Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts PDF

Preview Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts

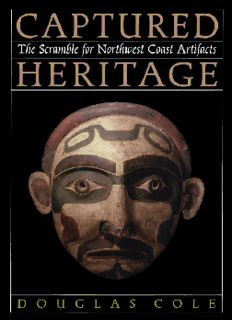

C A P T U R ED HERITAGE C A H E P T U R ED R I T A GE The Scramble, for Northwest Coast Artifacts DOUGLAS COLE U B C P R E S S / V A N C O U V E R 1985 by Douglas Cole Reprinted 1995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper ISBN 0-7748-0537-4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Cole, Douglas, 1938- Captured heritage Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7748-0537-4 1. Indians of North America - Northwest Coast of North America - Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America - Northwest Coast of North America Antiquities — Collectors and collecting. I.Title. E78.N78C64 1995 971.1*100497 C95-910651-0 Zur Erinnerung an ein Marchen This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the ongoing support to its publishing program from the Canada Council, the Province of British Columbia Cultural Services Branch, and the Department of Communications of the Government of Canada. Cover design by George Vaitkunas Text design by Barbara Hodgson Typeset by Alphatext Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens UBC Press University of British Columbia 6344 Memorial Road Vancouver, BCV6T 1Z2 (604) 822-3259 Fax:1-800-668-0821 E-mail: [email protected] Contents Preface to the Reprint vii Introduction xvii One Prelude 1 Two Secretary Baird and Judge Swan Build a Collection 9 Three The French and German Competitors 48 Four The North American Rivals 74 Five Museums, Expositions, and Their Specimens 102 Six The American Museum and Dr. Boas 141 Seven The Field Museum and Dr. Newcombe 165 Eight A Declining Market 212 Nine Successful Collecting in Thin Country 244 Ten Epilogue 280 Eleven Themes and Patterns 286 Notes 312 Index 3 63 This page intentionally left blank Preface to the Reprint ON 3 OCTOBER 1994, the four posts and interior screen of the Whale House — among the greatest treasures of Northwest Coast art and artifact — returned to Kluckwan, Alaska. Sold in 1984 by their family possessors to art dealer Michael Johnson and quietly removed while most residents were off playing bingo, their voyage to New York had been halted in Seattle by an injunction that disputed the right of the sellers to ownership. While the art remained locked away for a decade in a warehouse, the Kluckwan argued about own- ership in American courts.The Whale House treasures were not family- owned but clan-owned, insisted Whale clan members. The legal dis- pute was decided only after the Anchorage federal district court shifted jurisdiction to a new village court that upheld clan owner- ship and had the five pieces returned. This is merely the latest episode in the long saga of the Whale House, whose treasures have been sought by museum collectors for a century. The earlier episodes were touched on in Captured Heritage, published shortly after the Seattle internment (1985, pp. 259-64, 281, 311).1 Captured Heritage is about the Whale Houses that got away, about the flow of artifacts from Kluckwan and hundreds of other North- west Coast villages to museums of the Western world during the great age of anthropological collecting. That current had lost its strength by the 1930s. More recently a counter-current has begun, reversing the flow, if only weakly. Stockholm's museum transferred ownership of a pole to the Haisla in 1994, its repatriation awaiting a suitable venue in Kitimat. The Anglican diocese in Victoria returned five Nishga pieces after protests forced it to reverse its initial decision to sell the artifacts vii Vlll PREFACE to help with cathedral maintenance. The Tsimshian are negotiating •with the National Museum in Ottawa for return of a portion of their artifacts to a suitable home at Port Simpson. American legislation, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, requires the return of human remains and funerary and sacred objects to American Native groups who request them. The implications of this are still unfolding. The Smithsonian Institution, under its own legislative mandate, repatriated war gods to the Pueblo of Zuni, whose" claim was clearer than that most Northwest Coast groups can make for their ceremonial objects. Most notably, the Museum of the American Indian (which figures promi- nently in the later part of this book), taken over now by the Smithsonian and directed by Native American professionals, intends to return significant parts of the collection to the communities from which they came. The returned items will include communally owned property, illegally acquired objects, and duplicate or abundant material. The museum has already agreed to return its identifiable portion of the potlatch-law surrenders to Kwakiutl museums at Cape Mudge and Alert Bay, where they will be reunited with those returned by the Canadian National Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum. These are a few examples of how current opinion, some- times sanctioned by law, gives repatriation strong force. At issue is an ownership that, until recently, went unquestioned. "The very right of old and established museums to the objects in their possession is now contested," wrote an anthropologist in the year that Captured Heritage appeared. "No longer is it possible for museum anthropologists to treat the objects of others without seri- ous consideration of the matter of their rightful ownership or the circumstances of their acquisition."2 Who "owns" a Kwakiutl dance mask? A Haida mortuary pole? A Chilkat dance screen? The muse- um that acquired it? Or the people who made it, invested it with its original purpose and meaning, whose name it still bears in the cata- logue or label of the museum? These are not simple questions but part of the increasingly contested field of ownership. Possession is one thing; "ownership" now quite another. The right to interpret has become an area as contested as the right of ownership. Who should control the exhibition and interpretation of museum artifacts? Is it the "colonizer" or the "colonized," the European curator or the Native people3 represented? Whether at the American Museum in New York, the Rasmussan collection in PREFACE IX Portland, or the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, it is now a standard, even codified, principle that displays must be the result of collaboration between curators and the Natives whose past or present they depict.4 "People have the right to the facts of their own lives."5 If the postcolonial age has affected museums, it has had at least an equal impact upon scholarship. Since the first appearance of Captured Heritage, a great deal has been written on museums and their collec- tions. Some of it advances the history of Northwest Coast collect- ing.6 Most, however, focuses on museums and collecting, often in the postmodern or cultural studies idiom. If postcolonial discourse and Native cultural concerns have eroded the self-confidence of muse- ums, so too has the critical scholarship of postmodernism shaped the discourse about museums. While different cultural critics read anthropological museums in different ways, the trend is to view them as part of a Western pattern, a discourse, that was constructed as part of the process of colonial dominance. The West invented its versions of "primitive" people while appropriating their objects.The nineteenth-century evolution- ary discourse used these to demonstrate racial and cultural superiority. A twentieth-century liberal and relativist discourse tempered the racism but continued to see primitive culture as something that had ceased to exist, or would soon do so. In either case, the image of the "primitive" was an invention, alterable in its uses. The "traditional" and "authentic "American Indian was frozen in the past; postcontact alterations corrupted and destroyed that authenticity. The idea of a pristine, uncontaminated culture served romantic Western primi- tivists seeking an escape from their own industrial modernity. Even more, it served the interests of those who sought control over Native lands and resources. All was within the hegemonic framework of expanding Western capitalism, technology, and modernism. The dis- play of Indian artifacts functioned in a context that communicated power relations — the power and authority of European elites not simply over Natives but also over workers and immigrants. This invention of the primitive Other by Westerners and their museums served not merely to construct stereotypes of Indian cul- tures but, at least as much, to construct a Western identity opposite to all that was Native and primitive. A construction of the Other meant a simultaneous construction of the self. James Clifford describes how anthropological collection and display were crucial processes in

Description: