Agni, the Vedic ritual of the fire altar PDF

Preview Agni, the Vedic ritual of the fire altar

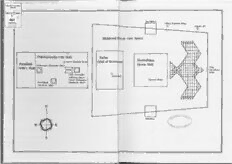

i (&{'6 ~ ; Uppsala Universitets . Bibliotek Sc Depa KBE Ipkfit 824 Agnidhriya Utkara Rubbish Heap O Catvala Pit O I Mahavedi (Great Altar Space) Pracinavamsa (Old Hall) Sadas Havirdhana Q Utkara Rubbish Heap (Hall of Recitation) Patnisala (Soma Hall) Garhapatya (Domestic Altar) Yupa (Wife’s Hall) (Sacrificial o Pole) (Old) Ahavaniya Audumbari ■ (Offering Altar) = (New) Garhapatya Uparava Holes Daksinagni (Domestic Altar) (Southern Altar) Marjaliya J I I ^2'* universitet^^ n AGNI THE VEDIC RITUAL OF THE FIRE ALTAR II Volume Edited by Frits Staal with the assistance of Pamela MacFarland ASIAN HUMANITIES PRESS BERKELEY 1983 Avd. for indologi iranistik och indoeur. sprakforskning This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise, circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being CONTENTS imposed on a subsequent purchaser. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, Preface xi recording or any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Abbreviations xvi Copyright © 1983 by Frits Staal Manufactured in the Republic of Korea PART III by Samhwa Printing Co., Ltd. PERSPECTIVES The Archeological Background to the Agnicayana Ritual, by Romila Thapar 3 r The Pre-Vedic Indian Background of the Srauta Ritual, by Asko Parpola 41 Other Folk’s Fire, by J. C. Heesterman 76 The Geometry of the Vedic Rituals, by A. Seidenberg 95 Ritual Structure, by Frits Staal 127 The Agnicayana Section of the Maitrayani-Samhita with Special Reference to the Manava Srautasutra, by N. Tsuji 135 The Atiratra According to the Kausitaki Brahmana, by E. R. Sreekrishna Sarma 161 Ritual Preparation of the Mahavira and Ukha Pots, by Yasukelkari 168 Agnicayana in the Mimamsa, by K. Balasubrahmanya Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sastri, edited by James A. Santucci 178 Staal, Frits. Srauta Traditions in Recent Times, by C. G. Kashikar and Asko Agni, the Vedic ritual of the fire altar. Parpola 199 Bibliography: p. 703 Recent Nambudiri Performances of Agnistoma and Agnicayana, Includes indexes. 1. Agnicayana ( Vedic rite) I. Somayajipad, by C. V. Somayajipad, M. Itti Ravi Nambudiri, and C. V. (Cherumukku Vaidikan) II. Itti Ravi Erkkara Raman Nambudiri 252 Nambudiri, M. III. De Menil, Adelaide. IV. Title. BL1226.82.A33S7 294.5'38 81-13637 A History of the Nambudiri Community of Kerala, by M. G. S. ISBN 0-89581-450-1 (set) AACR2 Narayanan and Kesavan Veluthat 256 v PART V The Nambudiri Ritual Tradition with Special Reference to the Kollengode Archives, by M. R. Raghava Varier 279 FILMS, TAPES, AND CASSETTES Sanskrit and Malayalam References from Kerala, by K. by Frits Staal Kunjunni Raja 300 The Music of Nambudiri Unexpressed Chant (aniruktagana), by W ayne Howard 311 I. The Films 739 The Five-Tipped Bird, the Square Bird, and the Many-Faced II. The Tapes 744 Domestic Altar, by C. V. Somayajipad, M. Itti Ravi III. The Cassettes 748 Nambudiri, and Frits Staal 343 Contributors 761 Vedic Madras, by Frits Staal 359 Glossary and Index of Terms 769 Notes on Comparison of Vedic Mudras with Madras used in Kutiyattam and Kathakali, by Clifford R. Jones 380 Index of Names 800 Agni Offerings in Java and Bali, by C. Hooykaas 382 Index of Texts 812 Tibetan Homa Rites, by Tadeusz Skorupski 403 Homa in East Asia, by Michel Strickmann 418 The Agnicayana Project, by Frits Staal 456 PART IV TEXTS AND TRANSLATIONS r Baudhayana Srautasutra on the Agnicayana, text by W. Caland, translation by Yasuke Ikari and Harold Arnold 478 Kausitaki Brahmana on the Atiratra, translation by E. R. Sreekrishna Sarma 676 Jaiminiya Srautasutra on the Agnicayana, with Bhavatrata’s Commentary, by Asko Parpola 700 vi Vll PLATES ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT All photographs are by Adelaide deMenil unless otherwise noted. iA-D Vessel Excavated at the Site of Itgi and Identified Fig. 1. Construction of a Right Angle 96 as Ukha (Department of History and Archaeology, Fig. 2. The Basic Bird Altar 97 Karnatak University) 24 Fig. 3. Variant of the Basic Bird Altar 97 2 The Mount at Kausambi Showing the Defence Structures Fig. 4. “The Cord Stretched in the Diagonal ...” 98 (Photo Professor G. R. Sharma) 28 Fig. 5. Squaring the Oblong 99 3A Part of the “Syenaciti” (Professor G. R. Sharma) 30 Fig. 6. Constructions of the Mahavedi 107 3B Section Across the “Syenaciti” (Professor G. R. Sharma) 30 Fig. 7. Construction of a Triangle of Area 7 1/2 Square Purusas 109 4A Another View of the “Syenaciti” (Professor G. R. Sharma) 32 Fig. 8. Troughs According to Baudhayana and Apastamba 110 4B Another Section Across the “Syenaciti” {Professor G. Fig. 9. Circulature of the Square 111 R. Sharma) 32 Fig. 10. The Gnomon 112 5A-B The Tortorise-shaped and Square Tanks at Fig. 11. The Garhapatya and New Garhapatya 116 Nagarjunakonda {Archaeological Survey of India) 36 Fig. 12, Subtracting a Square from a Square 117 6 Altar Excavated at Jagatgram {Archaeological Survey Fig. 13. The “Figure of the Cord” 118 of India) 38 Fig. 14. Construction of a Square of Area n 121 7A Bull and Priestess from Chanhu-Daro {From E. J. H. Fig. 15. Shapes of Bricks of the Five-Tipped Bird 344 Mackay, Chanhu-Daro Excavations 1935-36, New Haven, Conn., 1943, Plate 51, no. 13) 58 Fig. 16. First Layer of the Five-Tipped Bird 346 Fig. 17. Second Layer of the Five-Tipped Bird 347 7B Priest Kneeling before Human Head {From E. J. H. Fig. 18. Third Layer of the Five-Tipped Bird 348 Mackay, Further Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro, II, Delhi 1938, Plate 99A) 58 Fig. 19. Fourth Layer of the Five-Tipped Bird 349 Fig. 20. Fifth Layer of the Five-Tipped Bird 350 8 Yama: One of the Drag gsed or Eight Fearful Ones {2' 10 112" X P 11" painted scroll, E. M. Scratton Fig. 21. Shapes of Bricks of the Square Bird 351 Fig. 22. First Layer of the Square Bird 353 Collection, Tibetan Slide No. 4, Ashmolean Museum) 60 Fig. 23. Second Layer of the Square Bird 354 9A-F Rgveda Mudras I 366 Fig. 24. Third Layer of the Square Bird 355 10A-F Rgveda Mudras II 368 Fig. 25. Fourth Layer of the Square Bird 356 11A-F Rgveda Mudras III 370 Fig. 26. Fifth Layer of the Square Bird 357 12A-F Samaveda Mudras I {Krishnan Nair Studio, Shoranur) 376 Fig. 27. The Bricks of the Many-Faced Domestic Altar 358 13A-F Samaveda Mudras II {Krishnan Nair Studio, Shoranur) 378 Fig. 28. Homa Hearth for Pacifying Rite 407 14 The Blue Fudo (Acala-vidyaraja) {Shoren-in, Kyoto) 430 15 Inner Homa {Photo Kuo Li-ying) 440 Fig. 29. Homa Hearth for the Rite for Gaining Prosperity 410 Fig. 30. Homa Hearth for the Rite for Subjugation 411 16A Reading Out and Burning the Inscribed Tablets {Kuo Li-ying) 448 Fig. 31. Homa Hearth for the Rite for Destroying 412 16B Homa to Dakin! in Fox-Spirit Form {Kuo Li-ying) 448 17 Yamabushi Perform the Saito Goma {Kuo Li-ying) 450 Fig. 32. Placement of Microphones for the Sound Recordings 745 18A-B Nambudiri Visitors 460 19 Helper Dissuading Policeman 466 20 Visitors North of the Sacred Enclosure 470 21 Crowds during the Final Days 472 22 Nambudiri Cameraman After Flow of Wealth 740 23 The Nagra Tape Recorders 746 vm IX PREFACE MAPS Map A. Harappan and Vedic Sites and Excavations xviii The 1975 performance of the Atiratra-Agnicayana called attention to a ritual created in India almost three thousand years ago. The first volume of Maps B. 1-4 §rauta Traditions Agni sought to document and help preserve this ancient tradition. The 1. India 193 2. Maharasthra and Karnatak 194 ceremonies were described and depicted in explicit detail because of their 3- Andhra 195 intrinsic cultural value, because they provide the source material for many 3A. Godavari, Krishna, and Guntur 196 developments in Indian religion, and also because they can be used to con¬ Kerala and Tamil Nadu 197 firm, revise, or reject general theories of ritual and religion. 4- 4A. Central Kerala 198 This second volume of Agni probes more deeply into the authenticity 4B. Thanjavur and Tirucchirappalli 198 of the Nambudiri Vedic tradition and seeks at the same time to explain how such a survival could occur. It shows that much is in fact known about the background, context, and history of the tradition, though some of this information is circumstantial and much of it is difficult of access. As a result EXHIBIT of these investigations, the history of the religions of India now appears in a new light: though Vedic beliefs and doctrines have disappeared or been transformed, Vedic practice has in fact continued. This is significant especial¬ Two Methods for Folding Banana Leaf Inside Back Cover ly in India, where practice—karman—has always been more important than theory. The truth has escaped Indologists who confine themselves to texts and doctrines, and anthropologists who merely scratch the surface. It has been further obscured by the popularization of artificial distinctions like that between so-called Great and Little Traditions. The second volume begins with Part III, “Perspectives,” a series of con¬ tributions by scholars who elucidate the ritual, its background, and its many dimensions. Part IV, “Texts and Translations,” provides sections from ritual manuals of the three Vedic schools represented in the 1975 performance. Part V is concerned with the audiovisual documentation of the Agni ceremony. Part III opens with historical studies by Thapar, Parpola, Heesterman, and Seidenberg. The perspectives adopted in these speculations are diverse; together they remind us of important gaps in our knowledge of early Indian history, and they show us that our widely held assumptions about an Aryan invasion are not only simplistic but also questionable. Staal then analyzes the syntax of the ritual. There follow philological articles primarily con¬ cerned with Sanskrit texts: Tsuji examines a Yajurvedic tradition that differs from that followed in 1975; Sreekrishna Sarma studies the Rgvedic sources underlying the 1975 performance; and Ikari explores a historical link be¬ tween the Agnicayana and the Pravargya ceremony. Balasubrahmanya Sastri illustrates how the Agnicayana has been treated in a later philosophic de¬ velopment. Although the continued existence of grhya rites among the twice-born castes is well known, the survey by Kashikar and Parpola shows how Vedic &rauta traditions, too, are alive in many regions of the Indian subcontinent, the subsequent eight papers focus on the Nambudiri tradition and elucidate xi x PREFACE PREFACE features of Nambudiri Vedic culture. The picture that emerges modifies the of the contributions has been largely retained, a certain amount of standardi¬ common view that Vedic civilization disappeared and was in due course zation has been done, and overlaps have been minimized. Since English is leplaced by Hinduism. What we witness is in fact the continued existence of not the native tongue of most of the authors, nor of the editor, considerations Vedic traditions, though often in remote areas. At the same time, many of style have required much attention. In all these tasks I have been fortunate Indian traditions entered a new phase, which it is customary to call Tantric. in having the assistance of my judicious coeditor, Pamela MacFarland. As This development can be traced in Kerala and among the Nambudiris, but in the case of the first volume, most of the papers have been typed by Ruth its chief impact has been elsewhere. It is not within the scope of this book Suzuki with her customary, yet miraculous, speed. The burden of completing to treat the Tantric fire rites that have proliferated all over India during a variety of smaller tasks was much eased by support from the Department the last two thousand years. However, contributions by Hooykaas, Skorup- of South and Southeast Asian Studies and the Committee on Research of ski, and Strickmann show the extent to which such ceremonies spread over the University of California at Berkeley. large parts of Asia. After depicting a culmination of these Tantric rites in The plates for this volume come from a greater variety of sources the fiery meditations of Japan, Part III ends with an account of mundane than was the case in the first volume. Acknowledgments are due to the De¬ events and practical affairs that pervaded and accompanied the Agnicayana partment of History and Archaeology, Karnatak University (for Plate 1); project. Professor G. R. Sharma (Plates 2-4); the Archaeological Survey of India The texts and translations of Part IV appropriately begin with sections (Plates 5-6); E. J. H. Mackay, Chanhu-Daro Excavations 1935-36 (Plate from the Baudhayana Srautasutra, which is the most detailed and precise 7A); E. J. H. Mackay, Further Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro (Plate 7B); of the sutras, and probably the earliest. The material presented by Ikari and The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Plate 8); Krishnan Nair Studies, Shora- Arnold is the counterpart of the description in Part II, and makes possible nur (Plates 12-13); Shoren-in, Kyoto (Plate 14); Kuo Li-ying (Plates 15-17); a step-for-step comparison of the ritual as it was before 600 b.c. with the 1975 and Adelaide de Menil (Plates 9-11, 18-23). The illustrations in the text performance. The contributions that follow supplement the Yajurvedic data and the numerous maps have again been drawn by Adrienne Morgan with with the Atiratra recitations from the Rgveda and the Agnicayana chants meticulous care. Dr. W. M. Callewaert of the Department of Oriental from the Samaveda. Studies, Leuven, Belgium, has assisted with the map of Andhra Pradesh. The contents of the two volumes reflects a variety of disciplines. The Figures 28-31 are reproduced from The Creation of Mandalas: Rong tha emphasis in Part II may be characterized as anthropological or ethnogra¬ bio bzang dam chos rgya mtsho, Volume 3. phical, it represents Vedic fieldwork. Such fieldwork can be undertaken only The materials presented in this second volume range far in time and by Sanskritists, but all too few have availed themselves of the opportunity. space. Though all are reverberations of Agni and add dimensions to the By contrast, the information provided in Parts III and IV is largely historical Nambudiri Agni, do they place the Nambudiri tradition itself in a new per¬ and philological. Though these contrasting approaches may seem incompa¬ spective, and do they teach us anything else that is new? tible, they are coherent from the Nambudiri, or indeed from the Indian, It would be tempting to claim that this extremely ancient tradition ad¬ point of view. It is not surprising, therefore, that the descriptions offered in mirably fills the gap between the great literary traditions of mankind and Parts II and IV are often extremely similar in spite of their different orien¬ many surviving traditions in preliterate societies that are now beginning to tation. Both descriptions differ in points of detail, but they exhibit the same be studied. Attractive as this speculation is, I shall descend to a less lofty level structure and spirit. If the Nambudiris conceive of the ritual in the manner of conjecture that is still replete with general questions. For example, how of the authors of the ancient manuals, it is not because they imitate the different is the Vedic religion of the Nambudiris from the original Vedic manuals; it is because they embody the same tradition. religion? How do Vedic and Hindu elements blend, mingle, or coexist in the Part V of the second volume gives brief surveys of the twenty hours of Nambudiri tradition? And what light does this throw on the concepts of film footage and the eighty hours of recordings with which we returned tradition and religion? from India. The forty-five-minute film Altar of Fire, edited from these materi¬ When answering the first question, one might begin with the stark als, presents primarily the Nambudiri point of view: it consists of a succes¬ contrast that becomes immediately apparent from a comparison of the sion of episodes suggested by Cherumukku Vaidikan. The contents of the section on Vedic nomads with that on the Nambudiri tradition in the first cassette tapes that accompany this book are described in the third section of volume. While the Vedic nomads were aliens migrating into a new Part V. country where they came in contact with the remnants of an unfamiliar Collecting contributions from an international group of scholars has civilization, the Nambudiris are settled villagers and established country been challenging, time-consuming, and rewarding. Though the original style gentlemen occupying the highest ranks in their caste society. The Vedic Xll Xlll PREFACE PREFACE religion, however, has remained the same in at least one respect. Agni is the example, is not a sacred book: its power lies in mantra, and mantra is vidhi, same fire reinforced by mantras and oblations whose name continues to be that is, an injunction to karman: “Speaking, it is of karman that they speak; familiar from chants and recitations. Agni is not a deity like Siva, Visnu, or and praising, it is karman that they praise” (Brhad-Aranyaka-Upanisad Bhagavatl, whose images are installed in temples. The Vedic religion of Agni 3.2.13). and Soma is as nonanthropomorphic in the Nambudiri tradition as it was The structures of these Asian traditions are related and unrelated to during the Vedic period. One reason for Agni’s continuing identity is this Western patterns of religion, culture, thought, and society in a myriad ways. nonanthropomorphism, which makes it possible for him or it to be carried The term religion, however, has been applied in a clear and helpful manner in an earthen pot. It is in the nature of things that men and anthropomorphic only to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. It is of limited applicability to deities are more readily susceptible to change than such nonanthropomor¬ Buddhism and to the bhakti cults of Saivism and Visnuism. Elsewhere it leads phic substances as Agni. to a meaningless proliferation of problems. In the only intelligible sense of How then are Vedic and Hindu elements related in the Nambudiri tra¬ the term, there are no indigenous religions in India. dition? What students of religion in the West yearn for, of course, is Integra¬ tion. When we ask the performers ‘“Are you Vedic Indians or Hindus?” the answer is “We are Vaidika Nambudiris.” From this we might conclude San Francisco Frits Staal that things that seem to be incompatible to us are harmoniously One in the mysterious orient. But let us not get entangled too soon in our own confu¬ sions. To understand the Nambudiri answer adequately we have to move to a more sophisticated level of conceptual analysis. To begin with, we have to question those rubrics of religion we have come to use with such facile abandon. The labeling of elements as “Vedic” or “Hindu” may reflect a his¬ torical perspective, but it throws scant light on the synchronic relations be¬ tween these elements, and has nothing to do with religion. The same holds for the Harappan and Indo-European features of the Agnicayana itself, where such labeling is even more obviously historical. All such labels are imposed by scholars, laymen, and other outsiders. Their value lies in his¬ torical and comparative analysis; but we use them at our peril when we forget that they are inherently artificial. The concept of religion is a Western concept, and though its origin is Roman, it has been colored by its age-long associations with the monothe¬ isms of the West. Western religion is pervaded by the notion of exclusive truth, and it claims a monopoly on truth. It is professed by “People of the Book,” in the apt phrase the Koran uses to refer to Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Scholars and laymen persist in searching for such religions in Asia. In order to identify them, they seize upon labels from indigenous categories^ rent from their original contexts. Thus there arises a host of religions: Vedic,’ Brahmanical, Hindu, Buddhist, Bonpo, Tantric, Taoist, Confucian, Shinto, etc. In India, and in Asia generally, such groupings are not only uninterest¬ ing but uninformative and tinged with the unreal. What counts instead are ancestors and teachers—hence lineages, traditions, affiliations, cults, eligi¬ bility, initiation, and injunction—concepts with ritual rather than ’truth- functional overtones. These notions do not pertain to questions of truth, but to practical questions: What should the followers of a tradition do? This is precisely what makes such notions pertain to the domain of karman. Hence orthopraxy, not orthodoxy, is the operative concept in India. The Veda, for xiv xv ABBREVIATIONS SV Samaveda Samhita SB Satapatha Brahmana AA Aitareya Aranyaka SGS Sanlchayana Grhya Sutra AB Aitareya Brahmana sss Sanlchayana Srauta Sutra AG (Jaiminlya) Aranyageyagana TA Taittiriya Aranyaka ApGS Apastamba Grhya Sutra TB Taittiriya Brahmana ApSS Apastamba Srauta Sutra TS Taittiriya Samhita ApSulvaS Apastamba Sulva Sutra TU Taittiriya Upanisad AGS Asvalayana Grhya Sutra VaikhSS Vaikhanasa Srauta Sutra ASS Asvalayana Srauta Sutra r VaitSS Vaitana Srauta Sutra AV Atharvaveda Samhita VarSS Varaha Srauta Sutra BAU Brhad Aranyaka Upanisad VS (K/M) Vajasaneyi Samhita (Kanva/Madhyandina) BGS Baudhayana Grhya Sutra VSS Vadhula Srauta Sutra r BharSS Bharadvaja Srauta Sutra BSS Baudhayana Srauta Sutra BSulvaS Baudhayana Sulva Sutra cu Chandogya Upanisad GG (Jaiminlya) Gramageyagana GobhGS Gobhila Grhya Sutra HirGS Hiranyakesi Grhya Sutra HirSS Hiranyakesi Srauta Sutra JA Jaiminlya Arcika JB Jaiminlya Brahmana r JSS Jaiminlya Srauta Sutra KapS Kapisthala Samhita KSS ICatyayana Srauta Sutra KSulvaS Katyayana Sulva Sutra KB Kausltaki Brahmana KhadGS Khadira Grhya Sutra KS Kathaka Samhita KU Kena Upanisad LSS Latyayana Srauta Sutra ManSS Manava Srauta Sutra MS MaitrayanI Samhita MU Maitrayanlya Upanisad ParGS Paraskara Grhya Sutra PB Pancavimsa Brahmana RV Rgveda Samhita xvi XVII PART III PERSPECTIVES