Stumbling Backward NINE - Love in Hard Times TEN - Struggling and Striving ELEVEN - The Search for the Truth: Cleveland PART II - The Demise of Reconstruction and the Rise of Jim Crow TWELVE - A Man on the Rise THIRTEEN - Left Behind FOURTEEN - Neither Black nor White FIFTEEN - The Reckoning SIXTEEN - Birmingham, the Magic City SEVENTEEN - Two Brothers, Two Destinies EIGHTEEN - The One-Armed Patriarch NINETEEN - Twilight TWENTY - The Search for the Truth: Atlanta PART III - Slavery and Emancipation TWENTY-ONE - A Slave Girl Named Melvinia TWENTY-TWO - Journey to Georgia TWENTY-THREE - South Carolina Gold TWENTY-FOUR - A Child Is Born TWENTY-FIVE - Born Free TWENTY-SIX - Exodus TWENTY-SEVEN - The Civil War TWENTY-EIGHT - Uneasy Freedom EPILOGUE: Melvinia’s Secret Acknowledgments Notes Bibliography Index Photographic Section About the Author Credits Copyright About the Publisher PROLOGUE The Mystery of Michelle Obama’s Roots F REEDOM CAME TO JONESBORO, GEORGIA, IN THAT SPRING of 1865, during those hardest of hard times. The town was in ruins, its buildings shattered by cannon fire. The fledgling green fields had been decimated by drought and hunger rippled through the land. Everywhere Southerners turned, people were moving. Many newly freed slaves were dropping their hoes and packing their sparse belongings. They were walking away from the parched earth and the white people who had owned them, overseen them, or marginalized them. Melvinia, a dark-eyed young woman with thick wavy hair and cocoa-colored skin, watched them go. Like all of them, she knew the miseries of slavery. She had toiled in bondage for most of her existence. She had been torn away from her family and friends when she was a little girl. She had been impregnated by a white man when she was as young as fourteen. Yet when the Civil War ended, when she could finally savor her own liberty, she decided to stay. She decided to build a new life right where she was, on the outskirts of that devastated town, on a farm near the white man who had fathered her firstborn son. She was barely in her twenties and silenced by the forced illiteracy of slavery. Even if she had wanted to, she could not have put pen to paper to reveal the name of the father of her child, to spell it out in the permanence of black ink. This was a different kind of affirmation. Her choice was her clue. A census taker would record her address after the war, memorializing her decision in his curly script. His notes would serve as something of a handwritten message that would survive, untouched, for more than one hundred years. It would be the only message Melvinia would ever leave. Nearly a decade would pass before she gathered up her children and headed north on her own. Black people walked then, sometimes for miles and miles on those dusty, country roads, or squeezed onto the crowded, rattling railroad cars that chugged between small towns in rural, up-country Georgia. Sometime in the 1870s, Melvinia put some sixty miles between herself and her past. And somewhere along the way, she decided to keep the truth about her son’s heritage to herself. People who knew her say she never talked about her time in slavery or about the white man who so profoundly shaped her formative years as a teenager and a young mother. She never discussed who he was or what happened between them, whether she was a victim of his brutality or a mistress he treated affectionately or whether she loved and was loved in return. She went her way and he went his, and, just like that, their family split right down the middle. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren—some black, some white, and some in between—scattered across the country as the decades passed, separated by the color line and the family’s fierce determination to step beyond its painful roots in slavery. Contemporary America emerged from that multiracial stew, a nation peopled by the heirs of that agonizing time who struggled and strived with precious little knowledge of their own origins. Melvinia’s descendants would soar to unprecedented heights, climbing from slavery to the pinnacle of American power in five generations. Her great-great-great-granddaughter, Michelle Obama, would become the nation’s first African American First Lady. Yet Mrs. Obama would take that momentous step without knowing Melvinia’s name or the identity of the white man who was her great-great-great-grandfather. For more than a century, Melvinia’s secret held. On November 4, 2008, some 143 years after Melvinia experienced her first days of freedom in that postwar wasteland, Mrs. Obama stood before a crowd of thousands of roaring, singing, and weeping supporters in Chicago’s Grant Park. It was Election Night and her husband had just become the first African American president of the United States. Mrs. Obama was all warm smiles and gracious thank-yous that evening, the poised picture of a sophisticated, self- assured woman prepared to take her place in history. The truth was, though, that she knew very little about her own. The story of her husband’s origins had become the powerful narrative that dominated the 2008 presidential campaign. The son of a white woman from Kansas and a black man from Kenya, Barack Obama embodied the hopes of many Americans eager to see an often-divided nation finally come together to fulfill its egalitarian ideals and step beyond its stains of inequality, segregation, and slavery. Mrs. Obama’s smooth, chocolate- brown skin seemed to hold few surprises. She was born on the South Side of Chicago, in a working-class corner of the city’s storied black community, just like her parents. Like many African Americans, her family had moved north during the Great Migration in the first half of the twentieth century. Mrs. Obama knew her grandparents as a girl, but only bits and pieces about the relatives who came before them. She had grown up hearing whispers about white ancestors in her family tree, but no one knew who they were. Melvinia was gone, buried and forgotten, and her name had long since faded from Mrs. Obama’s family memory. The slave girl’s legacy may well have remained hidden were it not for two strangers—one black and one white—who happened to be watching Mrs. Obama on that stage on Election Night. The bloodlines of those two women also extended back to that devastated Georgia town. In the 1850s and 1860s, their ancestors—Melvinia, who was black, and Henry Wells Shields, who was white —lived together on a two-hundred-acre farm near Jonesboro where they picked cotton, raised cattle, and harvested bushels of Indian corn and sweet potatoes. Over time, those two women would begin unraveling their shared history and, in the process, the First Lady’s as well. But that night, they knew none of it. They watched the Obamas as many of us did, as ordinary Americans eager to witness the moment unfolding before them. Jewell Barclay, an eighty-year-old elementary-school crossing guard, clapped and cheered as she watched Mrs. Obama and her husband stride across her television screen. Jewell is a former cafeteria aide who went to work straight out of high school. She is a white-haired widow, an African American grandmother who has lived most of her life on a neat, tree-lined block in Cleveland. Schoolchildren and their mothers called to her by name whenever she walked by —“Miss Barclay! Miss Barclay!”—and Jewell, funny and kindhearted, consoled the troubled and cheered the brokenhearted. She thanked Jesus for living long enough to see this first black president and First Lady who looked so in love. In a small town outside of Atlanta, Joan Tribble, a sixty-five-year-old bookkeeper, was watching, too. Joan is a fiercely independent divorcée with blue-gray eyes and an associate’s degree, who rarely hesitates to speak her mind. She prides herself on her common sense, her pointed wit, and her beloved grandchildren. She didn’t vote for Mr. Obama. “Too young and too inexperienced,” she observed during the presidential campaign. She cast her ballot for his rival, John McCain, but admired Mrs. Obama from afar. “A strong woman,” she said, nodding approvingly. On Election Night, Joan peered through her wire-rimmed glasses as she tap-tapped the remote control, watching as the tableau of the young president-elect, his wife, and their daughters filled her living room. The two grandmothers would have scoffed with disbelief that night if anyone had told them that they might have a personal connection to the new First Lady or to each other. They were strangers, after all, three women separated by geography and politics, class and race. For Joan Tribble and Jewell Barclay, Mrs. Obama might as well have lived in another universe. She was a Harvard- educated lawyer, a former hospital executive who had earned a six-figure salary and owned a stately mansion in Chicago. As First Lady, she would dine at Buckingham Palace with the Queen of England, chat with Stevie Wonder, and lead the Obama administration’s efforts to combat childhood obesity. Her every public move would be watched by the world. Jewell and Joan, on the other hand, lived ordinary lives, far from the spotlight. But in life, even the most familiar roads sometimes twist and swerve unexpectedly. The pieces started falling into place in October 2009, during Mrs. Obama’s first year in the White House, when she finally learned about Melvinia, the mysterious white man who was her great-great-great-grandfather, and their son, Dolphus. A genealogist, Megan Smolenyak, had discovered the connection and the news broke on the front page of the New York Times in an article that I wrote and reported with a colleague. For the first time, Mrs. Obama could identify a slave in her mother’s family. For the first time, she could point to a white ancestor in her family tree. Some of the First Lady’s friends and colleagues wept when they read about Melvinia, envisioning the young girl so many years ago, and wondering whether she was raped, whether she was loved, whether there was any way to know the truth and the identity of the white man who had impregnated her. Mrs. Obama was so moved that she shared the story with relatives and friends during her first Thanksgiving in the White House that year. They dined on roasted turkey and oyster stuffing, macaroni and cheese, and green bean casserole. And Mrs. Obama, the first descendant of slaves to serve as First Lady, handed out copies of her family tree along with some of the documents that we had uncovered: the obituary of Melvinia’s biracial son, Dolphus, and his funeral program, which included a black-and-white photograph of the man himself. There it was, plain as day: the details of her melting pot ancestry, laced with pain and agonizingly unanswered questions. “It was fascinating,” said Maya Soetoro-Ng, the president’s sister, who was there that night as the nation’s most prominent family shared their personal portion of history at the White House, a mansion built, in part, by slaves. A few months later, the First Lady said she was still coming to terms with her newfound knowledge. “We’re still very connected to slavery in a way that is powerful,” Mrs. Obama told reporters over tea and pastries in the Old Family Dining Room in the White House in January 2010. “Finding out that my great-great-great- grandmother was actually a slave . . . that’s my grandfather’s grandmother. That’s not that far away. I could have known that woman. It just—it makes [slavery] real.” Across the country, Jewell Barclay and Joan Tribble were coming to terms with it, too. I tracked them down after my article appeared in the New York Times. I wanted to dig deeper into the First Lady’s history and began searching for the descendants of Melvinia and her owner, Henry Wells Shields, who I hoped might help unlock the doors to Mrs. Obama’s past. As I explored new branches of the First Lady’s family tree, I discovered that Jewell was Melvinia’s great-great-granddaughter and Mrs. Obama’s second cousin once removed. Joan was Henry’s great-great-granddaughter. This, I thought, was a good place to start. I rang Jewell’s doorbell in Cleveland one sunny afternoon in April, armed with a bulging folder full of census records, death certificates, and fading photographs. We sat together at the kitchen table and I walked her through her family line, one ancestor after another, one generation after another, from that slave girl in Georgia to the First Lady in the White House. For a moment, Jewell was speechless. She had never dreamed that she would see a black president in her lifetime, and there I was telling her that she had a cousin in the White House, that she was related to Michelle Obama. “This is something!” she exclaimed. “This is really something!” She had known Melvinia’s son, Dolphus, when she was a girl; he was her great-grandfather. Dolphus was also the First Lady’s great- great-grandfather, but Mrs. Obama had grown up without knowing about him or about Jewell, her long-lost cousin. “Wouldn’t he be so proud?” Jewell marveled, imagining Dolphus’s reaction to the astonishing news. But her delight was tempered by the thought of what might have happened to Melvinia on that farm so many decades ago. She hesitated for a moment when I asked what she thought Melvinia might have experienced. Then she shook her head. “Masters messing with those young black girls,” she said. “That’s what I think happened.” In Atlanta, Joan had to swallow a harder, more difficult truth: that her great- great-grandfather had held the First Lady’s ancestors in bondage. Worse still was the possibility that one of her forebears might have raped Melvinia. To be related to the First Lady would have been something to marvel at; to suspect that that family relationship was born of unspeakable violence was something else altogether. “It’s horrible,” Joan told me when we sat down over a stack of records in the Georgia Archives in Morrow, Georgia, near where her relatives had settled more than a hundred years ago. “You really don’t like to face this kind of thing.” Some of her elderly cousins wanted to keep quiet about the

Description: