Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages; Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico PDF

Preview Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages; Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico

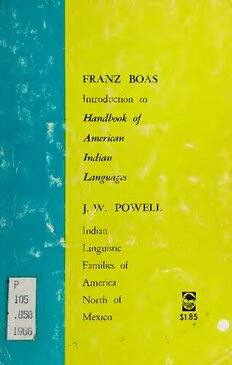

FRANZ BOAS Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages J. W. POWELL Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMASJ. BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY i -jiunAi Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/introductiontohaOOOOboas FRANZ BOAS Introduction to Handbook of American Indian Languages J. W. POWELL Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico Edited by Preston Holder UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS • LINCOLN . ? fib b 85 P/D5 © Copyright 1966 by the University of Nebraska Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 65-19467 First Bison Book printing September, 1966 Second Bison Book printing September, 1968 Third Bison Book printing April, 1970 Fourth Bison Book printing July, 1971 Manufactured in the United States of America Preface This volume contains two fundamental contributions to the study of American Indian languages. Although both bear on the problem of the exact nature of North American native language, they are of quite different intent: Franz Boas, in his Introduction to the Handbook of American Indian Lan¬ guages (1911), is concerned with basic linguistic characteris¬ tics,1 while J. W. Powell, in “Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico” (1891), treats the classification of languages in terms of lexical elements.2 Both works have been relatively difficult of access, yet both are of immediate and continuing value, not only to students of linguistics but to all Americanists and anthropologists in general. Boas’s essay presents some of his fundamental ideas con¬ cerning language as of the end of the first decade of the present century. Originally intended to lay the groundwork for the series of grammatical sketches presented in the four- volume Handbook of American Indian Languages, it gives a clear statement of fundamental theory and of basic meth¬ odological principles which demonstrate the^ij^d^qM^cyrqf ,jA. 'W (v) PREFACE the old methods and point to new paths of research which were to lead to impressive results. In later essays—his Intro¬ duction to the International Journal of American Linguistics (1917), “The Classification of American Languages” (1920), and “Classification of American Indian Languages” (1929)3— Boas presented further ideas concerning the theory and meth¬ ods of linguistic analysis and classification. These essays must be consulted by the student for a thorough understanding of the growth of linguistic studies, but nowhere in them will he find that Boas’s original stand is seriously modified. J. W. Powell’s work following Gallatin’s original efforts, is based on contributions by Horatio Hale, James C. Pilling, George Gibbs, Stephen Powers, Albert S. Gatschet, Stephen R. Riggs, J. Owen Dorsey, and many other ethnologists and linguists associated with the Bureau of American Ethnology during the nineteenth century. The long-continued study of North American native languages seems to have grown out of a central and vexing problem facing the United States government: how to adequately identify, classify, and locate the various indigenous peoples of North America, especially those of the United States and Alaska. Powell explains his methodology in considerable detail. While the weakness of classifying languages on the basis of brief vocabularies is self-evident—its dangers are fully ex¬ plored in Boas’s essays—nonetheless, the linguistic families determined by Powell represent a very real configuration. The passing years have seen some consolidation of originally separate elements, a few changes in orthography, and various additions, but the main outlines remain unchanged. Boas paid a deserved tribute in 1917 when he said that “the classi¬ fication of North American languages, that we owe to Major Powell, . . . will form the basis of all future work. . . .”4 In a more recent appraisal, Harry Hoijer stated: “Though a number of far-reaching modifications of this classification have been suggested since, the groups set up by Powell still retain their validity. In no case has a stock established by Powell been discredited by later work; the modifications that have been suggested are all concerned with the establishment (vi) PREFACE of larger stocks to include two or more of Powell’s groupings.5 Thus Powell’s fifty-eight families are reduced to fifty-four in Hoijer’s listing. In the present volume, modern spellings are indicated by listing Hoijer’s labels in a table following the text. The student will find that many of the ethnological and linguistic generalizations in Powell’s preliminary discussion are no longer tenable. That we are able today to criticize and discard these generalizations is a measure of the growth of our field and the increase in our understanding of the complexities of cultural processes. The past two decades have seen great interest in the problems of classification raised by these lists, especially concerning relationships suggested by Edward Sapir at the super-family, stock, and phylum levels.6 The development of lexicostatistics and glottochronology under Swadesh’s lead¬ ership has led to suggestions of relationships far beyond the level of the family and at the same time has given some indi¬ cation of the time intervals involved in the differentiation of the languages within families. The student must familiar¬ ize himself with this extensive literature if he is to under¬ stand the current direction of research in this field.7 Again it must be stressed that all of this later work stems directly out of the pioneering'papers here presented. Preston Holder University of Nebraska 1. Franz Boas, Introduction, Handbook of American Indian Lan¬ guages, Bulletin 40, Part I, Bureau of American Ethnology (Washing¬ ton, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), pp. 1-83. 2. J. W. Powell, “Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico,” Seventh Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1891), pp. 1-142. 3. All are reprinted in Franz Boas, Race, Language and Culture (New York: Macmillan, 1940). 4. Franz Boas, Introduction, International Journal of American Lin¬ guistics, in Race, Language and Culture, p. 202. 5. Harry Hoijer, Introduction, “Linguistic Structures of Native North America,” Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology No. 6, ed. C. Osgood (New York, 1956), p. 10. PREFACE 6. Sapir’s original presentation, updated by Hoijer in recent printings, is to be found in the 14th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica under “Central and North American Languages,’’ Vol. V, pp. 138-141. The table of relationships gives some idea of the suggested changes: Proposed Classification of American Indian Languages North of Mexico (and Certain Languages of Mexico and Central America) 1. Eskimo-Aleut II. Algonkin-Wakashan A. Algonkin-Ritwan B. Kootenay 1. Algonkin C. Mosan (Wakashan-Salish) 2. Beothuk 1. Wakashan (Kwakiutl- 3. Ritwan Nootka) a. Wiyot 2. Chimakuan b. Yurok 3. Salish III. Nadene A. Haida B. Continental Nadene 1. Tlingit 2. Athapaskan IV. Penutian A. Californian Penutian C. Chinook 1. Miwok-Costanoan D. Tsimshian 2. Yokuts E. Plateau Penutian 3. Maidu 1. Sahaptin 4. Wintun 2. Waiilatpuan (Molala- B. Oregon Penutian Cayuse) 1. Takelma 3. Lutuami (Klamath- 2. Coast Oregon Penutian Modoc) a. Coos F. Mexican Penutian b. Siuslaw 1. Mixe-Zoque c. Yakonan 2. Huave 3. Kalapuya V. Hokan-Siouan A. Hokan-Coahuiltecan b. Coahuilteco 1. Hokan (1) Coahuilteco a. Northern Hokan proper f Karok (2) Cotoname -i (1) Chimariko (3) Comecrudo [ Shasta-Achomawai c. Karankawa (2) Yana B. Yuki (3) Pomo C. Keres b. Washo D. Tunican c. Esselen-Yuman 1. Tunica-Atakapa (1) Esselen 2. Chitimacha (viii)