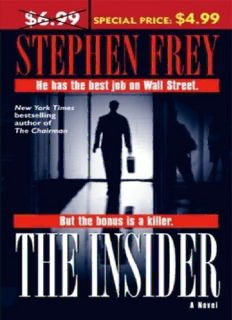

The Insider PDF

Preview The Insider

THE INSIDER Stephen Frey BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK Once again, to my wife, Lillian, and our daughters, Christina and Ashley, who make every day special for me PROLOGUE AUGUST 1994 Like distant headlights, pale yellow eyes burned the water’s surface, reflecting in the beam of the high-powered spotlight that cut through the Louisiana night. Moths swarmed about the bulb while the man held the spotlight aloft with one hand and guided his Boston Whaler over the murky depths with the other. He smiled, satisfied at the number of eyes dotting the surface. He knew alligators as long as fourteen feet lurked beneath—apex-of the-food-chain predators capable of ripping apart a human in the blink of an eye. He wiped away beads of perspiration dripping down his forehead with a red bandanna. It was August, and even at two o’clock in the morning the heat and humidity of Bayou Lafourche were stifling. A large moth landed on his upper lip. He grabbed the insect, crushed it, and tossed its fluttering carcass to the water. Almost instantly something rose from the depths and inhaled the moth in a swirl of black water. The man was momentarily distracted, and the Whaler’s fiberglass bow struck a thick tree stump almost submerged by the high tide. The impact, though not violent, still caused him to pitch forward. The outboard engine, which had propelled the sleek craft across the bay to Bayou Lafourche from Henry’s Landing on the docks of the tiny shrimping town of Lafitte, stalled. He caught himself on the chrome steering wheel, cursed, refired the Mercury engine, once more aimed the spotlight on the water ahead, and proceeded slowly, guiding the boat around the stump. The brackish channel, which a quarter mile back had narrowed to only twenty feet, widened again, making his progress easier. He flashed the spotlight on the muddy bank, then up into the cypress limbs looming over him. They were draped by thick Spanish moss, silky spider-webs ten feet across, and an occasional water moccasin lying in wait to ambush a bird or a rodent. Behind the trees were marshy fields and desolate swamps, all crisscrossed by an intricate labyrinth of waterways. Other than a few energy-industry employees and fishermen, humans rarely ventured this deep into Bayou Lafourche. The only significant inhabitants were alligators and coyotes, which hunted white-tailed deer and nutria—a strange, orange-toothed cross between a rat and a beaver. This was the middle of nowhere, and it was perfect. The boat’s engine stalled again as water lilies thickened on the surface and wrapped around the Whaler’s propeller, ensnaring it like a boa constricting about its prey. The man turned off the spotlight and for several seconds stood behind the steering console, listening. Without the constant throb of the engine, Bayou Lafourche was deathly still save for the groggy symphony of frog and insect calls and the gentle lap of water against the boat’s smooth hull. He glanced toward a hazy, moonless sky, then back over his shoulder toward New Orleans. The city was only fifty miles away, but it might as well have been five hundred, so desolate was this place. “Hello.” The man’s head snapped to the right and he flicked the spotlight back on, aiming it in the direction from which the voice had come. Paddling toward him was a thin, elderly man sitting in the aft seat of a battered metal canoe, a grizzled hound standing like an oversized hood ornament in the bow. The dog was wagging its tail excitedly and panting in the oppressive heat, its pink tongue dangling obscenely from glossy black jaws. “I thought I was the only person within ten miles of here,” the elderly man called out in the odd drawl of his singsong Cajun accent. As he pulled alongside the Boston Whaler, he shielded his eyes against the spotlight’s fierce glare. “Name’s Neville,” he announced, exhibiting two rows of crooked, coffee-stained teeth beneath the brim of a soiled Mack Truck cap. “This here’s Bailey.” Neville pointed at the sad-eyed hound, which had placed its front paws on the gunwale of the man’s boat. The dog was sniffing intently, fixated on a large canvas sack lying in the Whaler’s bow. “What the hell are you doing out here this time of night?” he asked. “I’m an inspector with Atlantic Energy.” The man scrutinized Neville’s weather-beaten face for signs that this was anything but a random encounter. “Just checking gauges on the wellheads.” Neville removed his cap and scratched his bald head. “I don’t remember Atlantic having no rigs out in this part of Lafourche.” He replaced the cap on his bare scalp, then dug into a crusty leather pouch attached to his belt, removed a dark, leafy wad of chewing tobacco, and stuffed it between his cheek and gum. “And I ain’t never met no energy-company inspector out here at this time of night. Even the state fish-and-game boys are in bed by now.” “There’s always a first for everything,” the man replied tersely. He had noticed Neville subtly eyeing the canvas sack as well as the .30-06 Remington rifle and the cinder blocks lying next to it. “Mmm.” Neville glanced at Bailey. “Easy, pup,” he said gently. The dog was agitated, whining and wagging its tail furiously. “Quite a rifle you got there, mister.” “I never come out here without firepower. You can’t be too careful this deep in Lafourche.” “I guess so,” Neville agreed. “Christ, that thing would bring down a charging bull elephant with one shot. You wouldn’t have any problem at all stopping an alligator with it. Not even them big territorial males.” “That’s why I’ve got it.” The man was impatient to be on the move, but first he needed information. “What are you doing out here this late?” “Checking my nutria traps,” Neville replied defensively. On top of a large red cooler positioned between Neville’s knees lay a revolver, what looked like a Ruger.44 Magnum. The odds were excellent that Neville was really hunting alligators, which was illegal until September and probably why he was paddling through Bayou Lafourche in the dead of night. “You live out here?” the stranger asked. “Yeah,” Neville said warily, checking the hunting rifle in the bow of the Whaler once more. He spat tobacco juice over the side. Instantly it spread out like a drop of oil hitting the water. “Why?” “I assume when September gets here you’ll be hunting alligators.” The man knew that Neville could earn a significant amount of money selling the valuable skins and meat to black-market buyers on the docks of Lafitte— buyers who didn’t care that the strictly controlled and hard-to-obtain state game-and-wildlife tags weren’t impaled in the alligator tails. “I’m out here on a regular basis and I’ve seen quite a few giants. Gators that would bring a nice price in Lafitte. Several were over twelve feet, and I’ve seen them in the same places over and over.” “Oh?” Neville tried not to sound interested. But one twelve-foot alligator could bring him almost three hundred dollars cash at the docks in town, close to what he earned in a week as a deckhand on the shrimping boats. “Where were they?” The man shook his head. “I’d have to draw you a map. You’d never find the spots without it.” He picked at his cuticles for a few seconds, then looked up slowly. “I could come by your camp sometime if you tell me where it is.” Neville was uncomfortable giving away the location of his home, but he wanted that information about the large alligators. “Twelve feet, huh?” “Yeah. And I’d be grateful if you got them. I don’t like those big ones swimming around out here while I’m trying to check gauges.” After a few moments Neville nodded cautiously. “Back down the way you come, then left at the first canal. Up there about two miles in a grove of willows. I got one of the only cabins this side of Lafourche. Now that I think about it, it might be nice to have a little company once in a while.” The man nodded. He had what he needed. “Okay.” He leaned down and gunned the Whaler’s engine in reverse, ridding the propeller of the choking water lilies. Bailey quickly retreated to the canoe. “Adios!” the man yelled above the roar as he powered forward once more and steered away. Twenty minutes later, when the man was certain he had left Neville and his too-curious hound far behind, he cut the engine and dropped anchor. For several moments he aimed the spotlight about the water’s surface and counted ten sets of yellow eyes reflecting in the glare. He moved to the front of the boat, removed a body from the canvas sack, and, with thick chains, affixed the cinder blocks to the body’s neck, wrists, and ankles. He caught his breath for a moment, then, with a herculean effort, rolled everything over the side of the boat. The body and the cinder blocks splashed loudly in rapid succession. By the time the man retrieved the spotlight and aimed it down on the black water, only a few bubbles remained. The alligators would feast that evening. The man turned and headed back to the steering wheel. He was going to take Neville up on his offer to stop by—probably a little sooner than the Cajun had anticipated. Neville wouldn’t see sunrise. The Gulfstream IV climbed off the St. Croix runway into the night, roared over the lights of a sprawling oil refinery, and headed north for a hundred miles out over the Atlantic Ocean. Then it turned west, toward Miami. The mood on board was somber. That afternoon the five senior executives now sitting quietly in the jet’s passenger compartment had made an exhaustive presentation to a wealthy individual living on the island. Several days earlier he had expressed a preliminary interest in their company. The executives needed money desperately and had flown to St. Croix immediately to persuade him to become their partner. For all intents and purposes their company was insolvent, though only a few individuals outside the senior management team knew how dire the situation was. At the conclusion of the presentation the investor had decided against making what was marketed to him as the opportunity of a lifetime. He had sensed desperation seeping through the executives’ conservative suits and too- confident, too-cavalier demeanors. Their answers to his questions were unspecific and evasive, and they had traveled too quickly to see him. An experienced investor, he had learned that people who were overly accommodating usually had pressing needs, and more often than not pressing needs were a precursor to financial distress—something he wanted no part of. Time had run out for the executives. The company didn’t have enough money in its checking account to meet the payroll at the end of the week, no more availability under its bank line of credit, and only a dwindling stream of customer payments trickling in. The next day the chief executive officer would call the lawyers in New York and request that they file the appropriate bankruptcy documents. There were no options left. The CEO gazed out his window into the darkness. The bankruptcy filing would buy time, but little else. Without a significant slug of fresh capital, the company was doomed. Ultimately it would be liquidated for salvage value by creditors who would be lucky to receive fifty cents on the dollar for the assets— a scenario that would net the original equity investor nothing. The CEO shut his eyes tightly, trying not to think about how difficult the telephone call to that man would be. The bomb had been armed moments after takeoff by a wire running from where it had been planted in the baggage compartment to the nose-gear uplock switch. When the wheels had fully retracted into the fuselage, the countdown began automatically, set to expire thirty-two minutes later, when the jet would be over an area of the Atlantic where the seabed was deep and the currents strong. Where all remnants of the plane and its occupants would be lost forever only a few minutes after the crash. Where the emergency locator transmitter would die twenty-four hours later without guiding rescuers or investigators to the sight—if its electronic pulse even survived the explosion. The man scanned the starry sky from the deck of the sailboat, listening intently. He knew the plane should be close, and as the seconds ticked by he worked hard to control his anticipation—and his anxiety. Finally he heard the whine of engines and moments later observed a tiny flash of light when the bomb detonated. Then he saw a larger flash as the jet’s fuel tanks caught fire and exploded, sending the decimated craft plummeting toward the water’s surface in a shower of twisted metal. He let out a long, slow breath. He had executed two extremely sensitive missions in rapid succession. His superiors would be pleased. The cause would live on. CHAPTER 1 JUNE 1999 “How much do you make?” “Salary or total compensation?” Jay West asked deliberately. He never disclosed sensitive information until he absolutely had to, even in a situation like this one, where he was expected to answer every question quickly and completely. “What was the income figure on your W-2 last year? A W-2 is that little form your employer sends you each January to let you know how much you have to report to the IRS.” “I know what a W-2 is,” Jay answered calmly, displaying no outward irritation at the interviewer’s sarcastic tone. The young man on the opposite side of the conference room table wore a dark business suit, as did Jay. However, the other man’s suit was custom-made. It was crisper, was crafted of finer material, and followed the contours of his muscular physique perfectly. Jay had purchased his suit off the rack, and it bunched up in certain spots despite a tailor’s best efforts. “The commercial bank I work for provides me certain fringe benefits that don’t appear on my W-2, so my income is actually more than—” “What kind of fringe benefits?” the interviewer demanded rudely. For a moment Jay studied the unfriendly square-jawed face beneath the strawberry-blond crew cut, trying to determine if the confrontational demeanor was forced or natural. He had heard that Wall Street firms often made prospective employees endure at least one stressful interview during the hiring process just to see how they reacted. But if this guy was acting, he was giving an Academy Award performance. “A below-market mortgage rate, a company match on my 401K plan, and a liberal health insurance package.” The man rolled his eyes. “How much can those things be worth, for Christ’s sake?” “The amount is significant.” The man waved a hand in front of his face impatiently. “Okay, I’ll be generous and add twenty thousand to the figure you quote me. Now, how much did you make last year?” Jay shifted uncomfortably in his seat, aware that the figure wouldn’t impress the investment banker. “Hello, Jay.” Oliver Mason stood in the conference room doorway, smiling pleasantly, a leather-bound portfolio under his arm. “I’m glad you could make time for us tonight.” Jay glanced at Mason and smiled back, relieved that he wasn’t going to have to answer the income question. “Hi, Oliver,” he said confidently, standing up and shaking hands. Oliver always had a sleek look about him, like an expensive sports car that had just been detailed. “Thanks for having me.” “My pleasure.” Oliver sat in the chair next to Jay’s and put his portfolio down. He gestured across the table at Carter Bullock. “Has my lieutenant been grilling you?” “Not at all,” Jay answered, trying to seem unaffected by Bullock’s third degree. “We were just having a friendly chat.” “You’re lying. Nobody ever just chats with Bullock during an interview.” Oliver removed two copies of Jay’s resume from the portfolio. “Bullock’s about as friendly as a honey badger, which is what he’s affectionately known as around here,” Oliver explained. “Badger, for short.” He slid one copy of the resume across the polished tabletop. “Here you go, Badger. Sorry I didn’t get this to you sooner. But I’m the captain and you’re just a deckhand on this ship, so deal with it.” “Screw you, Oliver.” Bullock grabbed the resume with his thick fingers, scanned it quickly, then groaned, crumpled the paper into a ball, and threw it toward a trash can in a far corner of the conference room. “Do you know about honey badgers, Jay?” Oliver asked in his naturally aloof, nasal voice. He was smiling broadly, unconcerned by Bullock’s less-than- positive reaction to Jay’s resume. Jay shook his head, trying to ignore the sight of his life being tossed toward the circular file. “No.” “Most predators aim for the throat when they attack their prey.” Oliver chuckled. “Honey badgers aim for the groin. They lock their jaws and don’t let go, no matter what the prey does. They don’t release their grip until the prey goes into shock, which, as you might imagine, doesn’t take long, especially if the prey is the male of the species. Then they tear the animal apart while it’s still alive.” Oliver shivered, picturing the scene. “What a way to go.” “Screw you and your mother, Oliver.” But Bullock was grinning for the first time, obviously pleased with his nickname and his tough-as-tungsten reputation. Oliver put both hands behind his head and interlaced his fingers. “Don’t let me interrupt, Badger.” Bullock leaned over the table, a triumphant expression on his wide, freckled face. “So, Jay, how much did you make last year?”

Description: