Creative Quest PDF

Preview Creative Quest

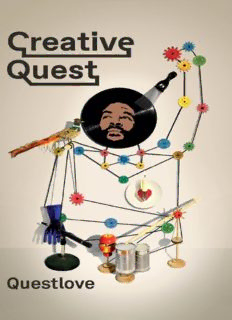

Photo courtesy of the author Dedication To my father, my first mentor. Thank you for teaching me how to be creative, how to be focused, how to be resilient—how to be. Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Introduction The Spark Mentors and (Apprentices) Getting Started . . . The Network Reduce Reuse Recycle Curation as Cure The Departure The Market Success and Failure No End Afterword Acknowledgments A Note on the Cover Index About the Authors Copyright About the Publisher Introduction D ecades into my career, with many albums and songs under my belt, I still don’t know if I am truly creative. Most days I spend more time absorbing the creative work around me than actually creating myself. At times I feel like I’m a way better student than I am a teacher or a maker. The most creative thing I did today, for example, was waking up and texting Jimmy Jam about an obscure B- side from 1987. But this isn’t a bad thing; I feel like my life is complete because I’m only a text away from a lot of the artists in my childhood record collection. That leaves me almost as fulfilled as if I’d created the work myself. That’s how many days go: I wake up, I engage with creative work, I don’t create anything myself. Sometimes I think I’m restrained by information—that I’m too focused on the finer points of things, too detail-minded, unable to free myself from the hold of other people’s work. Is it more important for me to make a song that impacts the world or do I feel satisfied learning about someone else’s songs (or books or movies)? Other days, though, I create plenty: I make albums or participate in comedy skits or learn how to make housewares or write books. So am I creative? Can I teach other people to harness their own creative energies and to get past some of their own creative anxieties? This book is a way to resolve these questions, and it’s also a way to leave those questions unresolved. I will explore my creative process by examining the creative processes of people I know—who are already committed artists, whether musicians or chefs or comedians or directors. I will play good student to their good teacher, and I will try to understand the ways they feed my own creativity. I will also tell stories from my own life. These stories are not always new, but in the retelling, they serve a different purpose. When I told stories in my memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues, it was to guide the reader through the corridors of my life. When I sometimes tell stories from my drumset on The Tonight Show, it’s to get a laugh out of Jimmy or lead into the next segment. In this book, the stories are commentaries on themselves, opportunities to present and analyze the creative process. Think of them as a remix. Do creative people just make things without thinking about them? Do they worry about not getting it right, or being told that they’re not getting it right, or do they just walk into the room, take the paint and canvas, and go to work? I’m asking because I have never been able to set aside that self-consciousness. Because of that, I have long been interested in books about creativity. Or rather, I’ve been interested by why I’m skeptical of them. I buy them and read them and then think about whether or not they contribute to my overall sense of things: specifically, how ideas move from my brain out into the world. More often than not, they don’t. It’s not a criticism of the books, necessarily. Many of them are books that other people swear by—they tell me to get them and assure me that they’ll change my life. When they don’t, I’m always a little bit deflated. What I’ve learned is that my approach to creativity is unlike most other people’s. I don’t know if it’s better or worse, but I know that it’s different, largely because my experience has pulled me through all these disparate disciplines, sometimes without much advance preparation. Books about creativity, at least before this one, tend to fall into two broad categories. On the one hand, there are books that treat creativity from a straightforward how-to stance. How do you make a bestselling record? How do you write a blockbuster screenplay? How can any average citizen tap into their creative instincts? On the other hand, there are books that look at creativity as a therapeutic endeavor. How do you come up with ideas that make you a better and more confident person in your everyday life? I wanted to write a book that does both at the same time. I have worked as a creative professional since I was in my teens, and I feel compelled by each of these capacities: “creative” and “professional.” Art doesn’t have to be something you do only behind closed doors, for personal spiritual gain. But it also isn’t simply a product-based process that’s at the mercy of the market. I live and work at the intersection of art and commerce. I want to show people how I learned to move along two tracks at once—how I kept taking personal risks in my art while at the same time negotiating the ins and outs of commercial success. The result is this book, which is my story of understanding creativity and succeeding in creative endeavors. I want to use my experiences—not only my own successes and failures, but the challenges faced by (and overcome by) others—to help readers plot a course through the creative process. Everyone knows the broad shape of that process. Everyone knows that it starts with the idea and ends with the execution of that idea, but the quest of the artist is both more general and more specific. You have to know when to leap on an idea and when to leave it alone, when to keep it close to the vest and when to release it into the world, when to consolidate your gains and when to move into uncharted territory. Creativity isn’t Candyland—it’s more complicated than that—but there is a game board, with general principles to follow, and I want to sketch it out for readers. In The Wizard of Oz, after Dorothy has been through the wringer, the Good Witch tells her that she has had the power to go home all along. All she had to do was click the heels of her ruby slippers. I’m not going to Good Witch you guys and make you wait until the end. I’ll tell you this right at the beginning: you—and only you—have the power to make these creative exercises work. All I can do is drop hints, drop bread crumbs, and drop science. Pick up what you want when you want. The book is in your hands. How it gets used is also in your hands. I won’t make grand claims. But I will make this one: if you use this book properly, you’ll learn something, even if what you learn is that you already believed your own versions of many of these insights. That’s one of the secrets that maybe a savvier marketer would save for a bonus track but I’m sequencing first—lots of these things will harmonize with the instincts you already have. I’ll give you supporting evidence. I’ll show you how other people have similar practices, both to each other and to me. Most important, I’ll encourage you to recognize that your suspicions about creativity are probably correct. Getting to the point where you can credit your own intuition is an important part of moving forward creatively. I often think of creativity as functioning in the middle of a stream. Ideas are happening all around me, all the time, and I have had to learn how to process them all. I have learned how to be a filter: informed, active, engaged, and motivated. Whether I’m working on an album, a song, a design, or a conversation, I’ve been lucky enough to cross paths with thought leaders in various fields: from Neil deGrasse Tyson to President Barack Obama, to Tom Sachs to Björk to Ferran Adrià, to David Lynch to Kehinde Wiley to Wangechi Mutu to Usher. These people have inspired me, often with stories about how others inspired them. Each creative person sits at the base of a tree whose branches stretch far and wide—to other fields, back through time—in ways that help to define and redefine their creative process. What follows is a bit of a leap, but creativity always is. So let’s interlock arms, metaphorically speaking, and jump. —Questlove

Description: